Beetle-juiced

by William W. Lamar

Horned Bess Beetle, Patent-Leather, or Betsy Beetle, Odontotaenius disjunctus, in Smith County, Texas. Image:© W. W. Lamar 2024.

Gleaming in the sunlight like polished obsidian, the creature resembled an ATV as it lumbered onto the pavement. It was a Passalid aptly named a Patent-leather Beetle (Odontotaenius disjunctus) crossing the sidewalk in front of my house. And it was capable of making over a dozen distinctive sounds by chafing the hindwings against the abdomen. In fact, both adults and larvae make these sounds and they react distinctly to them. The signals cover courtship, aggression, disturbance, and more; no other arthropod bears such a repertoire. But I knew none of this because I was five years old. To me it was an enormous beetle—a “Bessbug”—that made squeaking noises when I excitedly picked it up. Today, with my hearing compromised from having spent my college years chauffeuring rock stars to concerts, the sounds are barely audible. But back then it was amazing music to my young ears. It measured barely an inch and a half in length but I thought I had something worthy of the Guinness Book of World Records. It was robotic and other-worldly, yet alive. And it talked to me! So, I was obsessed…juiced, actually. Beetle-juiced.

And we all know that leads to…

Beetlemania!

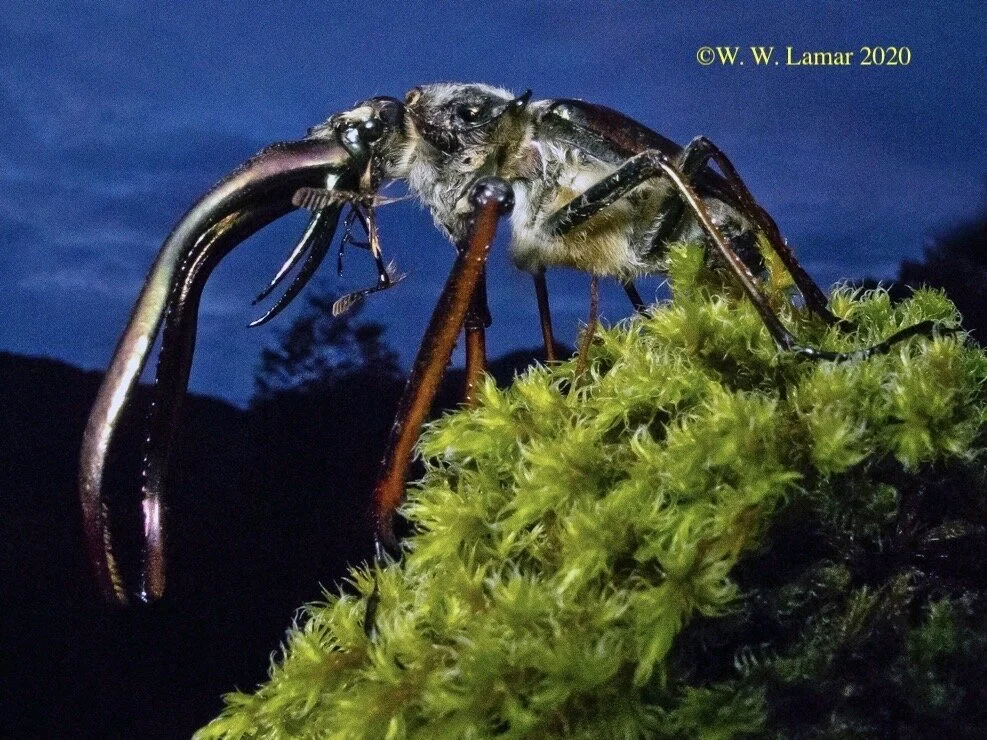

A handful of male Dynastes hercules in Peru. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Shortly thereafter I scored a real prize. During a family trip somewhere in the eastern US we spent the night in one of the myriad roadside motels that dotted the nation in the 1950s. The following morning while my parents loaded the car, I wandered the premises and there by the swimming pool, big as a hen egg and resting on the cement was an Eastern Hercules Beetle (Dynastes tityus). Doubtless the lights had lured it in the previous evening. With this stunning acquisition I had moved up the size scale past the 2-inch marker; plus the gorgeous creature in my hand was mottled like some sort of an exotic African ungulate. And it was freakishly strong. I was beside myself with wonder.

My fascination with beetles kept me entertained throughout my youth; I read and learned a lot about the species North America had to offer. Elaters, Blister Beetles, Carrion Beetles, Weevils, Dung Beetles, and more…all of them interested me. I collected moths and butterflies, so I used to paint trees with a mixture of sugar, rum, and stale beer as an attractant.

Yep, I tasted it…not bad at all.

Sure enough, it brought in a lively assortment of moths by night, but beetles came as well. I found Longhorn Beetles and other oddities that sent me digging in the library for what little literature was available in order to identify them. This was before useful works by Arnett et al. (2002), Evans (2014), and White (1983) had been published. Finding my first adult male Giant Stag Beetle (Lucanus elaphus) got me interested in jaws, pincers, and instruments of damage and destruction. That’s when I began to read about some of the world’s tropical beetle specialties. While I was in awe of Africa’s robust and colorful Scarabeids, the Goliath Beetles (Goliathus species), and Southeast Asia’s impressive Atlas Beetles (Chalcosoma atlas), it was Latin America’s offerings that really drew me in.

Naturally arguments about which is the largest insect will rage unabated. And one can parse things adinfinitum: the longest, the bulkiest, the heaviest, etc. Among the beetles it appears the title of heaviest/bulkiest for the moment goes to Megasomaactaeon (formerly M. rex.). A large male is shown on the author’s hand in Amazonian Peru and another giant specimen is illustrated below. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

The names alone provoked soaring flights of fancy: Titanic- and Metallic Longhorns, Imperious- and Giant-jawed Sawyers, Harlequin Beetles, and the Horned Scarabs…Rhinoceros Beetles and Hercules Beetles. Wow! What were they like? I had to see these for myself. And I got my chance when I took a position in Colombia working with the Smithsonian Environmental Program. My wife Nancy and I landed in Villavicencio, a bustling cow town nestled against the rugged Eastern Cordillera of the Andes. Gateway to the sprawling Llanos Orientales of eastern Colombia, Villavicencio was often referred to as “east of the Andes and west of nowhere.”

We lived in a flophouse near the central plaza while we looked for a place to rent and I walked daily to and from the biological institute where I worked. One afternoon as I approached the plaza my eyes locked on an amazing sight. Clear across the park, grasping the white stucco wall of the bank and starkly visible like a Rorschach inkblot was a male Harlequin Beetle (Acrocinus longimanus). Unmistakable owing to the exceptionally long forelegs used to prevent competing males from entering egg-laying zones, this was the iconic insect that inspired the great Amazonian naturalist Henry Walter Bates…and it really inspired me! The common name stems from the dorsal pattern, which provides camouflage in-situ on trees but otherwise looks like a stunning African tapestry. It has been suggested that the designs can be found on some shields once used by indigenous groups in South America.

Male Megasoma actaeon, Amazonian Peru. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020

Viewed out of context the wing covers of Acrocinuslongimanus seems ornate, gaudy even. Yet in-situ on corrugate or lichenose bark, these large beetles can be astonishingly difficult to discern. Image ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Harlequin Beetles have an extensive range that extends from Mexico to Argentina. They feed on sap from host trees of nine different families. Their larvae appear after eggs are deposited on dead or dying food trees and they make lengthy burrows through the soft wood, leaving distinctive holes when they emerge. The jousting matches that surround mating opportunities –with dominant males keeping others away from adult females –are carried out not only by the big beetles but also by some phoretic creatures. Tiny stowaway pseudoscorpions, arachnids of the genera Cordylochernes and Lustrochernes, inhabit the same dying trees and hitch onto emerging Harlequin Beetles, setting up housekeeping after attaching themselves beneath the wing covers via silken threads they secrete with their claws. Then they use their hosts for transport to new trees. The positioning involves males preventing competitors from joining their harems when boarding or deplaning beneath the elytra. It’s not unlike First Class and Business Elite sections on commercial airliners, come to think of it. Parasitic mites also find niches on the beetles and ride with them.

More than merely spectacular, Harlequin Beetles are traveling zoological parks.

Like many big beetles, Acrocinus are occasionally attracted to lights and I suspect the one resting on the wall of the bank had flown in the previous night and simply opted to abandon camouflage protocol and sleep it off on the stucco. But at the time I thought about nothing other than getting my hands on that beast. It was a ways up but an adjacent picture window had a sill and I reasoned that with a running start I could jump onto it and stretch up above the glass to make the catch before falling back to the ground. There were two important things that failed to figure into my calculations. The first became evident as I leapt onto the sill. Although the bank’s interior appeared darkened from where I stood, it was open for business and a heavily armored rent-a-soldier with a ponderous carbine was standing just inside that window. Airborne, I saw him as he suddenly crouched and swung his weapon in my direction. All in all, it was a reasonable response to a Gringo who was hurling himself at a bank window. Fortunately I made the grab and was immediately down on the walk admiring my catch so he lowered his gun.

And that is when I learned the hard way about the weapons Harlequin Beetles have handy and use freely.

“As distinctively beautiful as the Harlequin Beetle is, the way in which the colors and patterns blend with the surroundings is astonishing. ”

The Harlequin Longhorn Beetle (Acrocinus longimanus) has iconic status as an emblem of all that is wild and exotic in the neotropics. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

On each side of the beetle the outer edge of the pronotum bears a spike. And on either side of the beetle’s elytra there is one to match. So, when a careless Gringo grabs a Harlequin Beetle, it simply begins to rock the pronotum up and down, engaging—like crossing swords—the opposing spikes along with any meat that happens to be in the way. OUCH! Not only does it hurt like hell, but also one cannot easily rid oneself of the offending beetle. The spikes make for a firm attachment and the strong legs with clawed feet only add to the problem. Even the bank guard could see my misery; he was laughing as I made my way home with my bloody prize.

Lesson learned.

Another beautiful neotropical Longhorn Beetle with defensive spikes on the pronotum or upper thorax surface is Macropophora trochlearis, shown in Loreto, Peru. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

A Plumed Longhorn Beetle, Discopus princeps, on the Río Momon, Loreto, Peru. This spectacular beetle drew the attention of famed naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who described it in the 19th century. It reminds me of the lead marcher in a Shriners' parade. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2024.

Over the years, and especially in Amazonian Peru, I have had the pleasure of observing these unforgettable insects. Usually, but not always, it has been the occasional specimen lured in by lights in the rainforest. Once I spied a big one in a sunspot on the corrugate bark of a tree deep in the pluvial forests along the Río Tigre. I was looking for reptiles and my vision swung past the beetle but the pattern, etched in my brain so many years before, registered; so I looked back. It was a stunner! As distinctively beautiful as the Harlequin Beetle is, the way in which the colors and patterns blend with the surroundings is astonishing. Once when I was hiking near the Río Nahuapa a Cocama Indian accompanying me pointed up into the canopy. A huge Insira tree (Maclura tinctoria; Moraceae) had been lightning blasted near its crown. It oozed sap copiously and the banquet had attracted hordes of Harlequin Beetles. They looked just like the distinctive tree, whose dark bark was studded with red pustules; and there were hundreds of the beetles gorging themselves.

This was actual beetlemania! I wanted to climb up and get right into the middle of it all; right into all that beetle-juice.

Another giant and somewhat fearsome-looking cerambycid beetle from tropical America the Giant Longhorn Beetle, Enoplocerus armillatus, shows off its armor at Loreto, Peru. Exceptionally large males can exceed 6"/15 cm in length. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2024.

OK, so this is definitely not a beetle. But since I just mentioned it, why not? One of the world’s most beautiful and physically impressive arboreal snakes, the Amazon Basin Emerald Treeboa (Corallus batesii). Image ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Trees crashing to the ground in tropical rainforest are a constant occurrence and if the one falling is a huge emergent, a hoary giant soaring far above the canopy, it is a spectacular event. Dozens of smaller trees get leveled in the process. These falls are major elements of change in the forest, with regeneration bringing herbaceous growth and guild after guild of creatures that feed there. If you happen to be nearby when a big tree comes down, it is also an opportunity for finding creatures like Emerald Treeboas (Corallus batesii), Speckled Forest Pitvipers (Bothriopsis taeniata), and other treasures that live in the canopy. But you need to hurry because they don’t hang around down low for long. I once made my way to such a site; it was in a dense patch of lowland forest at the foot of the Andes north of Villavicencio. The earth shook when the crash occurred, so I rushed to the spot but it was a confusing tangle of lianas, leaves, and swaying branches. Just as I was about to abandon the place, I heard and then saw a large beetle trying to take flight; it sounded like a sputtering chainsaw. Its first attempt led to a crash against the foliage and I was there for the second lift-off, grabbing it in the air as it rose. It was a Rhinoceros Beetle (Megasoma actaeon)! Recreational drugs may have their effects, but for me none could ever equal the high of finding and holding this massive insect. The DEA will probably add beetle juice to their list of prohibited pleasures.

My first mistake was putting the prize inside my day pack. By the time I made it to the house it had wrecked everything and was deeply entangled in nylon and urethane threads. Painstakingly I picked everything off, getting repeatedly snagged and bloodied by the flailing, hooked appendages. Talk about strong! That led to my second error. Carefully I placed the writhing beetle in the bottom of a terra cotta planter and then nestled a second one in on top of it. They locked together, leaving space at the bottom for my captive. Not good enough! During the night it pushed the planters apart and crawled about the room, tangling itself in all manner of textiles. Once again I scrupulously removed all the assorted threads and returned the Rhino Beetle to its planter, only this time in addition to inserting the second pot, I added a brick to the top. Not good enough! When I got home the following day after work I found…well, you know the rest. No wonder that beetle was named for a famous Theban hero in Greek mythology.

A colorful and wide-ranging South American Dynastine scarab, Rutela miniata. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Size always seems to matter and that is certainly the case when it comes to big beetles. We’re not here to flog those wares but we can chip away at it. Unquestionably some male Rhino Beetles are among the heaviest of insects. In terms of sheer bulk, they sometimes exceed 1.25 oz/35 grams and their larvae are even heavier. While this is also not the place to debate Dynastine systematics, following the latest trend, the lumbering, massive Rhino Beetle found in the upper Amazon basin and traditionally known as Megasoma rex is now known as Megasoma actaeon. Although they appear to be black, under strong light the dorsal color of males is actually a deep maroon. These titanic beetles are denizens of lowland tropical rainforest and they are strongly attracted to bright lights at night, especially during the rainy season. Several indigenous tribes use parts of these powerful insects for adornment in the form of amulets or fetishes and in some cases, portions may be pulverized and eaten. All is done under the spurious notion that powers, sexual or otherwise, will be enhanced. The distinctive, bifurcate horn on the head aids these beetles in jousting with competitors, be it for females or for feeding sites. Much like mammals, Rhino Beetles are capable of increasing body temperature in response to cold. There are eight species in the genus and the collective range extends from the United States south to Argentina.

A large male Giant-jawed Sawyer or Sabertooth Longhorn Beetle, Macrodontia cervicornis, has a fearsome aspect but is harmless. Although it ranks as one of the three most imposing beetles in the world in terms of overall size, next to nothing is known of its life history. Río Tacsha Curaray, Loreto, Peru. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2024.

Beetle grubs, be they large or small, basically conform to a single morphotype; they're white and doubled over at midbody. Not so the larva of Macrodontia cervicornis, and this just adds to the mystery surrounding their lives. We know surprisingly little about this enigmatic beetle. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

One of the most imposing foothills where the Andes meet the llanos lies just across the Río Guatiquía from Villavicencio. It has a peculiar series of undulations up top that look like gigantic, grassy steps. One day I decided to climb up there and it proved to be more arduous than I had expected. Nearing the crest, I found the next “step” to be both steep and tall; there were no apparent footholds. At length, I spotted a small shrub growing where I could jump up, grab the trunk, and use it to scramble up a level. As soon as I grabbed hold, however, I realized I had more than the trunk; something strong was flexing within my grip but I could not let go for fear of falling. So I pulled myself up and quickly opened my hand to reveal yet another astonishing beetle. It was a Giant-jawed Sawyer, Macrodontia cervicornis. These dazzling maroon, pale brown and black longhorns are mesmerizing and fabulous.

Once again I was beetle-juiced and beside myself.

Owing to a stellar set of jaws, the story goes that these beetles can prune a sizeable branch by simply clamping on it and gyrating their way around the circumference. Allegedly a distinctive noise accompanies this action. It’s poppycock, of course. The gigantic, serrate, incurved mandibles serve some purpose and it is likely sexual/territorial because the females’ jaws are small. The fact is, we know precious little about these imposing giants. The larvae are even longer than the adults and, unlike other beetle grubs, the integument is brown and the thoracic and abdominal segments are fuzzy. In the upper Amazon basin I’ve watched Kichwa Indians expertly remove them from the trunks of dying Ungurahui Palms (Oenocarpus bataua). They are highly esteemed delicacies that are slow-roasted in plantain leaves along with the smaller cohabiting grubs known as Suri (Rhyncophorus palmarum).

Another Sawyer Beetle from South America with large males reaching just over 3"/7.5 cm in length, Macrodontia crenata is dwarfed by its huge cousin, M. cervicornis. This genus of cerambycid has much shorter antennae than most other longhorn beetles. Loreto, Peru. W. W. Lamar 2024.

By the way, the American actors Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes searched far and wide before naming their daughter Suri, which is Hebrew for “princess.” That said, it is also Quechua for oily, corpulent, and delicious grub worms.

Could be Suri the daughter will grow into that…dunno?

The name also applies to Darwin’s Rhea (Rhea pennata), a monstrously large and flightless bird, so she also has that option.

Larvae of the giant scarabs and cerambycids of the neotropics are highly esteemed and nutritious. In the upper Amazon the most frequently consumed grub is the larva of Rhyncophorus palmarum, a large weevil that commonly occurs in the decomposing trunks of Mauritia flexuosa palms but also occurs with the larvae of Macrodontia cervicornis. Called "Suri" or "Mojojoi" the grubs are cooked in Lobster Claw Flower (Heliconia spp.) leaves or on kebabs (anticucho) over hot coals. They are tasty and provide both protein and fat in a region where neither are common. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

…but I digress. Aside from the larvae and my initial capture, the only Macrodontia I’ve seen have flown in to bright lights in the rainforest. Measured from the tip of the mandibles to the tip of the elytra, the Giant-jawed Sawyer may now rank as the longest of the beetles, exceeding Titanus giganteus and Dynastes hercules.

Wait! I said we weren’t going to get into size wars.

I’d like to tell you that the circumstances surrounding my first encounter with a Hercules Beetle (Dynastes hercules) were dramatic and romantic. You know, me with oiled chest swinging somewhere on a vine while fighting off jaguars and all that. Fact is, during my years in Colombia I never found one. But one day while doing fieldwork in eastern Ecuador I was visited by a Huaorani Indian youth. He silently offered a bound Heliconia leaf dangling from a length of vine which I knew contained something alive. Focused on reptiles and amphibians I asked whether the contents might be venomous; he shook his head negatively. So, I opened it and there sat a magnificent male D. hercules!

I admit it; I got beetle-juiced yet again.

Owing to their large size, striking appearance, and scarcity the Hercules Beetle, Dynastes hercules, is a species of great interest to insect collectors worldwide. Not surprisingly, fine specimens of exceptional sizes command very high prices on international markets. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2024.

He was unresponsive to my questions so I have no idea how or where he found the big beetle. It was an overall black color but many individuals have yellowish gray elytra with scattered dark specks. Apparently, the elytra are hygroscopic and thus can change colors, darkening when the underlying layer is saturated. All giant scarabs are insanely strong but the Hercules Beetle may be at the top of the power list. Some of the lifting and pressure feats performed by these beetles are astonishing. The males use their massive medial, down-curved thoracic horn and its lower counterpart for grappling with rivals and to actually lift and carry off females. Nocturnal sap-seekers and fruit eaters, these colossal beetles occasionally show up where bright lights are shining in rainforest during wet weather. Like Bessbugs but with a much more limited repertoire, Hercules Beetle males are capable of generating sound by chafing the posterior abdominal segment against the distal edge of the elytra. They consistently emit these noises when in combat. And like the big sawyer beetles, myths exist as to their limb cutting abilities and some folks think the powder from their ground up horns has aphrodisiacal benefits. More codswallop. As an aside, the global prevalence of bogus animal-part cures for sexual inadequacies leaves one wondering whether these problems might be linked to stupidity?

“The Llico-llico was immortalized by Charles Darwin in 1871 when he wrote, “The male Chiasognathus grantii of South Chili (Chile) – a splendid beetle …”

Stag Beetles of the family Lucanidae include over 1,200 species; they are found worldwide and some, especially the Eurasian Lucanus cervus, are deeply intertwined with human culture dating back to the earliest recorded history. They have been religious and magical objects as well as esteemed pets or mascots. Ferocious symbols of power, with exaggerated mandibles analogous to antlers, stag beetles represented the triumph of good over evil in European religious iconography dating back nearly 600 years. Long before that the Greeks immortalized the beetles with this myth: The god Poseidon turned the Sperkheides (Naiad-nymphs) who frequented the Spercheus River on Mount Othrys in Malis, northern Greece, into poplar trees. He did so in order to take advantage of Diopatra, their older sister. The arrogant and precocious Kerambos (viz. Cerambos, viz. Cerambycidae), Poseidon’s grandson, was a gifted singer who devised the first panpipes and taught people how to play the lyre, on which he composed beautiful songs. He so charmed the Nymphai that they became visible to him. But he eventually began to taunt them and the Nymphai became incensed and turned him into a beetle condemned to a saproxylic life. Known to Thessalians as kerambyx, he is big, black, and hard-winged and can be seen on tree trunks where he perpetually moves his large tooth-studded jaws. The beetle’s head, which resembles a tortoiseshell lyre, is removed and worn as a pendant by boys. Perhaps owing to their sculpted mandibular architecture, Stag Beetles have always inspired artists. They are Art Nouveau objects; they appear in porcelain and on postage stamps; they adorn jewelry and a variety of consumer goods. In fact, the Stag Beetle’s presence in our culture is so ancient and pervasive that it inspired the publication of a comprehensive book (Sprecher and Taroni 2004).

One of the most distinctive and spectacular members of the family makes its home in the temperate Valdivian rainforests of Patagonian Chile and adjacent Argentina. It’s a place where green is redefined via undulant carpets of moss, Lophosoria and Parablechnum ferns, Gunnera, and Chusquea bamboos and studded with evergreen angiosperms and conifers. Prevalent Westerlies conspire with the Humboldt Current against the backdrop of precipitous Andes Mountains such that fog, mist, and rain are the norm. When things dry out a bit, beginning around Christmas, a splendid beetle that has spawned a multitude of names–Chilean Stag Beetle, Grant’s Stag Beetle, Darwin’s Stag Beetle, Ciervo Volante, Cantábria, Cacho de Cabra; and my personal choice, the Mapuche Indian name Llico-llico–emerges to fight and mate.

The Llico-llico was immortalized by Charles Darwin in 1871 when he wrote, “The male Chiasognathus grantii of South Chili (sic Chile) – a splendid beetle … has enormously-developed mandibles; he is bold and pugnacious; when threatened on any side he faces round, opening his great jaws, and at the same time stridulating loudly; but the mandibles were not strong enough to pinch my finger so as to cause actual pain.” As is often the case, the less endowed females pack a much greater punch with their mandibles although a male can draw blood if he catches you with the tips. Darwin was an avid beetle collector who wrote about them extensively and used them to illustrate evolutionary concepts.

Above left: One doesn’t normally use mammalian terms when referring to insects, but it seems appropriate to do so with this one: A bull Llico-llico (Chiasognathus grantii), surveys his realm and awaits all comers. Above right: Jousting males use their grotesquely enlarged mandibles and their unusually lengthy forelegs when closing ranks. This often takes place high in a tree in the Valdivian rainforests of Chilean Patagonia.

Below left: During their struggle, each stag beetle attempts to lock the incurved hook-like apices of their mandibles onto spurs projecting from the pronotum of the adversary. This provides the best balance for lifting. Below right: The force exerted during these epic battles sometimes results in a decapitation. A beetle will actually snap the head and pronotum off of his opponent. Otherwise, the vanquished beetle is lifted high off the substrate and tossed onto the ground. All images: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Huinay Biological Station lies on Comau fjord in the Hualaihué Municipality of the Tenth Region of Los Lagos, in Chilean Patagonia. Of difficult access, its isolation in part has provided a refuge for the Llico-llico, which is dwindling in numbers throughout its range. It is classed as rare and vulnerable, primarily owing to climate change so even the remote and pristine Huinay will not always be a haven for this imposing beetle. Iridescent in the sunshine, two males - looking for all the world like a miniature pair of Woolly Mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) - will rear up onto the middle and hind legs and engage with their extraordinarily long mandibles and forelegs. These are used to first try and grasp the lateral teeth bordering the pronotum of the opponent and then lift the combatant into the air before dropping him to the ground. As with most of the giant beetles, the males stridulate while fighting. The tussle can be protracted and considerable force is exerted such that the head and pronotum of the loser may be severed. Indeed, while working in Huinay in 2016 my companions and I encountered numerous decapitated heads scattered on the ground. If a female is present a male will stand over her and attack all comers with his mandibles. Llico-llicos feed on the sap of several species of trees and can be seen in flight, usually at dusk. They will come to lights at night. I doubt I’ll ever see Woolly Mammoths, although if cloning efforts succeed, I’ll be right there with my nose pressed to the window.

In the meantime, the privilege of having seen Llico-llicos jousting in incomparable Valdivian forest will do just fine.

Blue Tortoise Beetle, Eugenysa colossa, Lower Río Sucusari, Loreto, Peru. Image: ©D. Fenolio 2022

The Titan Beetle, Titanus giganteus, a massive cerambycid and one of the largest beetles in the world, rests on the chest of Ronald Tobias in Amazonian Peru. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Beetles! Beetles! Beetles! By a wide margin they comprise the most speciose group of organisms on our planet. Beetles occupy almost every conceivable kind of habitat; they range in size from the gargantuans discussed here to nearly microscopic. There are beneficial beetles as well as noxious pests. Beetles may be boldly colored, adorned with horns and armor, and make themselves obvious to all; or they may be cryptic, camouflaged, and secretive. They’ve insinuated themselves into our culture for millennia, symbolizing all manner of powers and virtues. As the earth and its habitats have changed through the eons, beetles have consistently exploited new opportunities.

It is alleged that the great British scientist J. B. S. Haldane, upon being queried about what might be concluded about the Creator from the study of creation, remarked that God had an inordinate fondness for beetles and stars. Aside from paying homage to the extraordinary species richness of beetles, he was making a theological point: that God’s hundreds of thousands of attempts to render his own likeness implied that his visage was more likely to be beetle or star than the rather imperfectly fashioned human.

And that leaves us beetle-juiced beetle maniacs thinking that, should we ever discover it, life on another planet might just be…a beetle!

A portrait of the above mentioned whopper, Titanus giganteus at Loreto, Peru. Image: ©W.W. Lamar 2024.

Electric Blue Weevil, Ericydeus nigropunctatus, Yanamono, Peru. Image: W. W. Lamar 2020

Macrodontia cervicornis pretty much has it all: large size, bizarre and exaggerated features, beautiful color and pattern, and they are seldom seen. Workers in remote oil camps in tropical rainforest harvest specimens lured into the bright lights and these make their way onto the international collector market. Assuming rainforest survives, perhaps our coming transition away from fossil fuels will make Macrodontia futures a hot item. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

FOR THOSE WHO ARE INTERESTED:

Beetlemania begats bibliomania and vice versa, so here are some pertinent references. If you read nothing else on the subject, you should dip into your wallet and pick up a copy of the incomparable “Latin American Insects and Entomology” by the late Charles Hogue. Not only did he manage to eloquently shoehorn fifty volumes of info into one book, but also he did so engagingly. Indeed, Hogue’s opus is the sort of thing one reads like a novel, yet it is also immensely useful as a guide. A simply phenomenal book!

ARNETT, R. H. JR., AND THOMAS, M. C. [EDS.]. 2000. American Beetles. Vol. 1: Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 443 pp.

ARNETT, R. H. JR., THOMAS, M. C., SKELLEY, P. E., AND FRANK, J. H. [EDS.]. 2002. American Beetles. Vol. 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionidea. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 861 pp.

DARWIN, C. 1871. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, volume 1. D. Appleton and Company, New York. 409 pp.

EVANS, A. V. 2014. Beetles of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princetonand Oxford. 560 pp.

HOGUE, C. L. 1993. Latin American Insects and Entomology. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 536 pp.

PAULSEN, M. J. and A. B. T. SMITH. 2010. Revision of the genus Chiasognathus Stephens of southern South America with the description of a new species (Coleoptera, Lucanidae, Lucaninae, Chiasognathini). Zookeys 43: 33-63.

SPRECHER, E., and G. TARONI. 2004. Lucanus cervus depictus. Giorgio Taroni editore, Como, Italy. 160pp.

WHITE, R. E. 1983. A Field Guide to the Beetles of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 368 pp.

Black Coconut Bunch Weevil, Homalinotus depressus, Loreto, Peru. Image: D. Fenolio

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020-2025 and ©William W. Lamar 2020-2025.

Follow us on: