Aquarium Fish and Invertebrates: Is there space for a global standard in commerce? Part II - Conservation

by Peter Rockstroh

A beautifully designed, high volume living reef tank in private hands, complete with state-of-the-art filtration, wave simulation and advanced LED ramp lighting for exhibit of a large variety of captive propagated Indo Pacific stony corals. Image: J. Vannini.

The global aquarium trade is one of the hobby-driven industries that managed to grow even during the year of COVID. People still like keeping tropical fish. Aquariums have had a passionate following since the mid-1800s and, except for interruptions caused by the two World Wars, this has grown steadily ever since. The technology to maintain artificial aquatic systems, both freshwater and marine, has both improved and become much less expensive. Lowering the entry cost has made the hobby more accessible to increasing numbers of individuals around the world, and so it has grown in all of its dimensions. More people have more aquariums. In the U.S. alone, an estimated 15 million people have aquariums in their homes and about one-sixth of these are saltwater tanks (Springer, 2018)

For people monitoring the pet trade, it is impossible to ignore this industry’s numbers. Today it generates USD 12.00 B in global gross sales, out of which USD 5.00 B are estimated to be fish and invertebrates. The U.S. contributes slightly over USD 41.00 MM of aquacultured fish to this market, of which roughly one-sixth are again tropical marine ornamentals (Groover et al., 2019).

Based solely on the biomass harvested from wild aquatic systems destined to be sold to hobbyists as described in Part I of this article, at first glance wild extraction of tropical fish does not seem to be a particularly high impact activity. But some of the current collecting methods, the disturbance they cause, and the extraction processes themselves can be of much higher impact than that of the harvested biomass per se. They can leave scars on delicate ecosystems that persist for a very long time (Maduppa et al., 2018).

Every activity that exploits wildlife resources and hopes to do so in a sustainable manner going forward must carefully evaluate the negative impact it causes and what has to be done to make it or keep it sustainable. If the damage done by this point has pushed target populations to the verge of collapse, the popular admonition is that we must restore balance. Translation: The affected populations must have time to recover, and the area where they occur must be protected to avoid further losses. This approach implies restricting harvest for as long as it takes to rebuild a population comparable to that at the time the extractive process started. Ideally this should be done by protecting more area than was initially under pressure to allow a repopulation that is as genetically diverse as possible. There are many advocates in favor of restoring populations with captive-bred material, but this choice must be carefully evaluated because the issue is far more complex than good-hearted intentions can imagine. I will elaborate on that subject in more detail later in this article. What is clear is that to commercially harvest many ornamental aquatic animals in a more sustainable manner will require protecting new areas and limiting catch for some species on a seasonal basis.

In 2005, the United States imported 1,802 different species of marine ornamental fish with a unit value between less than USD 1.00 and USD 20,000.00 each. The total import figure exceeded 11 million individuals, of which 52% belonged to 20 species (Rhyne et al., 2012). The amazing diversity of marine creatures that make up the saltwater aquarium hobby reflect both market demand as well as the conservation priorities. Despite recent advances in captive breeding marine fish and mariculture/aquaculture in general, the hobby is still far from being able to produce 1,800 species in captivity. The question then is this: Does the market really require this much diversity in terms of offerings?

Wild-collected, imported scarlet or Pacific cleaner shrimp (Lysmata amboinensis) are among the most popular crustaceans for tropical marine community tanks housing other inoffensive animals. This species has proven challenging to reproduce in captivity but is fortunately both wide-ranging and abundant in nature. Image: J. Vannini.

To dramatically reduce pressures on both coral reefs and reef fish, the first steps should focus on the species that make up the bulk of exports of marine fish and invertebrates. Interestingly enough, today it is possible to produce almost all of the Top 20 species of fish that make up over half of the bulk of imports.

During a poll conducted among >300 tropical saltwater aquarists worldwide (Murray & Watson, 2014) an interesting series of data were revealed concerning the drivers and preferences of this group. Although clients purchased more than 1,800 species of fish and over 500 species of marine invertebrates (Rhyne et al., 2012), Murray & Watson’s (2014) analysis of the main criteria to stock a living reef aquarium were decisions based on compatibility with current stock, aesthetics, source, and ease of care. While there are certainly trends in concept and aquarium layout, mainly oriented towards a colorful tropical reef or a small-scale biotope reproduction, saltwater aquarium hobbyists seem to pay more attention to the “social” values of their reef community. During the same poll it was established that 97% of all customers interviewed would rather purchase captive bred specimens over wild-collected, even if prices were 20% to 50% higher than what they were then paying for wild-caught animals (Editor’s note: During a series of visits to several San Francisco, California area specialty aquarium stores made in early 2021 it was evident that some informed buyers of rare tropical reef fish there were willing to pay 3-4X prices for sustainably harvested–i.e. hand netted/slurp gun captured–or hatchery bred and raised tropical marines over those offered locally for fresh imports of uncertain collection backgrounds).

The specialty market for freshwater aquarists continues to grow, particularly advanced planted tanks (biotope and naturalistic aquariums) and their nano versions. Among freshwater aquarium hobbyists there are breeders specialized in particular groups, families or genera that will set up tanks for individual species and search specifically for exceptional examples of them. This is particularly noticeable among aquarists that breed dwarf cichlids (Cichlidae), Corydoras catfish and killifish (Nothobranchiidae, Cyprinodontidae and others), among others. Another growing group of aquarists with species specific requests are those involved in competitive biotope aquascaping. Although this may sound like a very arcane, specific niche it has a large enough following to be noticeable in today’s market, not only by the demand for fish but also in an increase in the requests for select aquatic botanicals and biotope décor.

Reasonable Goals

Reviewing the availability lists of today’s successful saltwater ornamental breeders and matching them with the Top 20 species in trade, it is evident that the industry is technically very close to meeting the market demands. A market gap analysis for the Top 20 species compared breeding success per species with market demand and assigned a stoplight color to each species (Murray & Watson, 2014). Green indicated low demand covered by successful mariculture and aquaculture, Amber included species of medium demand and limited aquaculture, and Red covered species of high demand and poor current aquacultural results.

In some areas subject to overcollection in the past, common clown fish (Amphiprion ocellaris) populations are now slowly recovering, starting at greater depths. A few sites between Borneo and the Philippines still show diminished populations of both these fish and carpet anemones (Stichodachtylidae) since these invertebrates were also removed to meet demand for living reef aquariums in northern countries in the 1990s and early 2000s. Author’s image in nature.

With only three Red and three Amber species, the first goal should focus on producing those ca. 6 million fish in order to reduce pressure on their wild populations, many of which have been severely depleted for several decades now. Recent studies have shown that specific collecting sites that have received a lot of industry pressure over the past decades are already displaying a reduction of genetic diversity in proportion to population density, as in the case of the common clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) in parts of Indonesia (Madduppa et al., 2018). Tragically, commercial collecting pressures generated by “Finding Nemo” have led to not finding him at all at some sites where common clownfish were once abundant.

Parallel to these efforts, fishermen involved in collecting for this market segment ideally should be trained and involved in local maricultured production of these species in order to compensate for the reduction in wild caught fish, as well as changing the mindset of people accustomed to unregulated resource extraction rather than harvesting on a sustainable basis. Ideally, once the industry is capable of meeting the demand for any given fish or invertebrate species from artificially propagated sources, further wild collection should be restricted to occasional small numbers destined for breeding operations in an effort to maintain needed genetic diversity in captive stocks.

The second goal should be fostering the breeding efforts of farms, hatcheries and individuals to reproduce the next group of species for the trade, and gradually substitute more wild caught material with captive bred animals. As shown in the recent examples of two mariculture entrepreneurs, one in Bali, one in Panamá, the list of species bred in captivity can grow surprisingly fast as larger numbers of skilled aquaculture technicians crack the code to breed certain species, genera or families (Van Beijnen & Yan, 2020).

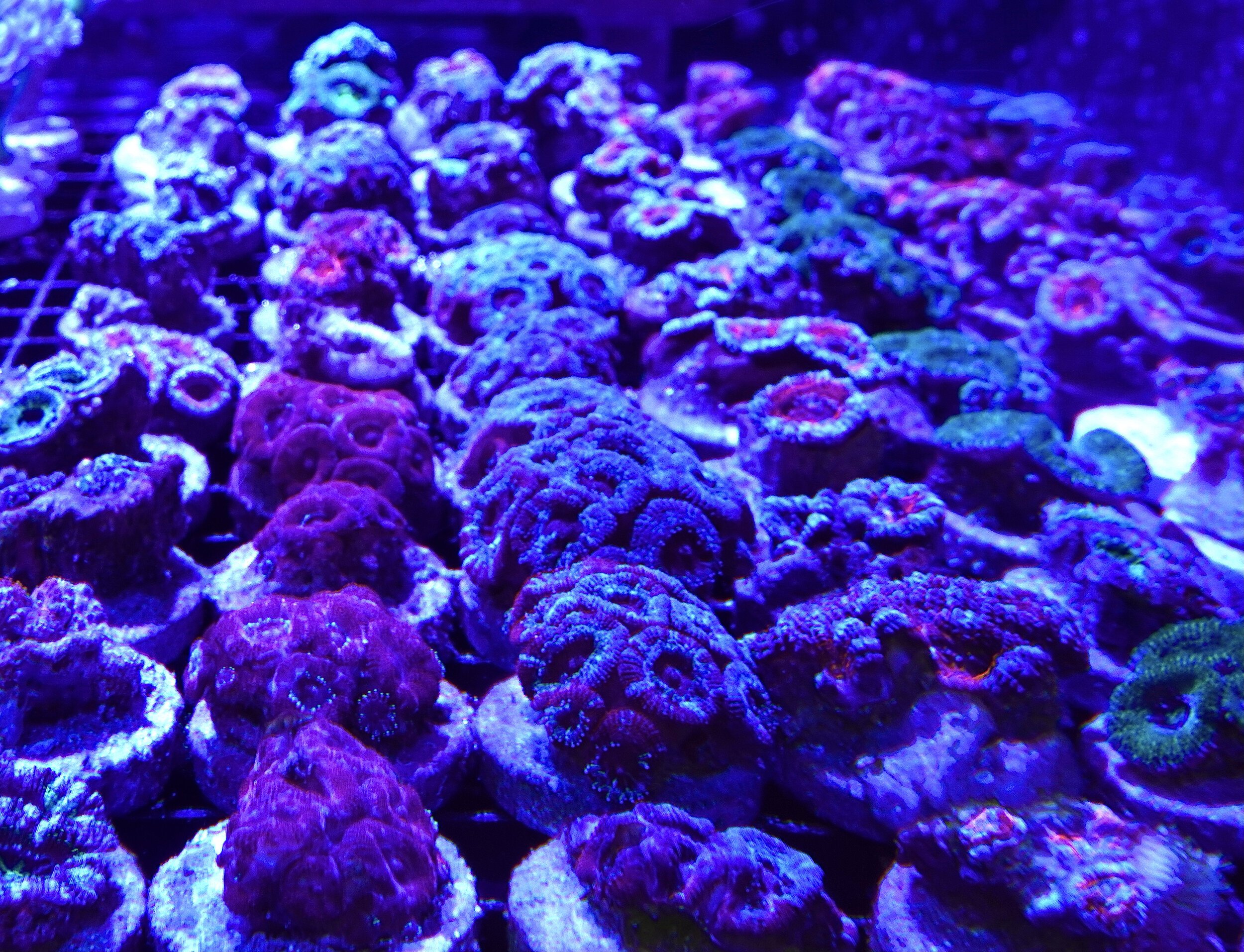

Shown above, a surreal-looking selection of blue spectrum LED illuminated, artificially propagated stony corals offered for sale in a very well-appointed saltwater aquarium store in California. The market for both origin-country maricultured and domestically aquacultured live corals has exploded over the past two decades, together with the popularity of tropical marine living reef aquaria. Successful long-term live coral culture is among the most challenging subjects for advanced aquarists, but nonetheless is increasingly popular with tropical marine enthusiasts around the world. Images: J. Vannini.

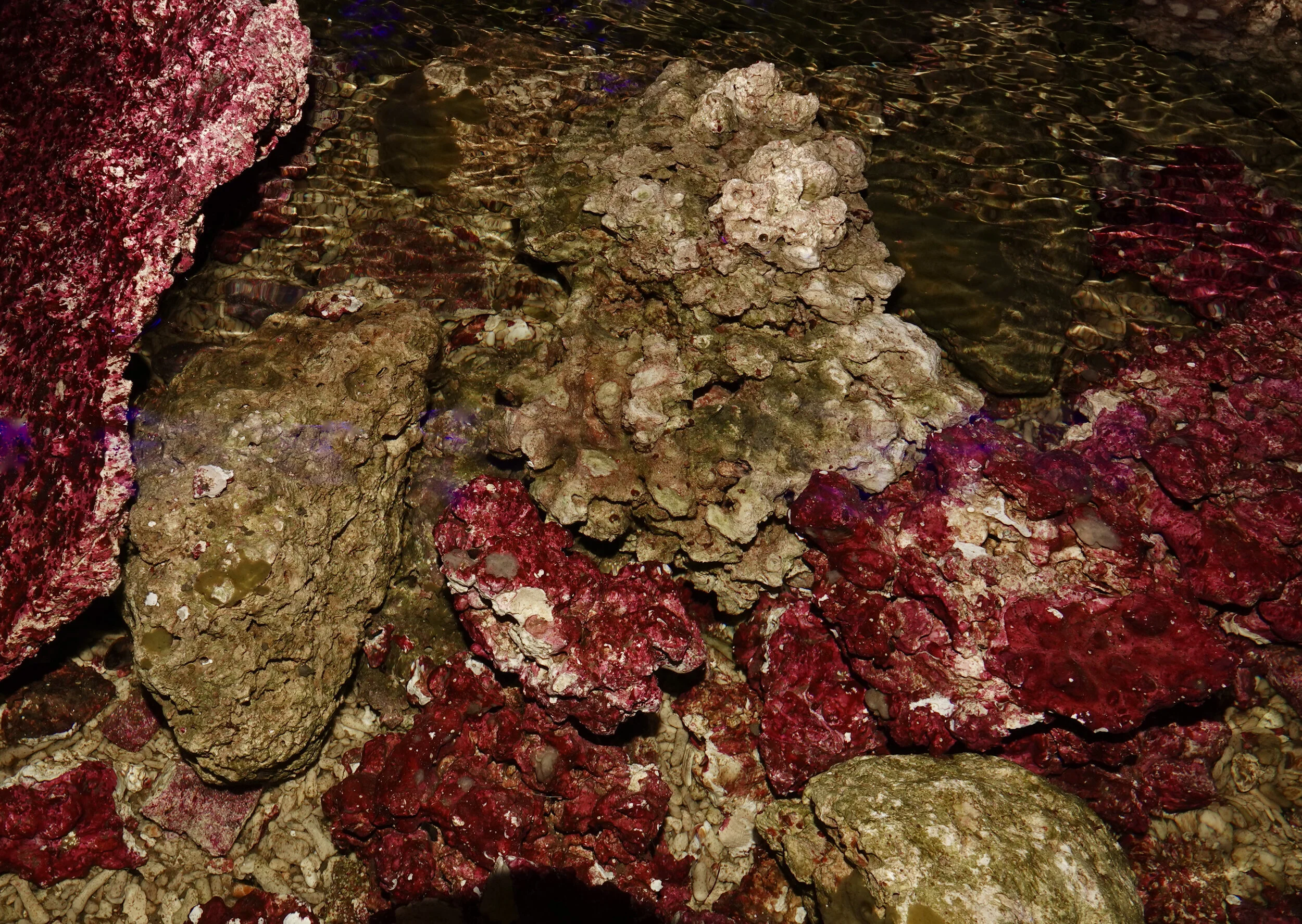

A selection of (expensive) Indo Pacific origin live rock held in a very high volume, undertank saltwater sump filter, viewed from above. Image: J. Vannini.

The ability to produce hybrids and boutique color morphs of clown fish (Amphiprion species) and other tropical marines, adds a series of interesting alternatives to the palette of reef fish for clients who choose their fish based on aesthetics and compatibility. These hybrids and select color variants also contribute to segment of the market for clients that shop for fish based on price and rarity. Today, both “designer” and other tank bred clown fish outnumber wild varieties on the market and provide clients with an opportunity to purchase specimens of a unique beauty, without touching wild populations. A Florida based high-tech tropical marine hatchery, Oceans, Reefs & Aquariums (ORA), currently offers more than 30 designer clownfish types. These hybrids and pattern mutations are also often much easier to keep than some extremely rare species of the same genus still being collected from nature.

Less extraction pressure can also occur as market tastes change. The second decade of this millennium saw a dramatic drop in so-called living rock and live sand exports; the first by 75% (2,000,000 lb/910,000 kg to 500,000/227,000 kg), and the latter by 90% (500,000 lbs/227,000 kg to 45,000 lb/20,000 kg). These reductions can be attributed to the hobby’s current preference for domestically maricultured live rock, a huge increase in the offer of very realistic artificial reef rock, dramatically higher international air cargo rates, and new filtration and lighting technology that–together with improved husbandry–promote healthy stony and soft coral growth without the need for imported living rock (Rhyne & Tlusty, 2012; Vannini, pers. comm.). This decline in imports has also contributed to reduce marginal pressures on tropical reefs across the western Pacific and Caribbean.

At this stage, freshwater aquarium hobbyists are in this sense more advanced than their marine colleagues when it comes to breeding fish. Of the ca. 5,300 species of freshwater fish currently in the trade, about 1,000 species are regularly sold. Much as is the case in marine ornamental fish, in freshwater half the sales volume is generated with just 30 species. The big difference is that there are thousands of freshwater fish breeders worldwide integrated in the industry and supplying the market with a large diversity of specialties (Evers, Pinnegar & Taylor, 2019). Although 90% of all freshwater fish (measured as individuals) are captive bred, the market still consumes a very large number of wild caught fish (ca. 90 million individuals of >4,000 species). Freshwater aquariums are a business segment whose stability is backed by a steadily increasing number of followers (ca. 14% growth annually) together with strong new trends within the hobby.

As captive bred material gradually substitutes wild caught fish, marketing efforts should also slowly shift and target a different audience. From a conservation standpoint, the industry should strive towards meeting the demand of beginners, intermediate and advanced hobbyists primarily through offers of captive bred stock, and target sales of wild-caught fish to the small segment of advanced private specialists, ex-situ aquaculturists and public aquariums.

Both tropical fresh and saltwater fish traders should eliminate the hard to impossible-to-keep species from their lists, as well as species that grow too large for a home aquarium unless the buyer has a tank, pond or pool as required for the species he will purchase at mature size. Despite the noble efforts of big fish rescue centers (e.g., Ohio Fish Rescue, Kentucky Fish & Tank Rescue), fish should not be imported to be bought as impulse purchases as juveniles only to be discarded as young adults, especially in the nearest handy body of water. When domestic pet owners abandon unwanted cats or dogs to a life on the streets, an indignant reaction by the public is the normal and correct response. It should also be the same with oversized trophy tropical fish tossed into local reservoirs.

For a long time the concept of invasive fish was automatically associated with freshwater species. Sometime during the 1980’s it is now believed that aquarium enthusiasts in Florida released a few red lionfish (Pterois volitans) offshore. With abundant prey, no predators and an amazing reproductive rate, it only took this species 40 years to invade the entire Caribbean. Many organizations throughout the region have now formed groups that dedicate a lot of time and effort to rid regional reefs of this super predator. Nonetheless, this animal always seems to be a step ahead with new surprises. It was recently discovered that they are not only freshwater tolerant, but can also swim upriver and feed on native freshwater fish. Image: Michael Gäbler 2014/Creative Commons 3.0.

Based on a risk analysis of accidental or purposeful introductions, certain species should be excluded from the trade completely. Although blanket bans are always met with strong opposition from those who consider themselves part of the responsible segment of hobbyists, some fish species ALWAYS manage to elude rules and regulations and end up wreaking havoc on local fish populations. Shark catfish such as Pangasius species are one of these evildoers, as well as many Plecostomus catfish. Excluding them from the aquarium trade might elicit a strong response from the aquarium hobbyists community; banning their imports might prompt an equally strong response from the aquaculture community. Everybody wishes for his arguments to be the most convincing, and I am reminded of a saying which I believe describes the situation perfectly: “If wishes were fishes, we’d all have ponds.”

Hopefully no ponds for these two fish groups. EVER!

In-situ Conservation

The textbook description of a species involves a series of genetic, morphological, geographic and ecological characteristics that define and distinguish one taxon from another. A species is also the sum of all niches occupied in its original ecosystem, meaning that beyond its distinguishing looks and adaptations, it is also defined by its interactions with its environment. This means that although each species can be recognized outside its native habitat, thanks to its species-defining characteristics it cannot fulfil its original role outside the original environment.

Captive-breeding ornamental fish, that is to say the ex-situ production of any given species, can increase the breeding stock of said species. To shift those efforts from preservation to conservation, it requires for these captive-bred animals be able to return to its native habitat and successfully establish a sustainable breeding population.

The difficulties posed by this ambitious goal require careful consideration before taking the plunge.

Aquarium enthusiasts take justifiable pride in their succesful captive-breeding efforts that for some species date back more than a century. For many species it takes a lot of research, creative tinkering and good luck to be able to offer the conditions and circumstances to breed them in an aquarium. When these circumstances can be reliably repeated with the same results, the method can be turned into a breeding program. If this program can be combined with a the establishment of a protected area within the species’ original distribution where the animals can theoretically be reintroduced, journalists love to describe these stories as saving a species from extinction.

Now before we pop the cork off that bottle of bubbly…

Thanks to the combined efforts of skilled private sector aquarists around the world, some very rare species or even those believed extinct in the wild still survive in sizeable numbers in captivity. What is under-represented are the efforts to protect areas where fish could be reintroduced, and the evaluation of captive bred stock to make sure that the animals have the broadest possible genetic variation and behavioral characteristics to allow for a successful establishment of viable populations.

There must be a clear distinction between introduction and re-introduction: While reintroduction is the relocation of captive bred stock into areas of its original distribution from where it has disappeared or is near extirpation; introduction refers to establishing captive bred populations in an area they had not been present before. Most of the infamous examples of animal translocations belong to the latter group.

Although reintroductions have never generated the horror stories of introductions (e.g., cane toads in Australia, cats to New Zealand and Mauritius, mongooses to tropical islands, brown rats everywhere), they must take into account a series of risk factors, especially the accidental introduction of exotic diseases carried into native ecosystems by captive bred animals.

Captive bred fish populations tend to suffer from inbreeding depression since, in the vast majority of cases, they originated from relatively small gene pools. Captive produced animals also tend to show “aquarium behavior patterns” such as naive initial responses to predators and competitors that may prove lethal back home. Successful captive breeding programs of fish species that are extinct or nearly extinct in the wild seem to evoke a feeling of complacency among conservationists and may reduce their efforts to preserve critical habitat, since they are often comforted by the thought of a large captive bred population held ex-situ.

If a species has completely disappeared from the area it is intended to be reintroduced to, the area should be researched to evaluate the changes it has undergone during the species’ absence. Key environmental factors could be different or diminished, reducing the chance of survival for the introduced populations. Since there are no established protocols for reintroduction of many fish species, high losses of the reintroduced animals are to be expected due to factors listed previously.

Zoos and public aquariums were long thought of as tomorrow’s Ark; benign, climate controlled safe havens for the world’s threatened wildlife managed by omniscient, skilled technicians that are a secure store for imperiled genetic resources. Unfortunately, the main goal of zoos and public aquaria that participate in breeding projects today is rarely the production of captive bred stock for reintroduction, but is rather focused on the environmental education component, together with (invariably) the need to raise funds for their pet in-house programs. Contrary to popular belief, zoos, natural history museums and public aquariums have contributed very little to improve breeding, management techniques or reintroduction programs for endangered wildlife, despite good intentions and some of them certainly employing very knowledgeable/skilled personnel as well as housing very valuable genetic material.

The main bottleneck for the successfully reintroduction and establishment of viable populations of endangered species is finding suitable habitat. Depending on the date and author, amphibians and freshwater fish compete for the unfortunate title of the most threatened group of vertebrates. Both groups have mostly had very little attention when it comes to protecting their original habitat ouside of some isolated areas in northern countries together with a small number of noteworthy efforts in the tropics. Fortunately, relatively small areas can harbor a very large diversity of both groups. Unfortunately, there aren’t many efforts to propose areas for the specific conservation of these taxa, at least in the New World tropics.

Many countries have established Red Lists for endangered animal and plant groups. These lists are useful tools and starting points to select possible areas to be protected, as they normally include the distribution maps of all species in that category. Protected areas focusing on fish should be defined as soon as possible, based on the range required by the different species of a community over a period of one to two years to include their seasonal migrations, so the protected areas will cover their whole life cycle.

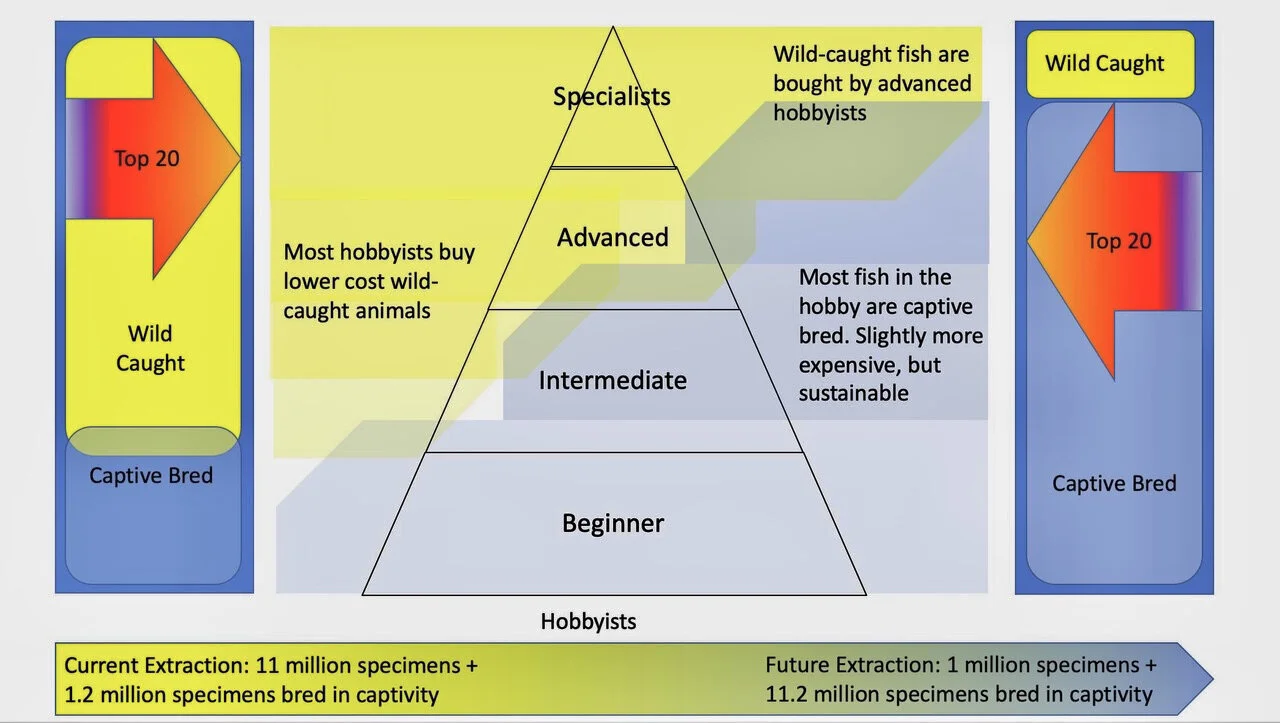

Above: Current trade of ornamental reef fish, from origin to final client. The left column shows actual origin and distribution of the catch, while the right column proposes a sustainable alternative. The pyramid represents four levels of the hobbyist market and how they are sourced today (left), and how they could be sourced in a more sustainable manner (right).

This diagram illustrates a suggested model for the market transformation of the ornamental tropical fish trade. With today’s advances in mariculture and aquaculture, the first goal is the gradual substitution of the top 20 fish from wild-caught to farmed. This step, which today is technically possible, could reduce the pressure on coral reefs and reef fish by 50%. Further research with other groups of fish should strive towards captive breeding programs to increase the number of species from the top 50 group, in order to reduce pressure on reefs to a minimum. Part of the logic behind these efforts is the fact that extremely rare, delicate, or unusual species of reef-fish should be restricted, their capture reduced to a minimum and their sales restricted to researchers and specialists. These species should never form part of wholesale or retail stocks. The model that I propose is to match real supply and demand, which in this case implies a relatively small number of specialties for a relatively small group of specialists.

A relatively normal-looking young flowerhorn cichlid (Amphilophus complex hybrid) in a holding tank. These often grotesque-looking but very popular freshwater fish are potentially invasive in parts of Central America with high native cichlid diversity that include the hybrid’s parent and grandparent taxa. They should never be released into a natural body of water anywhere. Image: J. Vannini.

No conservation efforts make any sense without the protection of the species in its native habitat. Regardless of the level of precision with which the proper biotope was duplicated in the aquarium; say with sticks and stones imported from the Amazon, if the animal disappears from nature because its habitat disappeared from the map, that species will become the biological equivalent of a flowerhorn cichlid (Amphilophus complex hybrids), living unicorns that don’t exist in the wild.

Above: Like many other top notch diving destinations Pulau Sipadan, an oceanic island off northeast Borneo, is well known for its amazing aquatic biodiversity. This soccer-field sized coral column rises from the depths of the Sulawesi Sea, combining spectacular coral gardens and large numbers of big pelagic fish species. Until shortly before establishing several dive operations on it and a few nearby islands, this was a favorite collecting spot for the aquarium trade. Today, the constant presence of recreational dive groups in the region has completely eliminated live collection activity in the area. Author’s images.

Fortunately, conservation and management of freshwater ecosystems is a field that can not only draw from centuries of experience in wetlands restoration as well as safeguarding Blue Ribbon trout and salmon runs in northern countries, but also incorporates a long trajectory of management guidelines from marine protected areas. The long overdue establishment of additional protected areas for threatened fresh and salt water ecosystems to help ensure the sustainability of fish populations for the aquarium hobby should be a responsibility shared by both hobbyists around the world and conservation agencies in the countries where these species are sourced.

Until these tracts of land and water can be identified, inventoried and managed in every country that has lost parts of its endemic fish populations but still retains prime original habitat, they cannot be considered viable conservation projects. It is imperative that the global natural resource conservation community starts focusing on the need to set aside tropical freshwater and marine reserves for this purpose and, where necessary, start releasing carefully-screened captive bred stock into these areas to restore the local fish community to give a real purpose to decades of dedicated captive breeding programs by both private aquarists and government agencies.

References Cited

Dey, V. K. 2016. The Global Trade in Ornamental Fish. INFOFISH International [Internet]. [cited 2018 June 9]. p. 55-55. Available from: http//: www.infofish.org.

Evers H. G., J.K. Pinnegar & Taylor, M.I. 2019. Where are they all from? – sources and sustainability in the ornamental freshwater fish trade. J Fish Biol. 2019;94: 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13930

Groover, E.M., M. DiMaggio & E. J. Cassiano. 2019.Overview of Commonly Cultured Marine Ornamental Fish. FA224. University of Florida.

Madduppa, H. H., J. Timm and Kochzius, M. 2018. Reduced Genetic Diversity in the Clown Anemonefish Amphiprion ocellaris in Exploited Reefs of Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:80. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00080

Murray, J.M. & G. J. Watson. 2014. A Critical Assessment of Marine Aquarist Biodiversity Data and Commercial Aquaculture: Identifying Gaps in Culture Initiatives to Inform Local Fisheries Managers. PLoS ONE 9(9): e105982. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105982

Rhyne, A. L., & M. F. Tlusty. 2012. Trends in the marine aquarium trade: the influence of global economics and technology. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 5(2):99-102.

Rhyne, A. L., M. F. Tlusty, P. J. Schofield, L. Kaufman, J. A. Morris Jr. & A.W. Bruckner. 2012. Revealing the Appetite of the Marine Aquarium Fish Trade: The Volume and Biodiversity of Fish Imported into the United States. PLoS ONE 7(5): e35808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035808

Springer, J. 2018. The 2017-2018 APPA National Pet Owners Survey Debut. 2017-2018 APPA National Pet Owners Survey ©By the American Pet Products Association, Inc.

Van Beijnen, J. & G. Yan. 2020. Culturing marine ornamentals: a $5 billion opportunityhttps://thefishsite.com/articles/culturing-marine-ornamentals-a-5-billion-opportunity

Rhyne, A. L. & M. F. Tlusty. 2012. Trends in the marine aquarium trade: the influence of global economics and technology. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 5(2):99-102.

Welz, A. 2018. Basement Preservationists: Can Hobbyists Save Rare Fish from Extinction? Yale Environment 360, Yale School of the Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/features/basement-preservationists-can-hobbyists-save-rare-fish-from-extinction