Arachnofeel...YAAGGHH!!

by Jay Vannini

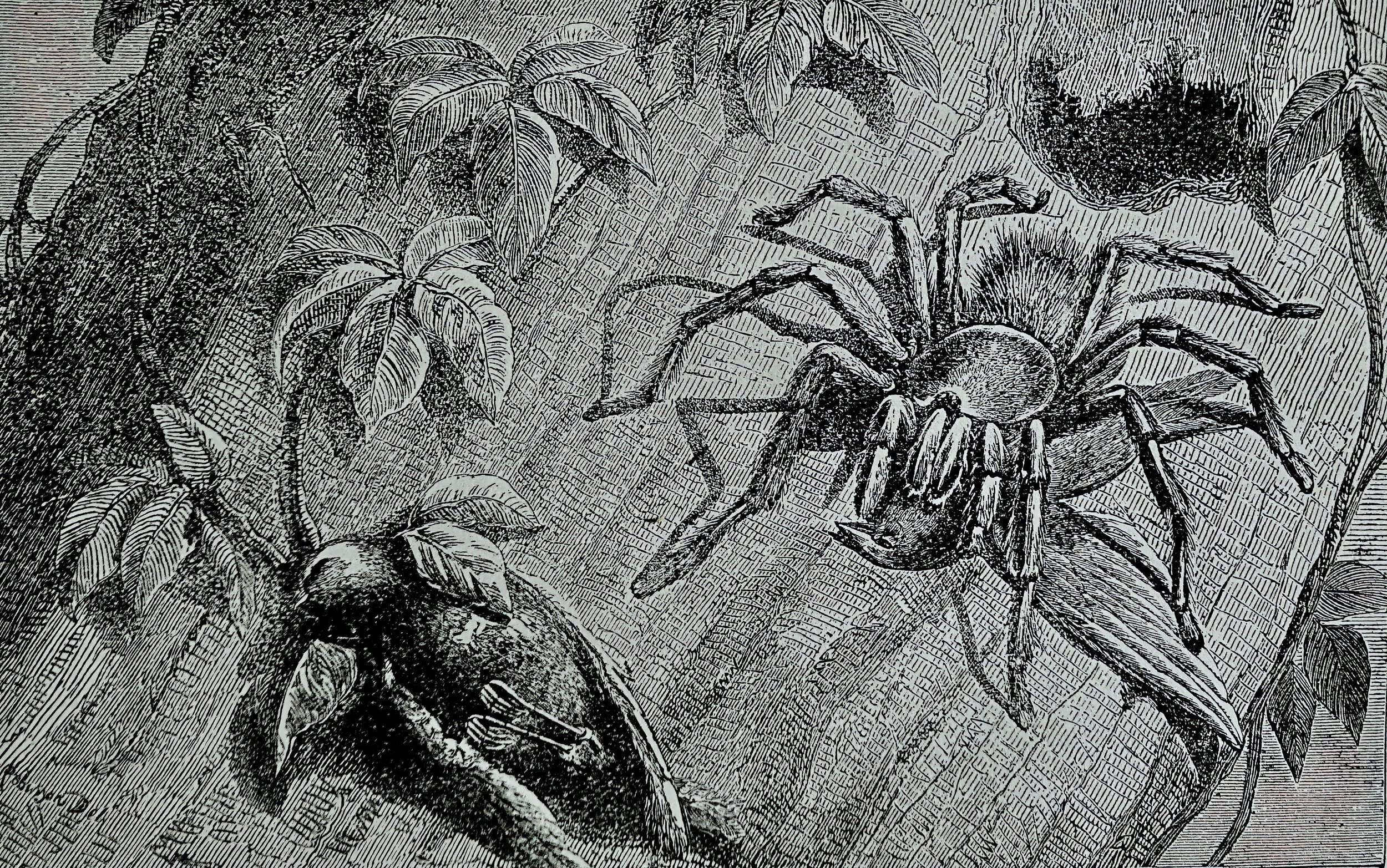

Shown above, Edward William Robinson’s classic engraving of an Avicularia avicularia feeding on birds in “The Naturalist on the River Amazons” (1863). The first-hand account by Henry Walter Bates that inspired this illustration was the first real evidence provided by a respected naturalist that many theraphosid spiders will prey on birds and other small vertebrates.

Arachnophilia? Is this really a “thing”?

You betcha! While most of the world either fears, loathes or are indifferent to them, there are a surprising number of folks around the globe that collect live exotic spiders in their homes. There are even some who not only claim to “love” their stand-offish pets but also give them names.

Yet there’s something about arachnids...

I must admit that, even after working with tarantulas, scorpions, amblypygids and sundry other strange arachnids over the years both in the field and in captivity, large spiders still give me a small case of the willies. Despite being (usually) innocuous, very interesting and complex critters, I have never been entirely comfortable sharing my close personal space with spiders if I’m not calling the shots.

An adult female Guatemalan tiger rump tarantula (Davus pentaloris). Tarantula species with red-banded abdomens of several genera are fairly common in Central and northern South America. Image: ©F. Muller.

This uneasy relationship with them does not, however, negatively bias my opinions about spiders when they’re not skating over my forearm or neck. This is a fascinating group of arthropod predators (although one remarkable Mesoamerican jumping spider species–Bagheera kiplingii–is a sometime vegan) that includes some incredibly beautiful animals. Tarantulas often show vividly contrasting or metallic colors (mostly blues and violets), females are usually long-lived (to ~20 years), and some species exhibit remarkable physical abilities and learning behaviors. Black widows (Latrodectus) dispense both excuses for unexplained, persistent skin ulcers as well as easy metaphors for crime fiction writers. Crab spiders (Thomisidae) amaze us with their floral mimicries. Brazilian wandering spiders (Phoneutria), six-eyed sand spiders (Sicarius) and Australian funnel-web spiders (Atrax and Hadronyche) provide an endless supply of internet clickbait. Despite their well-deserved reputation for cannibalism, some species are now known to be semi social or even colonial. Engineers, microbiologists and biochemists continually look to spiders, their webs and their venom for inspiration to develop new products and compounds.

Bizarre body ornamentation and bright, metallic colors are common in many Neotropical spider families, including jumping spider (Salticidae) and orb-weavers (Araneidae), making them attractive subjects for visiting photographers. In particular, female spiders of the genus Micrathena (spiny orb-weavers) that extends from southern Canada to Bolivia and Argentina exhibit some truly fantastic abdomen designs among its species that make them popular nature calendar subjects. Males differ so radically in appearance from their mates that it can be a challenge to identify them (Magalhaes et al., 2017). Colombia is the center of species diversity for the genus, with well over 50 species reported for the country.

A very colorful assortment of female spiny orb-weaver spiders is shown above. Clockwise from top left, (Micrathena decorata), Antioquia Department, Colombia. Image: ©R. Parsons. Upper right, a well-armed Micrathena sp. in Tropical Pluvial Forest, Valle del Cauca Department, Colombia, and two unidentified species photographed in Tropical Rain Forest in Guna Yala, Panamá. Images: ©F. Muller.

Amazonian pink-toe tarantula (Avicularia juruensis) feeding on a gecko (Hemidactylus sp.). Image: ©William W. Lamar.

Much of this article will focus on New World theraphosid, ctenid and lycosid spiders, commonly referred to as tarantulas, wandering and wolf spiders. All three families have species that routinely feed on small vertebrates, a fact which, I think, all of us can agree prompts a rather unsettling feeling that seeing spider-and-fly interactions does not.

Maria Sybilla Merian’s plate from Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium published in 1705, shows an Avicularia avicularia posed by a small nest with eggs, and eating a bird. This appears to be the first image of a predation event involving a New World theraphosid spider and birds as prey. Without corroborating evidence, it was widely ridiculed by scientists as being “myth” for the next 150 plus years.

That changed when Henry Bates published the image shown above of the same species of bird-eating spider (“Mygale Avicularia” = Avicularia avicularia again) feeding on a finch in “The Naturalist on the River Amazons” in 1863. Coming from such an unimpeachable source, it prompted amazement in England at the time. Since then the general public has been made aware that tarantulas will not only capture and consume small vertebrates as a matter of course, but that the New World species possess itch-inducing hairs on their bodies that they defensively shower on perceived threats.

Birds are perhaps the most disturbing type of prey that large spiders capture. Besides birds, theraphosids and other spiders - even small black widows (Latrodectes) have been observed feeding on bats, small rodents, shrews, mouse opossums (Marmosa species, pers. observation), lizards, snakes, and frogs.

A terrestrial wandering spider (Ctenus sp.) attempting to overpower a juvenile robber frog (Craugaster cf. talamancae) in western Panamanian lowland rainforest. In the recent past, Fred Muller has witnessed and documented a number of predation events by wolf and wandering spiders on several different frog families at different locations in Central America. Image: ©F. Muller.

Unidentified arboreal wandering spider (Ctenidae) in Tropical Rain Forest, Panamá. Image: ©F. Muller.

Frogs are surprisingly common prey items of many spider families. Tree and glass frogs (Hylidae and Centronelidae) are conspicuous victims of large spiders in Neotropical forests.

Fred Muller and Rory Antolak have recently observed several instances of spontaneous attacks by wandering and wolf spiders (Ctenidae and Lycosidae) on small leaf litter frogs in lowland Panamá, including the successful predation of red phase strawberry poison frogs (Oophaga pumilio). Despite possessing aposematic coloration and skin toxins the much-ballyhooed chemical defenses of these famous frogs seem to leave spiders unimpressed.

Two arboreal beauties sharing time and space in a Panamanian rainforest: a Panamá blonde tarantula spiderling, Psalmopoeus pulcher on the flowering gesneriad, Columnea pulchra. Image: ©F. Muller.

Neotropical theraphosid spiders (Theraphosidae), commonly known as tarantulas, include the largest and heaviest known spider species, the Goliath birdeater (Theraphosa blondi) from northeastern South America. While most people fear their bites, the New World tarantulas’ principal defense mechanism is to rapidly flick urticating hairs located on their legs and abdomen at antagonists and potential predators. These very irritating hairs can cause also painful eye injury and breathing problems in humans but probably prove at least temporarily incapacitating to small mammals. Bates recounts how, following careless handling of his first specimen in Brazil during its preparation, he suffered terribly for the following three days.

Shown above are two common arthropod groups sometimes confused by lay persons with dangerous spiders. Left, a tropical harvest-man or opilionid (Cosmetidae) and right, a tailless whip scorpion or amblypygid (Paraphrynus sp. - Phrynidae) in Guatemala. These harmless arachnids are often believed venomous due to their rather fearsome appearance. Both groups lack true fangs but often possess chemical defenses that are noxious to would-be predators but innocuous to humans. Images: ©F. Muller.

Large amblypygids are fearsome looking critters when viewed at close range but are retiring and quite harmless (seriously!) to all but their invertebrate prey. Image: ©F. Muller.

Most spider bites that produce noticeable envenomation but that do not involve necrotic arachnidism (an alarming, ulcerating side effect of some bites from widow, recluse, six-eyed sand and certain other spiders) are invariably described as being, “like a pin prick” or “like a bee sting”. While some of the larger species in the Neotropics have large enough fangs and potent enough venom to produce severe inflammation and significant pain, as far as I can tell, no-one has ever died from a New World tarantula envenomation.

That said, I’ve suffered some fairly painful and long-lasting bee stings in my time, so I’ll pass on voluntarily seeking “like a bee sting”-type sensations, thank you very much.

There are, however, plenty of spiders whose bites can produce symptoms just a tad more dramatic than those from a bee or wasp sting.

A large and very formidable looking adult male unidentified Phoneutria sp. perched on a cyclanth leaf (Carludovica sp.) in nature at a rainforest site in the Peruvian Amazon. This species has turned up at several lowland localities in eastern Perú. Image: ©F. Muller.

A mature male wandering spider, Phoneutria fera, shredding an adult katydid in Leoncio Prado Province, Perú. Image: ©F. Muller.

Wandering spiders or ctenids (Ctenidae) are an arachnid family that includes such fearsome critters in both urban mythology and–to a lesser degree–in real life such as Brazilian wandering or “banana” spiders (Phoneutria species). This small genus with only eight described species includes the heaviest true spider (Order Araneae), although not the one with the widest leg span (Bucaretchi et al., 2017). All species have impressive and distinctive threat displays when on the defensive that involves stretching all the aposematically banded anterior legs upward while remaining propped on the four hind legs; this pose allows the spider considerable freedom of movement, including the ability to rotate almost effortlessly from side to side.

Many larger ctenids will bite humans when they feel threatened, but especially the Phoneutria species.

Brazilian researchers have recently published conclusions that show ~4,000 envenomations involving this genus occur annually in that country (Bucaretchi et al., 2018), although less than one percent were considered “severe”. Antivenom is available and recommended for victims exhibiting severe symptoms from Phoneutria spider bites. Despite the sensational media that Brazilian wandering spiders inspire, like almost all spiders they rarely bite unless provoked. That said, some spider species take offense far more readily than others, and Brazilian wandering spiders seem to have especially short fuses. Like most large ctenids, they are endowed with blinding speed for prey capture, predator evasion and just scaring the living daylights out of hobbyists who dare test their luck with them. As is usually the case with arthropod envenomations in humans, newborns, small children and the elderly are those most at risk. The species native to urban settings in the southern Brazilian Atlantic states (but especially P. nigriventer) are those most often implicated in medically significant bites on humans (Bucaretchi et al., 2017).

Brazilian wandering spider, Phoneutria boliviensis out for a nocturnal “wander” in foohill tropical rainforest, Leoncio Prado Province, Perú. Image: ©F. Muller.

An adult male Phoneutria reidyi in foothill tropical rainforest, Leoncio Prado Province, Perú. Adult female P. reidyi and P. boliviensis have bright red basal portions of their chelicerae. Image: ©F. Muller.

The genus Phoneutria (Perty, 1833) derives from the Greek word for “murderess”. Its most infamous species is P. fera, so in free translation this spider is the “wild murderess”.

This is just the kind of designation that makes a certain type of eccentric invertebrate collector want to rush out and cuddle up with one.

Among the many unnerving side effects of Phoneutria envenomations are priapism (a long-lasting and often painful boner) and piloerection, where your hair literally stands on end…sometimes, I imagine, more from the fright of being tagged by a Brazilian wandering spider rather than a secondary effect of the venom. The intense, burning pain produced by these spiders’ bites is definitely not “like a bee sting”. Their conspicuous standup defense, aposematically-banded leg and chelicerae coloration and their venom’s dramatic effect on mammals may have evolved to deter would-be regional spider predators like coatimundis and crab-eating racoons.

Black wolf spider (Lycosidae) Guatemala. Image: ©F. Muller.

As is well-documented by regional arachnologists, medium and larger-size wandering spiders are common and significant predators of small vertebrates, particularly reptiles and amphibia, in Neotropical forest understories.

Wolf spiders (Lycosidae) share the Neotropical rainforest floor, stream-sides and human habitations with wandering spiders and, while usually smaller, are also fast and capable predators of small lizards, frogs and other spiders. A few large Old World species may also prey on very small newborn rodents and nestling birds, including the original “tarantula”, the southern European wolf spider, Lycosa tarantula (Durrell, 1969).

A rare and very colorful large arboreal sparassid spider, Olios simonsi, in northern Guatemalan tropical wet forest. While presumably fairly inoffensive, the aposematic coloration of this large spider gives one cause for thought. Image: ©F. Muller.

Huntsman spiders (Sparassidae), some of which are also known as giant crab spiders, can also prey on small vertebrates and in South Africa are known as lizard-eating spiders. Some species, mostly from the Old World, have painful and medically-significant bites but the better-known Neotropical species of sparassids are apparently inoffensive. The cave-dwelling Laotian giant huntsman spider (Heteropoda maxima) has the largest leg span of any true spider, reported at a whopping 12”/30 cm.

An adult female humped golden orb-weaver (Nephila plumipes) in nature at Jervis Bay, NSW, Australia. This Old World true spider species is among those known to capture small birds in their large webs. Image: ©R. Parsons.

Among other families of true spiders, some of the larger orb-weavers, such as Nephila maculata, N. pilipes, N. clavipes, N. clavata and N. plumipes (Araneidae) catch and kill small birds and (especially) bats with surprising frequency (Nyffeler and Knörnschild, 2013). Females of these species are medium to large fairly shy but active spiders that also are known to capture small arboreal lizards and snakes in their very strong webs. There are fairly recent images of a northern Australian species (N. edulis) killing a finch in its web that went viral on the internet. The bites of females of several species of Nephila are slightly to very painful but generally produce only mild reactions otherwise. The extremely strong silk of this genus has been used in the past to create one-off luxury garments and has also been studied extensively in order to produce synthetic spider web for industrial use.

A fishing spider (Dolomedes sp.) alongside a stream in Guatemala. Image: ©F. Muller.

Large fishing spiders (Dolomedes species and related – Pisauridae and Ancylometes species - Ctenidae), will also hunt tadpoles, small frogs and fish, in addition to such unusual prey as freshwater crabs. There is at least one verified observation of D. triton catching a wild bat in the U.S. (Nyffeler and Knörnschild, 2013). A few Neotropical fishing spiders have the remarkable ability of skating on water and spinning underwater trap webs to ensnare their prey.

Face to face with a wild Powerpuff Girl; a tiny Central American jumping spider (NOID species, Salticidae) scoping out the photographer. Jumping spiders are the largest spider family and include more than 6,000 accepted species with many more tropical species awaiting description. Despite their ubiquity, they are fascinating spiders and exhibit a wide range of behaviors and predation strategies. Did I mention that their vision is excellent? Image: ©F. Muller.

A male Lyssomanes species (Salticidae), Amazonian Perú. Males use their elongated forelegs and chelicerae in push and shove combat with other males and also to signal to prospective mates. This genus includes jumping spiders that feed on other spiders. Note the long fangs on this tiny spider. Image: ©F. Muller.

Jumping spiders (Salticidae), despite their very small size (<1”/2.5 cm), has at least one genus (Phidippus) that has recently been reported to feed on small lizards and treefrogs in both Florida and Costa Rica (Nyffeler et al., 2017). Jumping spiders include an entire group of species that are specialized spider predators themselves, and can mimic trapped preys’ movements by web tapping the outer margins to bring its occupant into striking range in order to attack them. One species diverse genus, Lyssomanes, is notable in exhibiting extreme sexual dimorphism, with males often having extremely long forelegs that are used in nuptial displays and male on male territorial combat.

A NOID Guatemalan trapdoor spider (Ctenizidae). Image: ©F. Muller.

Trapdoor spiders (Euctenizidae, Ctenizidae, etc.), are small mygalomorph spiders that occasionally feed on small terrestrial reptiles that cross their triplines. Trapdoors have proportionately large fangs that, in closeup images, look quite impressive. Although their venom is reportedly weak, some of the larger species from the Old World can be extremely defensive when even slightly provoked and the mechanical damage from the hard bite itself is apparently surprisingly painful.

Shown left, a trapdoor spider in Perú shown with the “lid” lifted. Image: ©W. W. Lamar

A mature Colombian curtain web spider (Linothele megatheloides) on the forest floor in central Panamanian rainforest. Note the greatly elongated spinnerets and silk threads trailing the abdomen. Diplurid spiders reportedly have painful bites, sometimes accompanied by unnerving side effects, but questions remain as to their venom’s toxicity to humans. Nonetheless, it seems extremely unwise to free handle them despite their apparent reluctance to bite when molested. Image: ©F. Muller.

A very beautiful female Linothele cf. fallax in nature, Amazonian Perú. This rather small species is the most attractive of the curtain web or funnel web spiders. Elongated lateral spinnerets have prompted some hobbyists to call diplurids “tailed spiders”. Image: F. Muller.

Curtain-web and funnel-web spiders (Dipluridae, Hexathelidae and Atracidae) are all formidable and potentially dangerous to deadly spiders. Diplurids seem to be the least toxic of the three families, but should by no means be assumed to be incapable of inflicting a bothersome or very painful bite. Their relative rarity in captivity and retiring nature, coupled with incomplete information about the toxicity of their venom, has lead some rather confident rare spider collectors to dismiss any risks associated with handling diplurids.

However, the bites of male examples of both the Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus) and the northern funnel-web spider (Hadronyche formidabilis) can unquestionably be full blown medical emergencies; both species are capable of killing an adult human if antivenine is not administered promptly. Because of its large fangs, venom volume and toxicity, the northern funnel-web spider is among the most dangerous of all spiders although–unlike the highly venomous Brazilian wandering spiders Phoneutria fera and P. nigriventer–fortunately have a limited range. When fully agitated, funnel-webs will rear back and exude venom droplets to hang suspended on the ends of their their upraised, prominent fangs as a warning.

Oh my! Here’s another mygalomorph that has a bite not, “like a bee sting”. The redoubtable Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus) on its home grounds just northwest of the suburbs of Sydney, at Wilberforce, NSW, Australia. Image: ©R. Parsons.

If this threat display doesn’t scare the wombats out of you, nothing will.

A brightly-colored young Avicularia rufa from the Río Momón, just north of Iquitos, Perú. Image: ©W. W. Lamar.

All of the large and showy tarantula species are now highly sought after for the pet trade, and spider collectors have become a surprisingly visible group since the advent of the internet. Like any animal keeping community its members run the full gamut from serious scientific researchers and fieldworkers to some–ahem–shall we say eccentric fringe elements. A surprisingly normal and tactful local acquaintance who shares his apartment with a few oddball tropical insect species (but no spiders) recently described arachnophiles living around the San Francisco Bay Area as, “nice, but a bit dark”.

Many species of tarantulas have wonderful metallic colors and one, the critically endangered Gooty sapphire ornamental tarantula from southern India (Poecilotheria metallica) is certainly one of the most spectacular of all terrestrial invertebrates. The arboreal trapdoor theraphosid genus Typhochlaena, endemic to central and eastern Brazil, contains some remarkably colorful species that exhibit complex behaviors and includes a few in very high demand by advanced tarantula keepers. Among these spiders, T. seladonia, discovered by Koch in 1841 but a fairly recent (and completely illegal) introduction to the hobby is also among the most beautiful of all the world’s spiders.

See a batch of unedited footage of this fascinating species in moderately disturbed natural habitat in Brazil posted by the British Tarantula Society (this link will take you offsite. Use the back button to return): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9fwG5eLpK_8

Sericopelma sp. western Honduras. Image: ©F. Muller.

Commercial traffic of the many very attractive and mild-tempered Mexican tarantula species led to their inclusion in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in two stages; in 1985 the extremely popular redknee tarantula (Brachypelma smithi and lookalikes), and in 1995 all Brachypelma species as well as a few other regional species such as Sericopelma embrithes, S. angustatum and Aphonopelma pallidum. A number of Sri Lankan tiger or ornamental tarantulas (Poecilotheria species) were listed on the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2018, effectively curtailing their interstate commerce. The legal international trade in Mexican and other Mesoamerican-origin Brachypelma species now far exceeds 5,000 captive propagated spiders annually and the illegal trade in CITES-listed theraphosids from Mexico, Guatemala and Costa Rica is also thought to still be significant (Cooper et al., 2019). Domestic trade within the U.S. and the EU, mostly of captive bred or captive hatched origin, is certainly in the tens of thousands of spiderlings and adults.

“Sometimes you’re the windshield, sometimes you’re the bug.”

The chemical arsenals of the more venomous scorps are not for bluff. They have evolved to rapidly overpower prey more than twice their body weights, and the effects on humans defensively stung by these animals can be life-threatening. Shown here, a small Peruvian Tityus sp. feeding on a large Lystrocelid katydid it has bagged in lowland Peruvian rainforest. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

It’s not only spiders who turn the tables on their erstwhile predators. Scorpions are known to be preyed on my large theraphosids in some areas, yet are they themselves extremely efficient predators of smaller spiders. Two excellent examples showing this behavior from lowland rainforest in Central America at night-time are shown above. Left, the brown bark scorpion (Centruroides gracilis) feeding on a theraphosid spiderling in Izabal Province, Guatemala; right, a highly venomous thick-tailed scorpion (Tityus cerroazul) feeding on a NOID spider in Guna Yala Comarca, Panamá. Images: ©F. Muller.

Scorpions have the advantage of immobilizing potentially dangerous prey at a distance with their pincers prior to administering a lethal sting. The species shown above on the right as well another shown left belong to a genus that includes the infamous Brazilian yellow scorpion (Tityus serrulatus). Many are considered to be among the most lethal of all terrestrial arthropods (so-called “Level 5” scorps in the hobby). These locally very common scorpions have extremely toxic venom with a potent neurotoxic component, frequently inflict severe stings, and are implicated in many human deaths across their range. This is especially notable in Brazil where the mortality rate from all envenomations by Tityus species is an alarming one percent (Abrahão Nencionia et al., 2018).

Unlike spiders and a bit under the public’s radar, scorpions are estimated to kill several thousand people annually around the world despite improved access to modern antivenom (Chippaux & Goyffon, 2008).

Taking into account both their defensive and predatory capabilities, they’re definitely formidable critters.

Peruvian Black Scorpion, Tityus cf. asthenes, is another very hot New World species with both size and an extremely potent venom that is known to be lethal to humans. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022

I know that by now you’re thinking, “Blah, blah, blah - enough already!”. What good is an article about giant, hairy spiders without some spooky giant, hairy spider stories to give you the creeps, right?

Details of fangs and underside of the cephalothorax (prosoma) of a large, live theraphosid spider in the field in Panamá. Image: ©F. Muller.

OK, well here’s a few admittedly tame tales of mine, and a very good one from tropical Africa in the 1930s.

While collecting bromeliads with a couple of fairly clueless Gringo tourists in the tropical lowlands of eastern Guatemala when I first arrived in 1975, we spotted a large colony of a particularly nice form of Aechmea nudicaulis ringing an impressively buttressed, emergent silk cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra) on the edge of a flooded pasture. Leaving the shorter man with the van, two of us headed off to scout access to the plants. When we got to the base of the tree, I found that by pulling myself up one of the steeply-sloped buttresses and then standing tip-toe on one of my companion’s shoulders, I could just reach the bases of some of the lower plants. After a bit of strenuous tugging, several of these big bromeliads tipped over, dumping several gallons on water on me and my friend but–more importantly–also dropping about a half dozen quite large, active and apparently communal arboreal tarantulas (presumably Psalmopoeus reduncus) onto my companion’s head and shoulders. In a flash he recovered from the shock of the unexpected dousing and realized that he was covered in large, furry spiders. Throwing me off his shoulders and headlong into the swamp, he went splashing off across the pasture as fast as he could run, frantically brushing his shoulders and back, and generally flinging his arms about and screaming in terror the whole way. After a minute or so of this scene, he slowly waded back to where I was and sheepishly asked whether all the spiders were off him. When I pointed out that he had one still clinging to his shirt on his lower back he ran off wildly again, repeating his earlier behavior. I had quite a chuckle about this at the time, but “history rhymes”, etc.

A large immature male Psalmopoeus victori shown in nature in foothill Tropical Wet Forest in Izabal, Guatemala. The venom of a related species from Trinidad, P. cambridgei, contains psalmotoxin and has been mentioned as candidate for the treatment of stroke victims although remains untested. These theraphosid spiders do not possess urticating hairs but some are known to be capable of inflicting extremely painful bites. Image: ©William W. Lamar.

Right after getting married in 1980, I kept a few of the showier, very placid Mexican tarantula species for a while before moving on to other interests. Sometime after I got rid of them, my father-in-law, who was a land surveyor that often worked in remote parts of Guatemala, brought me several very large, native striped knee tarantulas (Aphonopelma cf. seemanni) that he had acquired in the drier, southeastern part of the country as a “gift”. Rural boys in parts of Guatemala have a clever and unique method for capturing terrestrial tarantulas and trap door spiders for joke purposes. They roll a small ball of the dark, sticky wax made by some stingless bees around a knotted piece of string as “bait”. They then bob this into tarantula burrows (silk around the entrance often is a giveaway), trying to provoke the spider into a defensive bite on the wax ball. When the tarantula sinks its chelicerae into the wax bait, they are effectively “hooked” by their fangs, and are readily pulled free from the burrow. These relatively harmless tarantula species are then used–surprise!–to scare girls and unwary adults.

Mature female Guatemalan red rumped tarantula (Brachypelma sabulosum). This is a popular species in the exotic pet trade, often confused with the somewhat different B. vagans. Image: ©F. Muller.

At the time I was unaware that large examples of terrestrial tarantulas have very powerful chelicerae and can chew through surprisingly hard substances such as light plastic and aluminum window screen. When I was given the spiders, they were all in thick cardboard boxes, but I transferred them to ventilated deli cups and stored them on a shelf in my closet until I decided what I would do with them.

It will come as no shock to some readers who keep tarantulas that a few of them immediately chewed their way through the plastic lids in and escaped into the wilds of our apartment. The discovery of their loss prompted more than just a wee bit of alarm in our household.

I found one I short order but despite a very, very thorough search, two remained at large, much to my wife and daughter’s consternation. Late one night about a week after the escape, while in a deep sleep, my wife lightly touched my lower leg with her foot, prompting an immediate reaction on my part. Shouting “TARANTULA!!”, I lashed out with both my legs and kicked my petite, 5’ 4”/1.65 m tall, size 0 wife straight out of bed and across the room.

We never did find those two hirsute escapees and were understandably relieved when we finally moved out of that apartment. Needless to say, my long-suffering wife loves telling this story whenever she gets the chance. Despite her laughing off the accidental nocturnal assault, as well as months of worrying about tarantulas strolling around her living room in the dead of night, the incident put the kibosh on me ever bringing any large spiders home again.

Male Stichoplastoris asterix (?) Panamá. Image: ©F. Muller.

Back in the day I visited the reclusive and somewhat controversial reptile dealer Joe Beraducci at his business, the famed “Shed” in Miami, Florida. After looking around his warehouse for a bit, he and I entered his locked “hot room” to have a look-see of his inventory. In this secure area, where he housed an impressive inventory of dangerously venomous snakes from around the world, I noticed that he also had a number of adult tarantulas in large plastic containers. Among these was a gigantic and alarm-inducing chocolate brown Pamphobeteus sp. from Colombia. This adult guinea pig-sized tarantula was securely housed in a large, transparent rigid plastic canister with the threaded lid secured into place with metal screws. Certainly, it was the largest spider that I’ve ever seen either in life or image, and I’ve seen a few large captive Goliath birdeaters (Theraphosa blondi). Joe readily admitted that he was genuinely frightened of this critter and couldn’t bring himself to open the canister to feed it out of fear it might jump on him and cause him to suffer a stroke a bare minimum. Looking at this beast on the other side of a rigid plastic pane, I definitely shared his views.

It may come as surprise to many of today’s hip and oh-so-fearless tarantula keepers, but I’ve met more than one venomous snake, insect collector or natural history fieldworker who either dislikes or are unabashedly afraid of large spiders.

An adult terciopelo, barba amarilla, nauyaca or equis (Bothrops asper) depending on the region, shown in nature in lowland rainforest of Izabal Department, Guatemala. This large, common, widespread and highly venomous pit viper is responsible for more human fatalities than any other snake in the New World. Image: F. Muller.

The well-known Costa Rican herpetologist and author Alejandro Solorzano, then managing the live collections at the Universidad de Costa Rica’s venom lab (the Instituto Cloromido Picado), had a very large and forbidding-looking NOID theraphosid spider in a cage there one time I stopped by. Some time later and out of interest to see the outcome, Alejandro told me that he dropped a young terciopelo (Bothrops asper), the region’s most dangerous snake, into the spider’s tank to observe both parties’ reactions. The tarantula swiftly attacked, killed and fed on the pit viper, sin ningún problema, mae.

While conducting floral and faunal surveys of Finca Pueblo Viejo, a friend’s large estate along the foothills of the Sierra de la Minas in the lower Polochic Valley of eastern Guatemala, we had several visiting biologists engaged in fieldwork at this site as well. Among them were a pair of (then) University of Texas Arlington graduate student herpetologists, Joe Mendelson and Mark Nelson, who were there working with regional herpetofauna for almost two months in mid-1989. Living, working and field conditions in general at this site during the wet season were often very, very rough.

The tiger wandering spider or banana spider (Cupiennis salei) snacking on a roach. Image: ©F. Muller.

One rainy night while collecting mating milk frogs (Trachycephalus venulosus) in a flooded area adjacent to the Río Polochic delta, they were alarmed to find that hundreds of young banana spiders (Cupiennius sp.) were ballooning across the marsh and landing on their heads and shoulders. Some Cupiennius species are known to use ballooning as a dispersal method when young, as well as engaging in the vaguely kinky-sounding, “Drop and Swing Dispersal Behavior”, again as juveniles (Barth, 1991). These skittish and ubiquitous wandering spiders are often found during the day hiding in bromeliad tanks, as well as aroid, heliconia, banana and palm leaf axils. At night, they are commonly observed sitting out on adjacent foliage waiting for the approach of prey and can be abundant in some banana plantations throughout tropical America, hence the name.

They recounted this incident over a few drinks at a friend’s house a couple weeks later. Several of their professors from UTA were also present, including Dr. Dan Fermanowicz, a behavioral ecologist there who specializes in arachnids and who is familiar with Guatemalan spiders of medical significance. After a few more drinks, he observed that they were lucky they hadn’t been bit because the venom of some “banana spiders” (he was presumably referring to Phoneutria species) produce very long-duration erections. At that time, the upswing in rhinoceros poaching had just started, mainly because of increasing affluence in east Asia and the belief there that rhino horn is an aphrodisiac. I joked that we should probably sell live banana spiders in little plastic boxes to horny old Hong Kong millionaires with ED in order to reduce hunting pressure on rhinoceros’ populations. Someone else present, I forget who (not really), then quipped that–even better–we should think about developing an easy-to-use autoinjector kit with tiny dose of the banana spider venom and market it under the brand name PermErect™. We all had a good laugh and, I’m sure, most of us promptly forgot about the whole thing.

But we were certainly on to something.

Twenty years later, an article in Toxicon explored the potential that a toxin isolated from “banana”/wandering spider Phoneutria nigriventer venom (specifically, Tx2-6) has for the development of new drugs for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (Nunes et al., 2008). Investigation into this toxin’s role in the realization of the PermErect™ dream continues (Diniz et al., 2018 ;^)

Coincidentally, also in 1989 Pfizer stumbled on an unexpected but very interesting side effect of their experimental hypertension drug Sildenafil.

Sadly, Viagra™ didn’t save any rhinos.

Early in the last decade I was wandering around lowland Upper Amazonian rainforest near Nauta, Perú with widely-known herpetologist, wildlife photographer and author William Lamar. Flipping logs and digging through stumps on the hunt for any of several venomous coral snake (Micrurus) species that are reported for that particular region, I came across a very beefy-looking tarantula species crouched under a fallen branch. More to convince myself that was still cool with large spiders than anything else, I took a deep breath and hand-captured this formidable critter after pressing its thorax to the ground with my index finger and picking it between thumb, middle finger and forefinger. I then triumphantly (but gingerly!) went off in search of Lamar to show it off. He had recently been through this same area with well-known tarantula expert Rick West as well as arachnologists from U.S. museums, so was quite familiar with many of the local therophosid species. The sight of me holding this giant spider wiped the smile off his face and his immediate reaction was, “Uh, some of those Megaphobema species can have a nasty bite. Be careful with that thing.”

Oops.

A large female Peruvian and Ecuadorian birdeater, Megaphobema velvetosoma in nature at Yanamono, Perú. This is likely the species I found in this same area in 2001. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022

Anyone who has been on one of Bill’s field trips knows that his softly-delivered admonishment, “Please don’t do that” instantly reduces one to ant size. His rebuke delivery style should be taught at advanced corporate oversight classes.

Although I’ve been stung by Level 2 or low-tox Neotropical scorpions in the field too many times to remember, I’ve never, thank heaven, been bitten by a spider. At least that I know of. Many spider collectors on the internet boards seem pretty unfazed about getting tagged (and again with the, “It kind of felt like a bee sting”). Indeed, the allure of the whole free-handling large tarantula thing leaves me a bit baffled. As a venomous snake keeper in three countries almost continuously from age 14 to 34, I made it a point to never engage hot snakes with bare hands except when necessary. And I do mean necessary. Perhaps this is because I cut my teeth dealing in east African and Indo Australian elapid snakes, which don’t leave any margin for error, but also because it fosters carelessness and stresses out the animals to no end.

Besides the usually minor danger to the human handler, it is usually of zero benefit to the pet spider. Accidental falls by large terrestrial tarantula species onto hard surfaces invariably injure or kill them. Quite apart from that, one of these days an unlucky hobbyist is going to have a really bad “YouTube” experience with an Old World mygalomorph spider or one of the “hotter” Phoneutria species (yes, hobbyists keep Brazilian wandering spiders as “pets” in cities just like yours!) and it will result in something more than just a colorful, “oh, silly me-too” bite post on the Arachnoboards forum or elsewhere on the internet.

Spiders can change your life…

When I told my friend Peter Rockstroh (see “Meet Los Esotericos” and “Colombian Nature” sections on this website) that I was working on an article on spiders, he mentioned that he had a couple memorable anecdotes of his own.

To wit:

“My parents had always been very patient with me as an adolescent. To this day I can’t understand why I wasn’t given up for adoption, or why my parents didn’t become spokespersons for family planning. Apart from keeping all sorts of animals, large and small, I also kept the family refrigerator’s freezer stocked with worthwhile-looking road kills and sundry other animal parts. Nothing was safe. Nothing was sacred.

NOID Guatemalan solpugid/sun spider (Solifugae). Image: ©F. Muller.

Among an assortment of reptiles and amphibians, owls, parrots, a raccoon and several dogs, I also had an interesting collection of arachnids. It included a few large spiders, vinegaroons and some very scary-looking sun spiders (solpugids) All of these were kept in the animal room, a place that earned me the nickname “Eddie Munster” among my neighbors. So long as nothing escaped from the room, my parents were cool with my menagerie.

It was a Saturday morning. I had returned early (morning) from a party and at 10 A.M. I was sound asleep. I painfully woke up to my mother’s screaming, which at first, I couldn’t understand. When she came into my room, holding a shoe in her hand and pointing towards her bedroom, I got up to see what the fuss was about. She kept screaming at me, not realizing that by her first choice of words she was insulting herself a bit. When I stared at her, still totally confused as to what was going on, she changed the nature of her insult and insinuated the she and my father were not married when I was born. As she kept on pointing to her bedroom, I looked at the place she was indicating.

Then I saw the reason of her distress.

My parents had been invited to some friends’ child’s First Communion that morning. My mother was getting dressed and about to put on her shoes. She was going to put her foot in the first shoe, when she saw a large tarantula resting comfortably in it. The rest was just a violent chain reaction that ultimately detonated in my bedroom.

I took the spider back to its terrarium, mumbled an apology and went back to my room, not realizing that that was the last day I was to ever live in my parents’ house. When I returned that afternoon, I found all my clothes piled up in the front yard.

I had been evicted - permanently.

¿Do I like spiders? Well, they do bring back memories (rather ironically, of home). They don’t bother me at all when I’m prepared for their appearance, but they do give me the heebie-jeebies when they surprise me.

Over the years I’ve had many encounters with large spiders in Central and South America. Some hilarious (when they scared someone else), some terrifying (when they scared me).

Two years after “the incident” I was driving back to work after lunch. The weather was nice and pleasant, so I had the driver’s window rolled down. I stopped at a red light and, as I was looking out, I noticed a large leaf gliding from a tree. It was slowly swinging down, rocking back and forth until, right in front of my windshield, it veered left, suddenly gliding back to the right, through my car window. As the leaf was passing inches in front of my face, I saw a large unidentified spider, the size of the leaf, holding on to the edges. It landed gently on the floor of the passenger seat and the spider skedaddled away just as the red light changed to green.

As I said, I’m normally not bothered by spiders when I know where they’re coming from. But this was different. There was a very large spider, skilled enough to boogie board from a tree through an open car window, now on the loose inside my vehicle. I moved slowly forward, hoping not to feel something wiggling under the pedals and stopped at a gas station 100 meters down the road. The attendant walked towards me as I descended from the car, and without wasting time I explained the situation and asked him to help me find the elusive arachnid. His answer is a bit complicated to translate ad verbatim, but I’ll give it a shot. He replied, “¡Mi huevo, búsquela usted!” (Screw you, you look for it!). I couldn’t but laugh at his candor and responded in kind.

Reluctantly, he opened the passenger door and we started to carefully look for our eight-legged friend. After ten minutes of timid inspection I decided the spider must have jumped ship. I closed the door and walked into the convenience store to buy something to drink.

I got home and over the following days forgot all about the spider. The following weekend I was about to leave the house, when I turned around fetch my jacket, the same jacket I had been wearing all week long. I picked it up when I felt something moving in the collar. The zipper was half open and when I opened it completely a very large spider ran over the back of my hand, up my sleeve and jumped to the wall. I recognized her immediately. I had been carrying this damned spider around with me in my clothes for a week.

To this day the thought still raises the hair on my neck.”

In (almost) closing – Part I.

Celebrated fantasy author and academic J. R. R. Tolkien was reportedly bitten by a baboon spider in South Africa as a child. It seems quite likely that this experience prompted his casting giant spiders as prominent man/dwarf/hobbit/goblin-eating villains in “The Hobbit”, “Lord of the Rings”, and the “The Silmarillion”. In interviews late in his life he claimed that he remembered nothing of his bite and held no grudge against spiders.

Sure.

In (almost) closing – Part II.

The famous mid-20th century, Cambridge-educated zoologist-explorer, author and British government spy Ivan Sanderson had a deep fear of spiders despite routinely dealing with different types of tropical arachnids around the world as a museum collector throughout his life. During an early expedition to western Cameroon in the mid-1930s, while he was hard at work digging out a large ant mound in the search for burrowing snakes, he found a spider.

A big one.

His description of the encounter is one that will produce cold-sweats in any genuine arachnophobe:

“As one way (of the tunnel) led towards the ant-hill, we started cutting into the earth along its course. After a few minutes, Emére announced that it led into a chamber in which he saw something moving. I climbed down into the trench to look.

It was an extremely stupid thing to do. No sooner was my head level with the entrance than I realized this, yet in the foolhardy way that grows with experience I did not withdraw. Instead, I peered down into the gloom; before I knew what was up, something brown, woolly, about the size of my two fists held together, scuttled into the opening. I just caught sight of something gleaming like a rosette of small, cold fires, then the animal sprang straight out at me.

Image: ©F. Muller.

As it did, I felt the most terrifying coldness come over me. In a flash I let out a scream of pure terror and fell sideways into the ditch.

Luckily I moved to the left, for the giant spider just brushed by my right ear so that I felt its loathsome coldness as it shot through the air to land beyond the ditch. Had I gone to the right, it would have probably landed on my face; even if its deadly half-inch fangs had not locked in my face and set if swelling like a purple puff-ball I should have died from sheer revulsion and fright. I do not say this in jest at all; I have a loathing for all spiders that amounts to madness and renders me more or less paralytic, just as some people feel about cats, worms, birds, or other forms of life.

I was, in any case, quite paralyzed. Had Emére not hauled me out of the ditch with more than commendable swiftness, I should have been an easy prey to the horror on its return journey. I later found that the giant hairy spiders are regarded in Emére’s country as the personification of the devil, who is a far more terrifying person in their mythology than in our own. Emére felt as I did about this animal!

While I was recovering at a respectable distance from the ditch, the spider was taking six-foot leaps, first this way then that, at anybody who approached it. Though the Africans treated it with respect, they tried to catch it with their bare hands despite their knowing it to be deadly poisonous. It eventually walked back to its hole in that precise and evil way that spiders have, its bloated body slung low among its battery of angular soft-pointed legs.

We drove stakes into the ground behind the holes and gradually dug away the earth while I held a bag net over the exit. When the animal saw the game was up, it rushed out into the net. We were amazed to see that it was covered in small replicas of itself about the size of a quarter. The babies clung to their mother in a dense mass while several more dashed out after her. This perhaps was the reason for her furious attack.

When this terrible creature had been drowned, I steeled myself for an examination of her. As soon as I had satisfied myself that she was dead beyond a shadow of a doubt, I spread her out in the enamel dish that we used for dissections and other work on dead specimens. The great legs, fully extended in all directions covered the bottom of the dish exactly, from front to back and from side to side. The dish measured twelve inches by eight inches.”

(“Animal Treasure”, pp 225-227, The Viking Press, 1937)

Aside from dismissal of the “six-foot leaps” comment as excessive use of artistic license, in my opinion this seems a realistic and credible account of a run-in with a very defensive adult female baboon spider. From the description and locality, it is likely that the species Sanderson bumped into was an exceptionally large example of the Cameroon red or giant baboon spider (Hysterocrates gigas), which is known to be communal or semi-social. An even larger sibling species, H. hercules, is known from a single confirmed collection at a locality in neighboring Nigeria although there are persistent rumors that it is now available in the hobby in parts of the EU. Other baboon spiders (e.g. Monocentropus balfouri from Socotra Island, Yemen) are known to nurture their “slings” (spiderlings) for some time after hatching, so that part of the anecdote also rings very true. Many Old World theraphosid spiders (e.g. Poecilotheria species) can inflict extremely nasty bites. Large baboon spiders are known to be capable of blinding speed (what baboon spider aficionados humorously refer to as “teleporting”) and will bite with little provocation. Some have very long fangs and pack potent venoms laced with a variety of toxins. Bites by these spiders, while not fatal, can be wildly painful, have delayed reactions, and often produce extremely unpleasant side effects including persistent infections.

Since we know that “history rhymes”, almost a half century years after Sanderson wrote that passage, I had an eerily similar experience. Because I had read “Animal Treasure” on several occasions both as a child and young man, I was not only quite familiar with the incident but by that time was aware of the huge folly that is putting your face close to suspicious-looking holes in the ground in the tropics filled with reflective eyes.

Nonetheless, I did.

In closing:

“Come closer, my precious…just a wee bit closer”. Image: ©F. Muller.

One night a long time ago I was out spotlighting snakes and frogs after a heavy rain with fellow Esotérico Peter Rockstroh in climax lowland rainforest along the Río las Escobas on the Caribbean coast in eastern Guatemala. Both Peter and I share many interests, including beautiful and weird invertebrates, so we also had a few UV light traps scattered about the understory as we worked. While I was pottering around a rather steep leaf-covered embankment in the dripping forest, I came across a decent-sized burrow among the buttresses of an emergent tree. Thinking this might house something interesting, I got down on my knees and leaned into the hillside while shining my headlamp deep into the hole. Putting my face close to the entrance and peering inside, I saw a faint eye-shine and compounded my idiocy by pushing the handle of an aluminum snake stick way down as far as I could. As sudden as a heart attack, and in a hairy burst of blazing eyes a GIGANTIC black tarantula rushed up to just outside the entrance and lifted its forelegs and fangs in a very impressive defensive display. I can’t remember whether or not “I let out a scream of pure terror” like Ivan Sanderson did, but I’m guessing that I must have right before I tumbled backwards down the slope. Fortunately, the spider (Sericopelma panamensis or a Psalmopoeus victori ?), which seemed to be the size of a basketball at the time but was actually only about 6”/15 cm across, unlike Sanderson’s baboon spider was only kidding and didn’t press her home field advantage by biting the devil out of me.

Peter had quite a hearty laugh when I found him some time later with wet leaves in my hair, rueful, muddy and shaken, and told him what had just transpired.

I can still remember this event like it happened just yesterday. The image of that very pissed-off tarantula telling me right to my face to, “Get off my damn’ lawn!” still gives me shudders.

Arboreal Brachypelma species, cloud forest, central Guatemala. Image: ©F. Muller.

There’s just something about arachnids…

The bizarre but innocuous Neotropical flower crab spider (Epicadus heterogaster) in threat pose, lowland rainforest, Panamá. Image: ©F. Muller.

Acknowledgements

As always, a very special thanks to Fred Muller for doing a lot of the heavy lifting for this article by providing an amazing collection of carefully-composed images of arachnids shot in nature across Mesoamerica. Like me, Fred is extremely interested in spiders. Unlike me, Fred is very blasé about them crawling on him. Bill Lamar delved into his massive image vault and plucked out several beautiful photos of theraphosids taken in Guatemala and Perú that he generously added to the article. Thanks also to the esteemed Ron Parsons for the trio of very beautiful images shown above (esp. the Atrax) that he provided from his walkabouts around the globe.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC®, ©Fred Muller, ©William W. Lamar, and ©Ron Parsons.

Follow us on: