The Definitive Guide to Velvet Leaf Anthuriums in Nature & Cultivation

A tour through the velvet underground

by Jay Vannini

A very attractive form of the localized Panamanian terrestrial, Anthurium papillilaminum, shown in nature. This extremely desirable species can be quite variable in leaf shape and size in cultivation and at this locality, almost certainly due to genetic influence of the sympatric A. ochranthum. ©Jay Vannini 2019.

Among ornamental tropical aroids, velutinous/velvety upper leaf surfaces are ubiquitous across both the family and within many popular genera. These include Philodendron (e.g., P. verrucosum, P. gigas, P. luxurians), Alocasia (e.g., A. micholitziana, A. reginula), Amorphophallus (e.g., A. atroviridis), Syngonium (e.g., S. rayi) and, of course, most famously in the genus Anthurium.

Primary veins on the exceptionally velutinous Colombian terrestrial rainforest aroid, Philodendron luxurians. Author’s plant and image.

Velutinous leaves and vivid contrast veins on the very popular but enigmatic Sabah native, Alocasia reginula. Author’s image.

Velvet-leaf anthuriums with contrast-colored leaf veins (esqueletos - see below) have been justifiably popular in ornamental horticulture since the late 19th century. Many currently popular species originating from Colombia and Perú, such as Anthurium warocqueanum, A. magnificum, A. crystallinum and A. regale, were first grown as denizens of European hothouses during the late 1800s. Like most delicate tropical foliage plants, they faded from cultivation following the First World War, slowly regaining popularity among western plant collectors again during the 1950s and 1960s (see Alfred Graf’s “Exotica” Series I, 1957). Some of the more attractive species are also popular as garden or houseplants in Latin America and regularly collected from nature in southeastern México, Colombia and Ecuador.

A mature Anthurium aff. magnificum “Norte” growing together with other rare plants in the author’s collection in California in 2016. Note the very prominent wings on the petioles and peduncle of this plant. Like others in this particular species complex the receptive spadices emit a strong, menthol-like scent.

All images shown here and not attributed to others are the author’s, both in nature and of his cultivated plants.

Photo of the lower leaf surfaces of two specimens of velvet-leafed Upper Amazonian Philodendron cf. lupinum. Despite efforts to mimic native conditions, cultivated plants never achieve this degree of violet saturation on their abaxials. Longest leaf shown ~12”/30 cm. Image transfer from 35 mm slide.

Epidermal cells that are micro-papillose, markedly convex or conical facilitate the capture of constantly shifting, diffuse light prevalent in forest understories. As was mentioned in the post on bullate-leaf anthurium species on this site, leaves with velvety or matte-subvelvety surfaces that are the result of the presence of these “convex lenticular cells” are assumed to shed water more efficiently than glossy leaves. While heavily quilted or bullate leaves clearly facilitate rapid leaf drying, observations suggest that this is not necessarily the case with leaves with micro-papillose dermal cells. The overall dynamics between these cells and the enivironment is probably a bit more complex than originally believed. Nonetheless, structures that facilitate rapid leaf drying would be an advantage in the permanently wet rainforest and tropical pluvial forest ecosystems these plants inhabit. Likewise, the pink or violet abaxial/underside surfaces of leaves in many of these species appear to be an adaptation shared across a wide variety of tropical forest understory plants to facilitate in capture of Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR i.e., the spectral solar radiation range of 400-700 nanometers) in deeply shaded environments. It is generally assumed that these violet abaxial surfaces have evolved to reflect significant amounts of PAR that has traveled through the upper leaf surface back into inner, chloroplast/iridoplast rich tissue where it is then absorbed.

Extreme closeup of mature Anthurium warocqueanum leaf showing micropapillose upper surface. These convex cells are what give velutinous leaf aroids their “velvety” aspect.

Anthuriums with velutinous leaf surfaces occur in wet forests throughout the genus’ range from southeastern México to southern Bolivia. There are several sections (a taxonomic category in botany just below a subgenus) with species possessing velvet or matte-subvelvety leaves. In order of importance these are:

Section Cardiolonchium includes a large selection of Anthurium, currently numbering well over 250 published or accepted species (fide Thomas Croat, Missouri Botanical Garden). Many of these are suitable for ornamental horticulture as house, conservatory or garden plants in suitable climates. It is broadly categorized as having B (=supernumerary) chromosomes, often possessing velvety (velutinous) leaves with smooth, ribbed or winged petioles, and greenish-violet or purple and white fruits. Western and southern Colombia are particularly rich in section Cardiolonchium diversity, so the final count for the section will almost certainly be higher as previously unexplored areas of the country are botanized. Note that there are a number of species in section Cardiolonchium that do not have velvety upper leaf surfaces, such as the central Panamanian endemic A. cerrocampanense as well as some populations of more widespread and variable species like A. rubrinervium/sagittatum and A. ochranthum.

Shown above right, two attractive but poorly-known section Cardiolonchium; at left the compact, terrestrial Anthurium sp. nov. “Slow Velvet”, reportedly from Perú and right, a new leaf of the hemiepiphytic A. sp. cf. triciafrankiae.

There are also a few somewhat aberrant section Cardiolonchium species in cultivation that have “odd” morphological characteristics, including Anthurium warocqueanum (B chromosomes absent, small orange fruits), together with the showy but less commonly-seen Panamanian endemics A. folsomianum and A. panamense (shown below).

Left, Anthurium folsomianum in greenhouse cultivation in California and right, A. panamense as a garden plant at the author’s home in Guatemala. This species is variable-looking in nature but exceptional forms are very attractive and can have 40”/1 m leaves. It was successfully crossed with A. warocqueanum in Australia by Chris Hall and Arden Dearden some years back, with the resultant progeny blending both parents’ leaf characters quite evenly.

Cultivated species of note include: Anthurium dressleri, A. papillilaminum, A. crystallinum, A. besseae, A. regale, A. magnificum, A. marmoratum, A. dolichostachyum (incl. “angamarcanum”), A. sp. nov. DF (is tentatively named but sp. ined.), A. forgetii, A. warocqueanum, A. waterburyanum (ined.), A. queremalense (ined.), horticulturally-designated A. metallicum, A. cirinoi, A. grande and many hybrids involving these species.

An early-issue young plant misidentified as Anthurium cf. metallicum growing potted in pure tree fern fiber in the author’s collection in Guatemala. This is a cool-growing species whose relationship with true A. metallicum Linden ex Schott is likely extremely remote.

Despite relatively few species from this section occurring there, three out of Panamá’s nine native section Cardiolonchium species are very popular with hybridizers (A. aff. crystallinum, A. dressleri and A. papillilaminum). From my perspective, the latter two species are of particular value in modern foliage-type anthurium breeding programs because they exhibit some of the most velvety-looking leaves in the genus and consistently contribute very dark color tones to their hybrid offspring. Several growers, myself included, are also working on hybrids involving the recently described A. carlablackiae and I would expect to see the first primary crosses of this species on the U.S. market in 2021.

Anthurium angelopolisense is a large, distinctly velvet-leaf terrestrial species endemic to the western slope of Colombia’s Cordillera Central. Restricted to middle and upper elevation cloud forests, it has so far evaded the attention of commercial plant poachers. There are many somewhat similar-looking green leaf section Cardiolonchium in Colombia, but with leaves to almost 40”/100 cm in length this may be one of the most impressive forms. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Section Andiphilum has a few velvet-leaf species from southeastern México and Guatemala including Anthurium clarinervium, A. leuconeurum, A. fredmulleri, and possibly a few natural hybrids believed to involve these species. Taxa now assigned to this section were formerly included in both Cardiolonchium and Belolonchium.

A very atypical terrestrial and sometimes subvelvety member of section Pachyneurium from eastern Costa Rica and extreme western Panamá, Anthurium schottianum in nature. This somewhat localized species’ proper sectional placement is currently the subject of debate. Image: F. Muller.

Section Pachyneurium has two notable species in cultivation that have subvelvety-velvety upper leaf surfaces. The best known of these is a classic birds-nest type with dark pink or violet undersides; the handsome and popular Anthurium willifordii originating from upper Amazonian Perú. Other less commonly-cultivated species that are also subvelvety include the very striking Costa Rican endemic, A. schottianum, now believed to have been misplaced in this section solely due to it exhibiting involute ptyxis.

Section Porphyrochitonium included a few of the larger species from very shady environments that also have subvelvety leaves, most notably the Ecuadoran Anthurium pallidiflorum and the southern Central American A. wendlingeri (see post on the latter species elsewhere on this site).

Interestingly, some velvet-leafed aroid species lose this trait to a greater or lesser degree over time, normally when exposed to brighter conditions. This supports the notion that strongly convex epidermal cells are an adaptation to improve capture of low light levels. However, at least one shown above, Philodendron sp. cf. lupinum, an eastern Amazonian hemiepiphyte begins life with cordate, black-green velvety leaves with violet under leaf surfaces and becomes a glossy (with plane upper epidermal cells), sagittate-leaf plant as it matures. In this case, the conversion is not the product of higher light intensity. Even plants grown in very deep shade lose their velvety appearance as leaves mature, so it is apparently leaf size - not age – that triggers the epidermal changes. Trials have shown that cutting-grown plants artificially maintained as untrellised, terrestrial runners can retain their cordate, blackish-colored, velvety juvenile leaves indefinitely.

An old cultivated specimen of true Anthurium besseae, under the expert care of Dylan Hannon at The Huntington Botanical Garden in San Merino, California. This rather small, terrestrial species is known from relatively few accessions, all in lowland Cochabamba Department, Bolivia. Most of the material in cultivation passed through Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota, Florida at one point or another. While my experience with the Dewey Fisk clone of this plant in my collection in Guatemala left me quite disappointed with its disorganized spiral growth and excessive lateral offsetting, the plant shown above is easily trained to maintain acceptable form.

Other members of sections Cardiolonchium, Andiphilum and Pachyneurium have matte-subvelvety or satiny-looking leaves throughout their lives. While less commonly-cultivated than velvet-leaf forms, a few fairly large, mostly terrestrial species have found their way into cultivation, such as Anthurium dolichostachyum, A. sp. “Purple Velvet” and A. schottianum. Some have only recently been described but are promising subjects for horticulture and are in limited cultivation (e.g., the cool-growing Guatemalan A. archilae and Peruvian A. sp. cf. triciafrankiae).

Long popular with tropical plant collectors, a number of velvet-leaf anthurium species have been hybridized over many years to produce plants with blended characteristics. More specifically, most hybridizers have sought ease of culture and full appearance required for the mass market, intensely-colored leaves and/or more distinctly-contrasted leaf veins. While many hybrids lack the visual appeal of their putative parents, there are a number of standouts that are definitely worthy of rare aroid collectors’ attention.

The very attractive terrestrial Anthurium carlablackiae in nature, growing in lowland tropical rainforest of eastern Panamá. Despite its superficial resemblance to some widespread contrast-veined Colombian species such as A. crystallinum, A. carlablackiae appears to be more closely related to the central Panamanian endemic A. dressleri and another currently undescribed species that occurs further west. This species has only recently been introduced to cultivation in the U.S. and was subsequently published in late 2020 (Croat & O. Ortiz). Image: ©F. Muller 2019.

Precocial flowering on a prized, seed-grown F1 Anthurium carlablackiae '‘Morticia Addams’. Leaf and spathe color are variable in this species, but early stage selective breeding of very dark leaf forms has resulted in improved forms over many of the wild plants. Domestically produced F2, artificially propagated and pure bred A. carlablackiae should be on the U.S. market by 2022. Author’s plant. Image ©R. Parsons 2021.

Currently, the most commonly cultivated forms include a myriad of “no-name” Anthurium crystallinum x magnificum, x A. forgetii, x magnificum hybrids and further mutt outcrosses, as well as A. clarinervium and a couple of its hybrids. Some of these, such as A. ‘Ace of Spades’, have made it to plant tissue culture (PTC) but are also often available from nurseries as second generation seed-grown plants (usually misnamed under the parent’s cv. title) or divisions. The ever popular A. warocqueanum is currently in very high demand, which has led to both increased numbers of artificially propagated and Colombian wild collected stems being offered by nurseries. A few species remain exceptionally rare in cultivation with only a small number of examples being grown outside their countries of origin (e.g. A. carlablackiae, A. sp. nov. DF and A. archilae), together with many of the newest Australian and California hybrids.

A recurring problem for people interested in these plants is the lack of the original provenance of many, even those being grown in botanical gardens. This commonly leads to confused identifications, even by very experienced botanists and amateur naturalists. Given the visual similarity of many of these plants, country of origin is a very useful piece of information to have when seeking a valid name. The plethora of NOID (no identification) south Florida, Hawaiian, Thai, Indonesian and Ecuadorean hybrids in the nursery trade can be a major challenge for botanists working to sort out cultivated material, with many hybrids now masquerading or deceptively marketed as commercially valuable species. A more recent phenomenon involves targeted marketing of NOID hybrids or Anthurium Ace of Spades and A. ‘Mehani’ (both mass market items produced clonally via plant tissue culture, propagation from stem cuttings or via offsets, and also sold from selfed seed under these names) in Asia and the U.S. as genuinely exotic crosses with one or more unlikely parents. Prospective buyers should insist on material from reliable nursery sources or where the “breeder” can clearly demonstrate his or her holding or having ready access to mature examples of both seed and pollen parents.

A still undescribed Anthurium section Cardiolonchium from Ecuador, for now referred to as A. sp. nov. DF. Due to confusion as to the true identity of Florida hybrid material identified as this species and other unpublished names, a long-overdue formal description has been written and should appear in print in late 2021 or early 2022. This plant has several key characters that readily distinguish it from other plants purporting to be it. Author’s plant and image.

Another unfortunately widespread recent development involves unscrupulous sellers who do not own the rare and coveted Anthurium species currently in highest demand deceptively “rebranding” NOID hybrid plants or other species to market them under the desired name–species or named hybrid–often for stratospheric prices. Some will also dream up exotic (and laughably unlikely) provenance to provide an air of authenticity or ethical source to their products. As of spring 2021, the internet rare plant market are chock-full of examples of these, especially in online auction site and social media plant offerings, as well as newly-minted “houseplant expert” blogs.

Incredibly, it now appears that the darker corners of the rare aroid trade have spawned the first widespread “counterfeit plant” grift in history.

Caveat emptor.

Collectors interested in any of my rare proprietary hybrids shown on this page should be aware that I have not sold any to known “plant flippers” in the U.S., nor to anyone in Asia nor the EU. A recent spate of eBay, Etsy and private offerings of mostly Indonesian-source plants that seek to dupe potential buyers has been observed and reported. Plants being offered online under my hybrid or clonal names seen here or elsewhere on the website, other than from those who can clearly trace it directly back to me (JV) in the recent past, are almost certainly bogus. The same can be said for commercial offerings of very rare or obscure velvet-leaf Anthurium species by online sellers both in and outside the U.S. that cynically seek to capitalize on current interest and are papered over with stolen or blurry photos. Casual examination of images reveals almost all are misidentified.

Discerning collectors of anything don’t collect expensive “names” just to show off; they seek exceptional quality with well-documented provenance at a reasonable market price for the asset in question. In this case, cultivating reputable sources that can point to long track records producing high quality foliage-type anthuriums are an excellent place to start, NOT Instagram nor Fakebook snake-oil vendors. To avoid disappointment going forward, beware of online plant sellers who have gained well-deserved notoriety for manufacturing rare names to order.

Leaf detail on an outstanding clone of one of the author’s new cross-sectional hybrids (Anthurium Canal Queen™ ‘Electric Kool-Aid’) created using a warm-growing section Cardiolonchium species with velvety leaves as seed parent with a section Polyneurium cool-growing, “pebbled leaf” species as pollen parent. A number of these types of crosses are showing great promise in youth and are very vigorous. Several will see limited commercial release in the spring of 2020.

Most velvet leaf anthuriums are somewhat temperature tolerant and, provided with high humidity, make excellent collectors’ plants. Many species commonly occur over 3,250’/1,000 m and a few appear to require cool nights to thrive over the long term. Some, like the giant Bolivian Anthurium grande, range as high as 7,600’/2,350 m. The majority of popular species in cultivation have leaves between 16-28”/20-70 cm in length. However, two species long in vogue, A. warocqueanum and A. regale, can have leaves that well exceed 3’/1 m in length when mature and will take up a lot of bench space when well grown. The true giants in this group, including a number in the A. marmoratum species complex, such as A. queremalense ined. and A. cf. metallicum, can have mature leaf blades from 4-6’/1.20-1.88 m long. Several climbing hybrids can also attain impressive size (e.g. Purple Mama = A. sp. “Purple Velvet” x marmoratum).

While many of these velvet leaf tropical aroids have been in cultivation since the late 19th century, surprisingly few of them have been observed in nature by other than botanists or ornamental plant collectors. They do not generally persist in disturbed habitats other than on or adjacent to recent road cuts, so visits to primary forest are often required to view them in nature.

There is a great deal of confusion surrounding the characters of one of the best-known species, Anthurium crystallinum, mostly stemming from its having been hybridized–both intentionally and not–for many decades. As early as 1951 in his book “The Cultivated Aroids”, noted aroid specialist Dr. Monroe Birdsey observed that cultivated A. crystallinum offered in the trade were “evidently” hybrids with the similar-looking A. regale and A. magnificum.

Anthurium sp. in nature, lowland rainforest Amazonian Perú. There are several of these very attractive velvety or subvelvety leaf terrestrial anthuriums from the eastern side of the Peruvian Andes. Relatively few are in cultivation, where some are mislabeled as A. rubrinervium (= A. sagittatum). Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

True Anthurium crystallinum and A. magnificum remain surprisingly rare in cultivation, although the Ecuadoran orchid nurseries have recently improved the supply of the former and also offer different ecotypes of close relatives of the latter species. Critical examination of the petioles and peduncles of domestic nursery-source plants will usually reveal hybrid origins, since A. crystallinum has smooth, mostly terete petioles and A. magnificum has distinctly winged petioles that are cuadrate or pentagonal in cross-section. Their hybrids, including F1s and complex-types, will usually show some mix of the two when their petioles are examined closely.

One close relative of Anthurium magnificum (A. rioclaroense ined.) is also known to hybridize in nature across sections to at least a pair of unknown species in at least one location in west-central Colombia. The resulting plants are quite distinctive looking but do not possess velvety leaves. I have also recently discovered intrasectional wild hybrids of A. papillilaminum and A. ochranthum growing alongside both putative parents in Panamá, and other wild hybrids involving section Cardiolonchium have also been encountered and photographed in nature by Fred Muller across northern tropical America.

Above, two extremely rare cross-sectional hybrids, one natural and the other man-made. Left, the satin-leafed Anthurium rioclaroense (ined.) x sp. section Xialophyllium (?) and right, A. subsignatum x crystallinum.

Anthurium papillilaminum putative wild hybrid, almost certainly with the sympatric A. ochranthum, growing in nature, Panamá. These presumed hybrid plants vary in appearance at this particular site, with some favoring the A. papillilaminum parent more than others. Author’s image.

Besides early crosses involving Anthurium magnificum, A. forgetii and A. crystallinum, other older Florida hybrids that are still in cultivation include A. clarinervium x berriozabalense - often misidentified as A. leuconeurum - and A. subsignatum x crystallinum (= A. x bullatum) and A. x Hoffmannii of unknown parentage but certainly involving A. papillilaminum and probably two other species. Note that this hybrid using sect. Cardiolonchium taxa is not A. “hoffmannii” shown in Graf’s “Exotica” series and is completely unrelated to A. hoffmannii Schott, a green leaf species in section Calomystrium. Another noteworthy early section Cardiolonchium hybrid made by Michael Bush at Selby Botanical Garden in the late 1970s or early 1980s that persists in limited cultivation is A. ‘Circus Peanuts’ AKA ‘Mike’s Goliath’ (A. dressleri x A. versicolor). Thomas Croat of the Missouri Botanical Garden made a cross between A. papillilaminum and A. dressleri in the late 1980s that may persist as a very rare plant in Australian collections. I owned a terribly maladapted but genuinely black leafed Australian backcross of this hybrid in Guatemala in the 2000s but remade a sturdier reverse cross in 2017 and again in 2021. Other “lost” hybrids involving A. dressleri were also made at Selby sometime after the late 1980s by then Curator of Living Collections there, Harry Luther.

Following a hiatus, there were a fair number of noteworthy hybrids made involving the three commonly-cultivated dark leaf Panamanian species from the mid 1990s through to the late 2000s, especially Anthurium luxurians x aff. crystallinum (in both Australia and U.S.), luxurians x papillilaminum, luxurians x dressleri, dressleri x crystallinum, papillilaminum x warocqueanum (and reverse), A. warocqueanum x dressleri, A magnificum x papillilaminum, A. regale x dressleri, A. radicans x dressleri and A. radicans x “crystallinum”. Only four of these hybrids show any evidence of white contrast veining, which appears to be a recessive trait unless A. magnificum is used. Most of these were made or remade by me in Guatemala; a few others were done in Queensland, Australia and south Florida. Almost all are now rarities in collections.

Exceptional modern forms include several Australian hybrids involving Anthurium marmoratum and A. warocqueanum. One of them, produced by Chris Hall and Arden Dearden at Equatorial Exotics in Queensland, Australia, A. Purple Mama (sp. “Purple Velvet” x marmoratum), is one of the finest large foliage anthurium hybrids available. It is easy to grow and propagate from stem cuttings and is extremely attractive as a pot plant. Another is my 2008 hybrid between A. regale and A. dressleri. After many years of struggling with it under cooler conditions in Guatemala and the SF Bay Area, I found that it needs much more warmth and some micronutritional tweaks to thrive. Plants moved to conditions akin to those of a classic “stovehouse” environment in the summer of 2018 suddenly spread their wings in early 2019. Now, both clones being grown here (‘Voodoo Child’™ and ‘Red Velvet’™) are showing much larger, darker and more rounded leaves. Another of my older hybrids still being grown in very limited numbers in Guatemala, A. warocqueanum x dressleri, is also proving to be a very handsome cross as it matures (see image below). Recent new hybrids of mine involving several other velvet leaf Anthurium species also look very promising as seedlings and will see limited commercial release in 2020 and early 2021.

Expanding new leaf on the original stem of my Anthurium regale x dressleri ‘Voodoo Child’™ clone, still growing rapidly at 30”/75 cm. This hybrid may be capable of leaf sizes well over 40”/1 m under optimal growing conditions. Author’s image.

Above, two very good clones of the exceptional Australian hybrid, Anthurium Purple Mama (A. sp. “Purple Velvet” x marmoratum), grown in California (left) and Guatemala (right). This very desirable plant will offset readily when mature and exceptional clones from this cross can grow 5’/1.55 m long leaves (!!!!) when given proper care and sufficient leg room.

Shown above Anthurium sp. “Purple Velvet, the seed parent of the hybrid shown above. This remains an undescribed species from northern Ecuador. Left, a large seedling in California and right Chris Hall with a beautifully-grown mature example in Queensland, Australia.

There are good Carlas and Great Carlas. Shown above left, a select, seed-grown young Anthurium carlablackiae shown expanding a new leaf in the spring of 2020 and, right, again in the spring of 2021. This clone was christened ‘Morticia Addams’ and is by no means the darkest nor finest A. carlablackiae that I grow, but may be consistently the pinkest until now. Fully expanded leaf form is much better than suggested by the images. Inflorescence shown earlier in the article. Author’s plant and images. ©J. Vannini 2021.

Mature leaf on the Ecuadoran terrestrial lowlander, Anthurium sp. nov. DF showing leaf shape and maroon colored lower leaf surfaces. Some open-pollinated Florida hybrids based off this plant are now being sold under the name A. portillae (nom. nud.) or A portilloi (nom. nud). They possess different vein patterns and are usually greenish in color when mature, not velvety blue-black.

Many velvet-leafed Cardiolonchium freely hybridize within the section. Outcrosses to attractive pebble-leaf species such as Anthurium rugulosum (section Polyneurium) are also interesting and will generate bullate offspring with very glossy, almost metallic-looking leaves. I have yet to produce a hybrid of any of the velvet leaf species crossed with a matte or glossy-leaf species and not lose the velvety aspect to the leaves to some degree, although in recent crosses using this formula a very attractive iridescent leaf aspect has surfaced in some. Contrast veining is a constant in all intercrosses between species exhibiting this character but, as was noted above, is often suppressed when pure A. dressleri and A. papillilaminum are used as parents, particularly when the offspring are young. Outcrosses to other sections such as Semaeophyllium will also yield offspring that lack contrast-colored leaf veins.

Some of the material published recently on the internet purportedly showing section Cardiolonchium crosses with Anthurium veitchii made in Thailand and Indonesia are, in my opinion, bogus. A few of them shown to me recently appear to be straightforward A. veitchii hybrids with related sect. Calomystrium or have “borrowed” images of U.S.-origin A. rugulosum hybrids from the internet to support their claims. Newcomers should be aware that many A. veitchii clones have fully peltate leaves and, when this is the case, it is a dominant trait in their primary hybrids. As is invariably the case with improbable anthurium species and hybrids “suddenly” appearing in odd corners of the global market out of the blue, evidence of their authenticity often seems lacking. Potential buyers may want to verify claims of parentage prior to spending a substantial amount of money on a plant that may ultimately disappoint.

Some modern hybrids have recently been outcrossed to produce second and even third generation complex hybrids, such as Anthurium (subsignatum x crystallinum) x papillilaminum (Vannini), A. Purple Mama (sp. ‘Purple Velvet’ x marmoratum) x warocqueanum (Hall and Dearden) and A. (faustomirandae x clarinervium) x ‘Ace of Spades’ (Rotolante). Other new intersectional hybrids involving sections Cardiolonchium, Andiphilum and others are in the works, some of which look extremely promising and will see limited commercial release in 2021 and beyond.

¿ Just what are “Esqueletos”?

An outstanding example of an esqueleto in the Huntington Botanical Garden’s research greenhouse. This is an Anthurium sp. aff. crystallinum with exceptional form and color. Grower, Dylan Hannon.

Esqueleto is Spanish for skeleton, and is a term coined to describe the contrast veined, velvety dark green anthurium leaves shown here. Obviously, it alludes to the stark white ribcage or fishbone pattern that is a large part of their appeal and is pronounced “ess-keh-let-oh”. Well known Californian plantsman Dylan Hannon, Curator of the Conservatory and Tropicals Collection at the Huntington Botanical Garden in San Merino, first introduced me to this very apt term in 2019. Dylan recalls picking it up from Colombian natural history guide, Emilio Constantino, on a trip they did together around Cali some years back. Both men deserve credit for conjuring up and popularizing a fantastic and clever name for these plants, so mis queridos esqueletos in nature and cultivation comprise a large part of this article.

And on to the menu…

Some of the most popular velvet-leaf members of the genus (all section Cardiolonchium unless otherwise noted) in cultivation include:

Anthurium clarinervium – is one of the best-known velvet-leaf anthuriums and justifiably popular with tropical plant collectors around the world. It occurs discontinuously as a very compact terrestrial or lithophyte on karst, discontinuously at low and lower middle elevations in tropical wet forest from northern Chiapan highlands along the Oaxacan border to the lowlands of northwestern Guatemalan in the Sierra de Chinajá, Alta Verapaz Department. Discovered in the early 1950s, it is now placed in section Andiphilum that all share very large bright orange ripe fruits and single seeds. Locally abundant in remote areas of its range, but threatened by over collection at known localities in Chiapas state. It requires heat and humidity to excel but can succeed as a slow-growing houseplant under suboptimal conditions if not kept too dry. It is the best member of this group for novice growers, being both small and handsome. Hybridizes freely, but fruit can take up to two years to ripen. Recent reported complex intrasectional crosses (e.g. x faustomirandae, a section Calomystrium, that was then reportedly outcrossed to a section Cardiolonchium hybrid by Bill Rotolante of Silver Krome Gardens in Homestead, Florida) look very nice, and A. clarinervium has also been hybridized with other section Andiphilum from México and Guatemala to produce more or less attractive offspring. It hybridizes in nature with A. pedatoradiatum (now considered part of same section, but formerly section Schizoplacium) and perhaps other sympatric anthuriums from the north Chiapan lowlands. With persistence (or luck) it is also reported to outcross to sections Cardiolonchium and Chamaerepium in cultivation.

An exceptionally fine example of Anthurium clarinervium shown in nature. Image: F. Muller.

This species has been widely cultivated in many countries since its description and introduction to horticulture almost seventy years ago. It is also a very popular pot plant in its native countries of México and Guatemala. Large numbers of seed grown plants are produced in southeast Asia as well as to a lesser degree in the EU, and some plants appearing on the market in the U.S. since 2018 appear to have originated from those regions. Unfortunately, a lot of this material appears to have been hybridized - intentionally or not - with a variety of species and bench hybrids, so growers interested in cultivating the pure species should compare material offered for sale with images of wild plants shown here to get some sense of what they are purchasing.

Successful long term cultivation of Anthurium clarinervium requires free draining media to allow the very succulent roots an opportunity to dry out between waterings. Sequential reduction of leaf size indicates an emergency repot is in order.

Pure species or hybrid, this is an outstanding ornamental tropical plant worthy of a place in every aroider’s collection.

A particularly nice colony of Anthurium clarinervium cascading down a rocky slope in nature in Chiapas, México. Image: ©F. Muller 2019.

Anthurium clarinervium growing wild as a lithophyte in Tropical Wet Forest in Chiapas, México. This is what most undiluted examples look like. Image: ©F. Muller 2019.

Two unusual Anthurium clarinervium hybrids. Left, (A. faustomirandae x clarinervium) x ‘Ace of Spades’ (Rotolante) in the author’s California collection and right, A. clarinervium x seleri (private grower, San Francisco)

Anthurium magnificum – a terrestrial, north central to western Colombian endemic from intermediate elevations that may include several currently undescribed species ranging south to the border with northern Ecuador. Leaves may be nearly orbicular in some populations, always showing prominent basal lobes. Petiole profiles can also vary but are conspicuously winged with quadrate or pentagonal profiles in cross-section. This species can hold large leaves, to over 30”/75 cm when well grown. It hybridizes promiscuously on both bench and in nature and in my experience its genetics usually dominate in crosses. Both the species and its primary hybrids are extremely popular with tropical plant collectors. Color and contrast tend to be improved in deep shade. Occasionally, some clones throw a few “golden” new leaves as sports in response to who-knows-what random genetic fluke before reverting to normal color.

Above left, a ”golden” leaf on Anthurium rioclaroense (an “aff. magnificum” - see below) emerging in California and, right a leaf on a fine example of a wild origin A. magnificum obtained from a Colombian rare plant grower in Guatemala that I gifted to Fred Muller in 2013. Image: F. Muller.

Left, a large wild example of Anthurium rioclaroense (ined.) growing in nature in western Colombia (Image: A. Dearden). Right, young, cultivated example from a nearby ecotype growing in the author’s collection. Note the outwardly turned basal leaf lobes on both individuals. This is a conspicuous feature in this species that is shared to a much lesser degree in some of the fully mature A. aff. magnificum “Norte” plants in cultivation.

Two outstanding leaf forms on plants currently considered to be ecotypes of Anthurium magnificum that may be described as novel taxa down the road. Left, a juvenile A. aff. magnificum “Norte” and right one of the so-called “green” leaf forms. Both plants apparently originate from north central Colombia, probably in foothill and intermediate elevation forests in the Departments of Santander and Cundinamarca. Reports of the “Norte” plant from Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador by regional nurseries are almost certainly bogus.

Three petiole profiles on new mature leaves of a trio of currently undescribed species that are closely related to Anthurium magnificum. Left to right, A. sp. aff. magnificum “Green”, A. sp. aff. magnificum “Norte” and A. rioclaroense (ined.). While all three are winged to varying degrees, “Norte” exhibits conspicuous, often frilled wings that extend to their peduncles when flowering.

Shown above, leaf details on an exceptional selection from my hybrid, Anthurium magnificum x warocqueanum (this is the ‘Big Trouble’ clone) that I made in the mid-2000s, shown above as both a juvenile in Guatemala (2007) and a near mature plant in California (2019). This cross produced very few viable seeds and is obviously dominated by the A. magnificum seed parent in terms of general aspect when young, but has the leaf venation, terete petioles and overall size of A. warocqueanum when mature. Recently, the plant shown above right has produced a leaf with a >30”/75 cm lamina.

A fully mature Anthurium warocqueanum (‘Jolly Green Giant’) cultivated jointly for several years by Cindy Hill and the author and currently housed in an intermediate to warm greenhouse in San Francisco, California. This very vigorous and handsome plant is grown in a large, vented pot with its stem mossed on a tree fern totem. The largest leaf blades shown measure 42”/1.07 m long. This may now be one of the largest specimens of this species cultivated outside of Colombia and Ecuador. Well grown A. warocqueanum should hold good leaf numbers; in this case seven and at least one more should emerge promptly. Author’s personal collection.

Anthurium warocqueanum – another large leaf western Colombian endemic, growing as a hemiepiphytic or epiphytic giant species in undercanopy from sea level elevation tropical rain forest to upper elevation cloud forest ecosystems (>7,000’/2,200 masl) in the western part of the country. The acclaimed “Queen Anthurium”, discovered by Gustav Wallis in the late 19th century in Antioquia Department and described by Thomas Moore from unnumbered Wallis collections in 1878. A well-grown plant is always a treasure to own but they do require plenty of space to show its fully mature leaves (~48”/1.25 m) off.

There are several more or less recognizable ecotypes and local variants that are worth collecting, especially the plants with long, narrow, dark green leaves and a sparse number of leaf vein. The so-called “black warocqs” or “narrow dark woqs” that reportedly originate from the lowlands of the Chocó and Valle del Cauca Departments are perhaps among the most distinctive variants now in the exotic plant trade. The very wide elevational range reported by collectors, which would now be considered unusual in this genus, raises suspicions that more than one species may be involved. Further DNA analysis by Colombian aroid specialists and molecular taxonomists may prove helpful in sorting out the relationship between populations at the elevational extremes. Please note that the defining leaf characteristics of these very desirable forms, while fixed into maturity, do not become completely apparent until the leaves are about 16-18”/40-45 cm long.

It has been successfully hybridized with several other section Cardiolonchium as well as with A. rugulosum, a section Polyneurium, in Hawaii, reputedly by either the late Karel Havlicek or David Fell. This species requires a fair amount of shade, high relative humidity and an upright support to hold a full complement of well-developed leaves (six to nine). Warmth, proximity to mist nozzles and/or a water feature nearby are a plus, although plants originating from the upper end of its elevational range (~5,900’/1,800 masl to 7,000’/2,200 masl) may require cool nights to thrive. My recent experience in California indicates that leaves will rapidly bleach or fall off seed-grown younger individuals at temperatures of 100 F/38 C or higher. Larger plants must be fogged or mossed on totems to hold high leaf numbers. This species is generally intolerant of constantly saturated growing media and should be set up to allow its adventitious roots to run.

Collectors should be aware that, once past seedling stage, this species is very prone to defoliating when maintained under suboptimal environmental conditions. Anthurium warocqueanum is not a great houseplant by any means but with patience and attention to detail it can succeed long-term in temperature-controlled interiors. Young plants will excel as subjects in large, warm, misted terraria for several years.

Anthurium warocqueanum growing as an epiphyte in nature, foothill rainforest in western Colombia. This is one of the very attractive leaf forms that is currently popular on global markets that appear to show more tolerance to heat than other ecotypes. Image: ©F. Muller 2019.

Mature Anthurium warocqueanum can achieve imposing sizes when greenhoused. This is a newly emerged leaf on the older ‘Jolly Green Giant’ shown above in the author’s California collection that, in the days following this image capture, hardened off at 15.5”/39 cm in width and 45”/115 cm in length.

Two readily differentiated forms of Anthurium warocqueanum as young F1s, shown above in 6”/15 cm pots and grown in Guatemala. Note that both plants are holding a full complement of leaves. Left, the standard green form, outcrossed true to ecotype by me and right, the very attractive “black” or "narrow dark” form selectively bred by Chris Hall and Arden Dearden in Queensland, Australia from exceptional founders and grown on from seed by me in both Guatemala and currently in California.

A young, near flowering sized wild source Anthurium warocqueanum gifted to the author as a leafless, crippled stem at the beginning of 2019; shown here in fine fettle in late April 2020. This is what some growers in the U.S. refer to as the “dark form”. This extremely handsome ecotype, reputedly (?) from low elevations in the Chocó Province of Colombia, has recently proven to be very heat tolerant under cover in south Florida and warm climates elsewhere. It certainly seems effortless to grow under my warmhouse conditions in California and has recovered completely and filled out a 6”/15 cm hanging pot in very short order.

Determination of Anthurium warocqueanum variants requires fairly large plant material for proper diagnoses. Leaf proportions in terms of length-to-width ratios, relative basal lobe height and shape, primary vein patterns and specific geographic origin, when available from a credible source, are all important things to take into account when making an identification.

Two very good clones from my 2003 remake of John Banta’s Anthurium warocqueanum hybrid, christened “Dark Moma” by him. Alternate spellings that surfaced from online exchanges that I had with U.S. aroid growers in the late 1990s and early 2000s include Dark Momma, but Dark Mama - the version popularized by NSE Tropicals - is the one that prevailed in the trade. These are nine year-old plants shown grown in a greenhouse in Guatemala in 2013. The plant shown above left is A. warocqueanum x A. papillilaminum ‘Fort Sherman’; the plant shown above right is the reverse cross, A. papillilaminum ‘Fort Sherman’ x warocqueanum. Standard green form A. warocqueanum were used in both these crosses. Exceptional clones produce leaves to well over 3’/90 cm in length and can be much darker colored than these. I sent a number of siblings of these plants to NSE Tropicals in 2006 and was fortunate to obtain a small offset back from them that I now propagate in California. I have recently remade this hybrid in California using the same A. papillilaminum parent as the one that generated these plants but with an exceptionally large and well-shaped clone of A. warocqueanum (‘Jolly Green Giant’ see above) as the pollen donor. To clarify misconceptions about naming, all simple crosses of these two parents produce A. Dark Mama, but be aware many A. papillilaminum circulating in cultivation are bench hybrids, not the true species. Crosses using these plants will not produce A. Dark Mama and will lack uniformity of appearance.

Two additional hybrids involving Anthurium warocqueanum; left, my A. warocqueanum x dressleri and right, Chris Hall and Arden Dearden’s gorgeous complex hybrid A. Purple Mama (= sp. “Purple Velvet” x marmoratum) x warocqueanum growing in my collection in California.

Anthurium papillilaminum - originally collected by Dr. Robert Dressler in the late 1960s on the Caribbean coast of Panamá in lowland rainforest adjacent to the Canal. Subsequent documented collections of wild plants appear to be rare, but this species was briefly common from seed-grown material (including some of mine) in south Florida during the early 2000s. Apparently restricted to Colón Province with a still unconfirmed record from adjacent lowland northeastern Coclé, it grows as a very localized terrestrial on very steep slopes and broken ground near sea level where it can sometimes occur close to the similar-looking A. dressleri. Surprisingly variable in leaf form and color, even within the same population, but all share slightly subterete to terete petioles and yellowish green spadices. The best forms possess almost black velvet upper surfaces and violet crystalline undersides to their long, narrow leaves. When well grown, this is one of the most attractive of all foliage aroids. Like many other velvet leaf anthuriums that were introduced to ornamental horticulture in the 1970s and 1980s, largely due to lazy cultural practices in some south Florida and Hawaiian nurseries, there are a large number of questionable plants on the market that appear to be either NOID primary hybrids or backcrosses of these to A. papillilaminum. It is now obvious that surprisingly few plants in cultivation that can trace their origins back to wild-collected material or carefully controlled crosses between origin-source plants. A recent review of images provided by U.S. correspondents confirms that most cultivated plants appear to have been diluted with other related species. A spring 2021 internet search by the author showed almost no authentic A. papillilaminum being offered for sale or being shown-off by online vendors. Cautious buyers should look for plants with clear, credible parentage from the only reputable source now known to grow it in pure form and not just a “label” on something that “could” (?) be an A. papillilaminum.

Anthurium papillilaminum has proven to be one of the most valuable species in the genus for breeders seeking new plant forms. Above, a young example of my primary hybrid A. Curandero (A. sp. nov. x A. papillilaminum ‘Fort Sherman’), eight months into a trial in my living room as a houseplant. This robust hybrid is very tolerant of exposed conditions in modern interiors and can produce extremely saturated leaf colors even under fairly bright and dry conditions. The image on the right is a time exposure of the plant illuminated with longwave ultraviolet light at 365 nm. All “black velvet” anthuriums exhibit vivid red longwave UV reflectance somewhat equally, but some are definitely more equal than others!

For more information on UV fluorescence in tropical ornamentals, please see the article on the website linked here: https://www.exoticaesoterica.com/magazine/plantuvfluorescence

The three better known localities where Anthurium papillilaminum have been observed and collected in nature can be generally defined as isolated locations along the western bank of the Panamá Canal, to the north of Lago Gatún, and in the vicinity of Portobelo; all in Caribbean coastal rainforest relics and reserves in Colón Province. There is a recent record of a group of plants reportedly photographed in northeastern Coclé Province, also in the Caribbean lowlands.

For reference purposes, young flowering-sized plants of known, wild-collected origin are shown below together with some of their first generation artificially propagated offspring.

Author’s plants and images. Photographed with natural light under bright greenhouse conditions (~950 fc/10,225 lux), so colors depicted are true to life.

Gallery

Above, new leaves on two very handsome wild origin Lago Gatún type Anthurium papillilaminum. Left, ‘Green Genie’ and right, newly emergent leaf on ‘#5’/‘RA#5’. Both these plants originated from precisely the same location. As the leaves on both clones mature they darken substantially.

Young offset-grown examples of two exceptional wild origin Panamá Canal-adjacent origin Anthurium papillilaminum I have been working with for decades. Left, ‘Ralph Lynam’ and right, ‘Fort Sherman’. In breeding, these plants show no evidence of natural hybridization with Anthurium ochranthum and produce offspring with uniformly dark upper leaf surfaces with pink to reddish violet lowers. Selfings and hybrids that involve these clones are also fairly uniform, but some very desirable variants pop up as rare outliers in every large seedling batch (see below).

Above, a pair of F1 Anthurium papillilaminum seedlings of the two locality types shown above, recently transplanted to 3.75”/9 cm plastic baskets. Left, a young example bred from two wild-collected Lago Gatún founders and right, a ‘Ralph Lynam’ x ‘Fort Sherman’. Both plants are currently being grown under fairly bright conditions on open greenhouse benches, so are expected to become much darker under optimum light conditions.

I do not cross plant material from these two ecotypes and suggest responsible growers interested in keeping their breeding lines distinct follow suit unless using them to create clearly identifiable hybrids. At this point (Fall 2021), plants from a population recently reported much further west from the type locality in Coclé Province (that have dark green leaves) as well as those on the eastern boundary of its known distribution near Portobelo (that are dark) are not to my knowledge in cultivation outside of its country of origin. The very real possibility exists that–as is the case for a recently discovered sibling species from eastern Panamá–at least one of these populations may prove to be an undescribed taxon.

Above, two nice variations of the Anthurium papillilaminum ‘Fort Sherman’ x ‘Ralph Lynam’ cross. The intense violet lower leaf surfaces of many shade grown examples of this species are especially evident in a new emergent leaf in the background of the image on the left. This particular examples was selected at random from a group of small seedlings for a home cultivation trial and spent six months as a “houseplant” in a 2.25”/6 cm pot in my kitchen bay window before it started showing inky dark leaf color despite exposure to afternoon sunshine. Many of my clients have ended up with very similar looking plants from this cross. The plant on the right, shown in a 3.5”/8.5 cm pot, is a fairly typical looking seedling from this cross when grown bright.

Above, two large seedlings of of the “dagger” or lance head-shaped leaf variants of Anthurium papillilaminum ‘Ralph Lynam’ x self in 3.75”/9 cm baskets. Spreading basal lobes are characteristic of this selfing, but the combination with very elongated and narrow leaf blades like the plant shown left occurs in only about one in 50 plants.

A tiny number of plants in cultivation in the U.S. now appear to be green or dark leaf first and second generation hybrids derived from A. sp. nov. DF from Ecuador that was distributed for a brief period in the early 2000s in small numbers by Dewey Fisk as “Ecuadorean papillilaminum” via offsets taken off two wild-collected plants. Recent research by the author now indicates that only one clone (shown in two images further up the article and one shown lower right) is known to have survived unadalterated in the U.S., and that the vast majority of plants being marketed currently are a hybrid swarm with unknown pollen parent/s, or selfings of these odd hybrids. Two unpublished binomials currently applied to these plants are A. “portilloi”, a unpublished synonym of A. sizemoreae Croat (Croat, pers. comm.), which is an unrelated, dissimilar looking, high elevation central Peruvian epiphyte or climber, and A. “portillae” (nom. nud.), an orphan place marker name that, because I formerly used it in error, has caused me a lot of headache of late.

So, to make it clear to those aroid collectors and nursery owners who apparently still don’t get it: A. “portillae” = A. “portilloi” = A. sizemoreae Croat (a valid sp. ined.). Anthurium sizemoreae preserved type material looks completely different to both A. sp. nov. DF and the blizzard of hybrid plants that apparently derive from it sold under a variety of names.

New leaf expanding on a young Anthurium sp. nov. DF in the author’s California collection. This species has very vivid new leaf color, especially when small. Author’s image.

Along these same lines, an avalanche of unremarkable hybrid plants are now being offered for sale on the internet purporting to be “genuine”, “guaranteed”, or “cross-my-heart-and hope-to die!!!” Anthurium papillilaminum. A cursory examination of the leaf vein patterns and general aspect will quickly reveal almost all of them to be misnamed. Once again, there are very few pure A. papillilaminum founders surviving in cultivation nowadays, although renewed interest in it has prompted other U.S. collectors and me to produce crops of first generation seed-grown plants from select clones of known wild provenance to satisfy market demand for plants with “pedigrees". Infusions of wild genetics from selected plants from a new locality–if managed responsibly–will prove a boon to foliage anthurium breeders in the very near future. Unfortunately, one promising early U.S.-based initiative that began with a stable of very nice looking wild-origin stud plants in late 2018 and that produced some excellent F1 seedlings until early 2020 has now diluted this once valuable genetic resource with domestic “papillilaminum” and God-knows-what-else and veered off the rails.

Ironically, I have recently read that a few vendors of NOID hybrids around the the world have asserted that due to the uniformly very dark leaf colors seen on selections of provenanced F1 Anthurium papillilaminum seedlings that another U.S. breeder and myself have brought to market since late 2019, they “must” be A. x Hoffmannii since they bear little or no resemblance to their own offerings.

You can’t make this stuff up…

Two very nice forms of Anthurium papillilaminum. Left, new green leaf on a wild plant photographed in nature at the type locality with slightly overlapping basal lobes and right, newly emergent leaf on a first generation seedling of a 1980s-vintage collection of mine (‘Fort Sherman’) crossed with another Panamá Canal proximate plant (‘Ralph Lynam’). Note that plants with spreading basal lobes occur together in nature with plants that have overlapping basal lobes. Low basal vein numbers are characteristic of the species and are one of several useful key characters. This elongated “black velvet” and quilted type is one of the most desirable leaf form in cultivation and leaves in well-grown mature plants can reach 24”/60 cm in length. Both plants show pink to pale violet colors on the undersides of their leaves. Despite setbacks involving putative wild hybrids, recent additions of Lago Gatún vicinity genetics to U.S. anthurium foliage-type breeding programs should expand the availability of both A. papillilaminum and their better primary hybrids as we move forward.

A noteworthy undescribed Anthurium species sometimes confused with A. crystallinum and also incorrectly marketed as “A. besseae aff.” by Ecuadorean nurseries. The latter species is a central Bolivian endemic from lowland tropical forest, as shown above. The plant in this image has been reported from lower montane rainforest on Cerro Pirre in the Darién Province of Panamá and on into northwestern Colombia. It has a pinkish spathe, a bright green spadix and a very pleasant, distinctive fragrance of pineapple when in flower. Author’s collection.

Anthurium crystallinum – is a terrestrial, lithophytic or epiphytic species with bold contrast veins, lightly marked terete petioles and tan to yellow spadices. Some Panamanian plants from premontane forests in the Darién Province such as Cerro Pirre that are currently lumped under this species may exhibit slightly subterete petioles, darker leaf color and fewer leaf veins arranged quite differently than the plant shown below. Basal lobes on these western populations also do not appear to meet or overlap like those in Colombian plants. Likewise, spadix scent at anthesis, while pleasant, also differs markedly from true A. crystallinum. Other than these populations, for two decades I have grown a wild-collected accession from a collection near the Darién in Panamá that was tentatively (mis) identified as A. crystallinum by a specialist in the late 1990s. Among other things, it lacks the contrasting leaf veins that identify this species and is much closer to the description Cerro Pirre-type plants and A. papillilaminum than to A. crystallinum although it has a somewhat different ripe fruit color than both of these species. This undescribed taxon is in very limited cultivation, may have recently been rediscovered in nature and has great ornamental potential due to its exceptional tolerance to warm temperatures. Anthurium ‘Crystal Hope’ appears to be a small sport or, far more likely, a hybrid with vividly-marked leaves that was propagated on in PTC by the Ball Seed Co in 1994. While it certainly has showy individual leaves, it is finicky and maladapted in cultivation and difficult to maintain as an unclustered plant. The so-called ‘Selby Clone’ looks like the same plant under a different label, as are some Asian "cultivars” sold under a variety of different clonal names. Several individuals I know in the U.S. have expressed keen disappointment after spending a considerable amount of money collecting all these different “names” only to find a year or so later that they have a trio or quartet of identical-looking, clonally-propagated plants once the material has fully acclimated to their growing conditions.

Immature leaf of wild-origin Colombian Anthurium crystallinum in cultivation in California. This young individual matches 19th century images and descriptions almost perfectly.

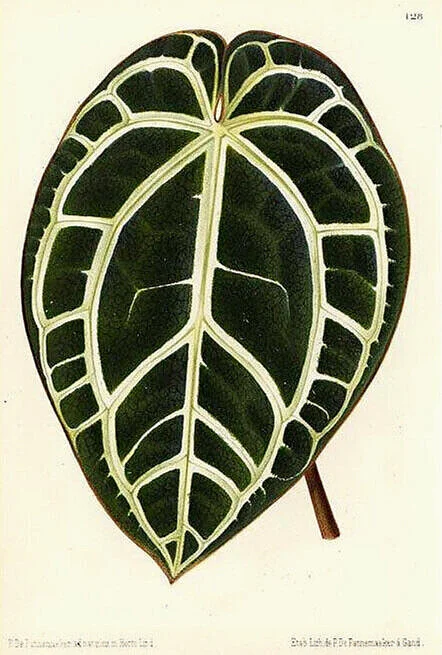

One of Jean Linden’s plates showing true Anthurium crystallinum in L’Illustration Horticole. Drawn by Pieter de Pannemaeker from life in 1873. Compare with plant shown above.

This plant remains surprisingly difficult to obtain as a pure species. Some seed-grown and propagates of wild-collected Colombian-origin plants are beginning to make their way back into horticulture in larger numbers from Andean country nurseries, which is a welcome development for collectors. Plants sold in the U.S. exotic plant trade with reddish or maroon new growth, as well as exceptionally large-leaf forms and labelled as this species may (rarely) either be part of an array of undescribed, but related species or (far more frequently) betray their hybrid origin. Older hybrids that are routinely sold as A. crystallinum include: x forgetii, x magnificum, x regale and x dressleri, as well as mongrel backcrosses to these primary hybrids. Both A. crystallinum and A. forgetii often have vivid red emergent new growth. Recently, some teratogen-treated hybrids have appeared on the Asian markets with nearly orbicular leaves. While quaint, they bear no resemblance to any wild forms.

Anthurium Foxy Lady (A. crystallinum Hort. x warocqueanum), an old Australian hybrid grown to perfection by Chris Hall and Arden Dearden in their Queensland collection. I have recently remade this cross with Antioquian origin A. crystallinum and an exceptional A. warocqueanum pollen donor. Image: ©Arden Dearden 2021.

A mature leaf on an interesting, undescribed terrestrial Anthurium sp. reportedly collected in the 1990s by a botanist in the Darién Province of Panamá and previously misidentified as an A. crystallinum at a U.S. botanical garden. Its leaves, slightly subterete to D-shaped petioles and elongated inflorescence place it fairly near to A. papillilaminum, although it differs from that species in several key characters. This beautiful plant is also visually similar to another recently discovered, very dark leaf species from eastern Panamá that is also unpublished. Images of wild plants now circulating online as well as this image show these two undescribed taxa to be among the most attractive forms in this group. Author’s collection in California.

Anthurium willifordii - this velvet-leaf birds-nest type appears to have been collected on very few occasions in Loreto Department, Perú. It was briefly put into PTC in the late 1990s. I found it in nature in 2000 as an apparently rare understory epiphyte growing adpressed to tree trunks about 25 miles/40 km airline southwest of Iquitos from where Charles MacDaniel, Jack Williford and others collected it in the 1980s near the Explorama Lodge. I hybridized this species with A. reflexinervium as the seed parent several years later. The resulting hybrids (A. Río Napo Ripples) have very attractive satiny, undulate-textured leaves, although lack the pollen parent’s violet colors unless grown very shady. While easy to grow, they are fairly cold sensitive, as is A. willifordii.

I have recently produced several batches of seedlings of a sibling cross of this hybrid and several unique-looking offspring have emerged from this experiment.

Together with other birds-nest anthuriums such as Anthurium superbum, A. hookeri and A. jenmanii, this species was in such high demand in Indonesia from 2007 to 2008 that larger plants routinely sold for staggeringly high prices, even by current standards.

Both Anthurium willifordii and A. reflexinervium are considered to be rare and threatened species in nature with limited known distributions. The latter species in particular has been subject to heavy poaching pressure by commercial interests for more than two decades and is now either very rare or nearly extirpated near the type locality in the Huallaga Valley, Perú (F. Muller, pers. comm.).

Above left, wild origin Anthurum willifordii growing in a commercial greenhouse in Guatemala. Right, my old primary hybrid A. Río Napo Ripples™ (A. reflexinervium x willifordii) growing in California. Both are great plants that require warmth and high humidity to look their best.

Anthurium dressleri, near type locality form in nature. This species is often found with its leaves partially or completely skeletonized by caterpillars or leaf cutting ants (Atta species) at some sites. Image: F. Muller.

Some of the rarer forms in cultivation include:

Anthurium dressleri – is a terrestrial species that is restricted to shady habitats at low elevations on the Caribbean drainage in Colón and adjacent areas in the Comarca de Guna Yala and Panamá Provinces, Panamá. Leaves may be similar to those of some A. papillilaminum forms but it is easily distinguished by its distinctly winged versus subterete petioles, short versus long peduncle, white or whitish spathe and bright yellow spadix versus a combination of green and violet spathe and green spadix colors in A. papillilaminum. Some specimens reported from near the Continental Divide in Panamá and the Comarca de Guna Yala (= San Blas) represent another species, A. kunayalense, or natural hybrids between the two. Recent observations of plants from a number of different localities across its range show notable and consistent variation in leaf form and texture as well as spathe + spadix color and almost certainly represent different species. It was widely used in hybridizing following its discovery in the 1970s, where A. dressleri usually contributes its very dark-colored and distinctive velvety leaves. This is particularly evident when out-crossed to equally dark or darker-colored species, which may then produce violet-black new leaf colors in shade-grown plants (see A. ‘Voodoo Child’ here).

Young, artificially propagated F1 Anthurium dressleri of the Río Guanche ecotype, very dark leaf form. Author’s California collection.

Slow-growing and oftentimes fussy in captivity, but well worth every effort to keep it happy. It is fairly water quality sensitive and, especially in the case of plants grown in sphagnum, will tend to crash if irrigation water is hard. Extremely difficult to grow from seed and high mortality for seedlings is the norm. Under perfect growing conditions - i.e. uniformly warm, humid, very shady, RO water irrigated, properly fed and grown in a well-drained, acid substrate - some exceptional examples of this species produce some of the “blackest” leaves of any Neotropical aroid. Happily, its hybrids are usually fairly easy in cultivation. Line breeding by me has brought out darker leaf colors in F1s and F2s; my friend Peter Rockstroh grew out several dozen plants from a seedling batch of mine in Guatemala and ended up with several extremely dark clones that he grew successfully as houseplants. Recently, I have also found a few “black” leafed individuals among an F2 seedling batch of mine in California. Surprisingly cold tolerant for lengthy periods, but very prone to aroid blight (Xanthomonas campestris pv. dieffenbachiae) as well as less aggressive bacterial infections when grown under sub-optimal conditions. The leaves on cultivated plants should not come in physical contact with any other plants to check leaf friction trauma and associated development of marginal lesions. Young plants are especially prone to yellowed lesions and malformations caused by even brief contact with hard surfaces.

Despite the challenges it often poses in cultivation, as of late spring 2021 Anthurium dressleri was among the tropical aroid species most in demand by specialty collectors around the world. Unfortunately, this new wave of demand willing to pay very high prices has driven an unhealthy interest in this and other rare and showy Panamanian aroid species by “poach-to-order” suppliers located in the U.S., Asia and northern Latin America. Based on very recent past experience with other regional Anthurium and Philodendron species coveted by rare plant collectors, it is a certainty that significant numbers of freshly collected stems of this species stolen from nature in Panamá will find their way to world markets sometime in the second semester of 2021 and beyond. Environmentally-conscious buyers interested in acquiring this species should be aware of this likelihood going forward and make their purchase decisions accordingly when offered cutting-grown plants that have “magically” materialized for sale online. There is a growing volume of artificially propagated supply of this species in cultivation in several countries–now into third generation in my case–and no rational justification why this species should be subject to additional wild collecting pressure by commercial interests.

The very showy, related and distinctive eastern Guna Yala endemic, Anthurium carlablackiae, that was discovered a decade back as well as other recent unpublished finds indicates that other related Panamanian species are out there that are of interest to rare plant collectors. So far, A. carlablackiae appears to to be more like A. papillilaminum rather than A. dressleri in terms of degree of difficulty in tropical culture. Several collectors who obtained plants early on have found it surprisingly easy and fast growing in cultivation although it is intolerant of prolonged spells of high temperatures and high light levels. Wild-origin plants, even those grown from stem cuts, are reportedly prone to crash without warning. First generation seedlings of this species, grown from select founders are gradually becoming available in the U.S. and should fully substitute vegetative propagations from wild-collected plants by 2022.

Above left, wild-origin founder Anthurium dressleri ‘#3’ in Guatemala; right a mature F2, line-bred A. dressleri growing in California. Leaves in fully mature examples of good selections can be about a third larger than those shown above.

Right, a uniquely-colored clone from a hybrid of mine (‘Blue Boy’) between Anthurium dressleri ‘#2’ and an A. debile ex-Huntington BG that has leaves with strong steely-blue overtones inherited from the pollen parent. Only two seedlings survived from this cross and they seem extremely fragile after just over two years in cultivation. It remains to be seen whether the bluish leaf color is maintained into maturity. Background leaves are of Philodendron lynnhannoniae.

An overgrown compot with several four year-old, F1 green phase Río Guanche origin Anthurium dressleri at the author’s home in Guatemala. Leaf color and–to a lesser degree–shape can vary in this species, even within plants originating from the same locality. Author’s image.

Friend and fellow Esotérico Peter Rockstroh (see “Colombian Nature” elsewhere on the website) grew a large seedling batch of my F1 Anthurium dressleri from the Río Guanche, Colón Province ecotype from 2003 until 2013. To say that Peter is a talented horticulturist is a major understatement. He grows everything that interests him - ferns, orchids, aroids, nepenthes and especially tropical aquatic plants - to the highest standards possible. After discarding a large number of what he considered to be mediocre young plants, he selected several clones for vigor and exceptional color. Greenhouse grown for most of their lives, he cultivated two as houseplants in his Guatemalan home (shown above left in 2013 on a dining room sideboard and right on top of his refrigerator) as well as another very nice example in his office. Peter’s local conditions, exceptional attention to detail and incredible knowledge base allowed him to grow these rather finicky plants to leaf perfection on a consistent basis. This is something no-one else that I know, including me, has achieved over the long term. These images clearly illustrate what a spectacular plant A. dressleri is when well-cultivated and why it is so popular with rare tropical aroid collectors. Fortunately, the captive genetics shown here survive in Guatemala and California. Unfortunately, most A. dressleri do not have this spectacular near black velvet leaf color, which seems a recessive trait. Again to the upside, it has resurfaced in a very small percentage of my line bred F2 seedlings produced in both Guatemala and California and also persists in natural populations.

*August 2022 edit: Starting in late May of this year, the author began a limited commercial released of line-bred, third-generation Anthurium dressleri seedlings based on the original Río Guanche accessions made more than two decades ago. These plants should increase the number of very dark leaf color forms of A. dressleri in cultivation.

Shown above, two select clones of the author’s very limited summer 2020 release, Anthurium Carib Queen™, a unique A. dressleri primary hybrid. These photos are unflashed and show plants at different stages of development. Blue highlights in this hybrid series tend to improve markedly when plants are grown in deep shade and as the plants mature from seedling stage. Plant shown left with 6”/15 cm leaf, plant on right with a 16”/40 cm leaf in late November 2020.

Mature example of an excellent clone of Anthurium radicans x dressleri bred by the author in the early 2000s, shown in his Guatemalan collection. This plant bears no resemblance to plants being sold under this name in Indonesia and elsewhere. Compare to another clone from the same cross shown in the article on pebbled leaf anthuriums elsewhere on this website. Author’s image.

A beautiful portrait of a very dark clone of Anthurium sp. nov. aff. dressleri in tropical rainforest understory, Panamá. This currently undescribed species has long been confused with A. dressleri but differs in several key leaf and inflorescence characters. Image: F. Muller.

Shown above, two exceptional, mature examples of hybrids that I made in Guatemala between 2005 and 2008 that achieve large sizes. Left, Anthurium luxurians x dressleri ‘Black Magic’™ and right, a new leaf on A. regale x dressleri ‘Voodoo Child’™. Both plants shown are being grown in California. Dark violet or blackish leaf colors require, constant warmth, shady growing conditions and careful attention to nutrition to express themselves to their fullest. Select, wild-origin A. dressleri clones (such as ‘#3’) were used to create these hybrids. The image on the right shows just exactly how dark the leaves on both this species and this apparently undescribed sibling taxon can be in nature; replicating these colors in captivity requires experimentation with lighting and micronutrition (esp. sulphur and iron) until all the tweaks work out and desired appearance is achieved.

Above, Anthurium PanaMama™, a name that I’ve used internally for several years covering A. dressleri x papillilaminum and the reverse cross that I’ve tinkered with over that time. First made in 1986 by Thomas Croat (TC 782) using an A. dressleri collected by James Folsom and Richard Cirino’s #8 clone of A. papillilaminum of cultivated origin (still alive at the Missouri BG as of 2019). The original Croat cross is reportedly a starting point for some orphan Australian hybrids, undoubtedly of complex origin due to pale-colored primary veins. Uniformly dark saturated, very velvety leaf blades and darks veins are a hallmark of primary hybrids between these two species. While offspring from hybridization of these two Panamanian endemics are generally attractive (and rare), the combination of parents I used in 2018 left me a bit dissatisfied with the results shown here. Recent work I have done with a series of alternate parent options appear extremely promising and will see commercial release in late 2021. Other images shown online purporting to be this or the reverse hybrid appear to be misnamed–intentionally or not–and evidence one or more hybrid parents in their genetic makeups.

Long confused with Anthurium dressleri, A. kunayalense Croat & Vannini is a central Panamanian rainforest endemic that I discovered and co-described in 2010 that - based on petiole, leaf and inflorescence morphology - now appears to be the westernmost outlier of the Colombian A. splendidum-luxurians-debile-giraldoi-nutibarense species complex. Fred Muller has recently discovered that it apparently hybridizes on occasion with A. sp. nov. aff. dressleri where they occur in sympatry. Note lateritic, very iron rich red clay substrate which is commonly associated with some terrestrial anthurium species in the lowland rainforests of Panamá and Colombia. Mature individuals of this species can have both subvelute and pebbled-textured leaves.

Large, fruiting Anthurium sp. nov. “Darkest Panamá” (aka, A. “Black Velvet Panama” and A. “antolakii” Vannini & Croat [ined.]) in habitat. Image ©F. Muller 2019.

Anthurium sp. nov. “Darkest Panamá”

This very surprising recent discovery hails from an undisclosed locality in–well–Panamá. I have been growing it for almost two years now from a small amount of live material that I was given for comparative purposes. Based on my field and greenhouse experience with this and other regional origin velvets, I believe that it warrants closer scrutiny to determine its relationships within the genus.

I had previously refrained from sharing images and other background information on this very beautiful aroid to third parties prior to formal determination of its taxonomic status. However, the dissemination of photos of this plant both in nature and cultivation on social media, together with commercial offerings of living plants made during spring 2021, clearly makes it fair game for all now. Pointed questions many serious aroid collectors around the world have posed to me about its validity since it first appeared on Fakebook also prompted my decision to include it here despite its (for now at least) extreme rarity in captivity.

For what should be obvious reasons, I will not provide any hints as to its exact geographic origin, provide any sort of plant description, diagnostic characters, nor cultivation guidelines for it here. I will let the images now posted online and the person who discovered it speak for themselves. In my opinion it is very likely a previously overlooked Anthurium taxon that is most closely related to the well-known Panamanian endemic, A. papillilaminum (see opening shot of that species in nature at the top of the article). When I was first shown images of this plant in the field my initial conclusion was that it represented a slightly variant new population of Anthurium sp. nov. Darién (also compare with image of that species shown above). Subsequent examination of live material grown from a pair of small stem cuts, together with side-by-side comparison of these and other related species from the region indicates that, while superficially very similar, they are indeed all quite distinct from one another in key details.

Above left, newly-emerged leaf on a young Anthurium sp. nov. “Darkest Panamá. Right, another young plant showing some of the very desirable characteristics that this taxon exhibits as it matures. This individual is the pollen parent used to create the primary hybrid shown below. Author’s plants and images.