Lycaste virginalis - from wet nurse to white nun

by Jay Vannini

The white nun orchid, Lycaste virginalis f. alba. Author’s collection.

Among the most celebrated Neotropical orchids is Guatemala’s national flower, Lycaste virginalis f. alba. Known in the region as “La Monja Blanca” (the white nun) this albino form of a usually pink-flowered species is a no-holds-barred, spectacular bloom in life. While flowers on all the white forms are maddeningly delicate when handled and bruise very easily, they are certainly worth the effort involved in growing them to perfection. Healthy flowers have excellent substance, crystalline texture and can last up to six weeks in good condition if keep cool, bright and dry (pink forms last notably longer than albas). The common Spanish name, “monja” in Mesoamerica derives from the resemblance of the floral column to a tiny, white-clad nun in prayer and dates from at least the late 18th century.

Click on images to open in an expanded lightbox or to view footnotes.

Above left, lip and column detail on a cultivated Lycaste virginalis f. bicolor in the author’s collection in California and right, the same details on a wild Lycaste guatemalensis (Image F. Muller).

This beautiful species caused great excitement when it was introduced into ornamental horticulture in Europe 180 years ago, particularly as collectors became aware of the amazing variety of flower color forms available in imported wild plants. The high esteem with which Lycaste virginalis was held by 19th century English horticulturalists is evident in an observation written in The Gardener’s Chronicle in the late 1800s that it (as L. skinneri), “…seemed about to have as great a future as the tulip”. Frederick Boyle, in an article on cool-growing orchids in Longman’s Magazine (1889), refers to its common name among growers at the time, the “Drawing-Room Flower” due to its hardiness as a mostly winter-flowering plant, ease of cultivation by amateurs, and that common forms were “cheap”. Hundreds of thousands of flowering-sized plants were collected from the cloud forests of central Guatemala and exported to Europe where all ultimately perished due to losses in transit, improper cultivation, the fact that they were in collections abandoned or destroyed during wars or were lost amidst the subsequent economic depressions of the early 20th century.

Lycaste virginalis f. virginalis flowering in the author’s home.

Lycaste is largely a Mesoamerican genus, with 33 accepted species and a dozen or so named wild hybrids (see paragraph lower down for examples involving L. virginalis). This number includes the yellow-flowered species that have been segregated into the somewhat contentious genus Selbyana by Archila in 2010. Guatemala and Costa Rica are the two countries housing the greatest number of species, with the Verapaz Departments of Guatemala being particularly rich in Lycaste diversity, reporting 14 recognized species and several natural hybrids (also including the yellow-flowered taxa).

Lycaste virginalis is usually a robust orchid when mature, epiphytic in nature, with well-developed dark green pseudobulbs between 3-4”/7.5-10 cm tall and handsome, 18-24”/45-60 cm twin plicate leaves. Most flowers of this species display very pale pink sepal shades, with the most commonly observed forms having slightly darker petals, and a pink and white mottled lip with a pale-yellow callus (f. virginalis). Exceptionally dark-flowered examples (ff. rosea, roseo-purpurea, and nigrorubra) are deep pink or pale plum-colored, often with pencil stripes on the sepals and petals and with reddish-violet lips. During the 19th century many color forms of this species were described as varieties but have now been shown to be just variations on the themes outlined herein. Despite many contrary assertions published online this species is non-fragrant. Some of the better-known older names - generally listed as varieties but now properly considered forms - for non-alba flower color combinations include: armeniaca (whitish or pale apricot sepals and petals with an orange lip), delicatissima (sepals white blushed with pink, petals darker pink, a white lip finely spotted with pink and a yellow callus), purpurea and superba (rose pink sepals with darker petals, pure white lips with red-spotted side lobes and yellow calli), rosea (saturated rose sepals and petals with purple veins with a white-spotted deep crimson lip), nigrorubra (sepals mauve, petals plum-colored with a reddish-purple to violet lip and yellow callus), and roseo-purpurea (sepals and petals mauve, lip and callus magenta). These appellations are based on the original 19th century varietal descriptions published for the forms in horticulture and will not necessarily match images or descriptions shown on the internet.

The images shown here should give growers a better idea of what the better-defined color forms look like in life. When attempting to match the 19th century descriptions to both wild and cultivated flowers today, besides obvious color characters overall, growers should also take particular note of lip and callus color.

Three good examples are shown above of the very uniformly-colored Lycaste virginalis f. delicatissima in cultivation: left, line bred, ex-Japan, growers Alek Koomanoff and Golden Gate Orchids; middle, line-bred ex-U.S. source in author’s collection(Images: ©J. Vannini); right, wild-origin Guatemalan in private collection there (Image: ©F. Muller). Note the vivid yellow calli and white flash marks on the petal tips of all three plants,

A very large-flowered, line-bred Lycaste virginalis f. alba in the author’s collection. This plant can produce flowers in excess of 7.5”/19 cm across lateral sepals. Minor blemishes evident on sepals two weeks after the flower opened in a well-lit living room.

In the Seventh Edition of Benjamin Williams monumental “The Orchid-Growers Manual” (1894), there are 16 distinct forms of this plant listed as varieties, together with their respective footnoted color and black and white illustration references from Reichenbachia, Lindenia, Warner, etc. While many of these forms persist in cultivation today, they are often shown under different/incorrect names. An intriguing observation made in this book is that many of the descriptions of flowers on cultivated examples of wild-collected plants emphasize ~7”/17.5 cm flower spans which, while by no means the largest recorded size, would be considered exceptional for flowers of this species in cultivation today. The largest flower that I have bloomed – a domestically-produced line-bred f. alba – spans >7.75”/19 cm across the 2.4”/6 cm wide sepals. The most impressive flower that I have personally examined was an outstanding, near mauve-flowered wild-collected plant exhibited at a small lodge near La Unión Barrios, Baja Verapaz in the late 1980s and was just over 8”/20 cm wide.

There are also examples of older awarded plants measuring over 8”/20 cm wide. These exceptional clones make L. virginalis the largest flowered species in the genus, although its western Colombian relative, L. schilleriana are, on average, wider than most run-of-the-mill L. virginalis.

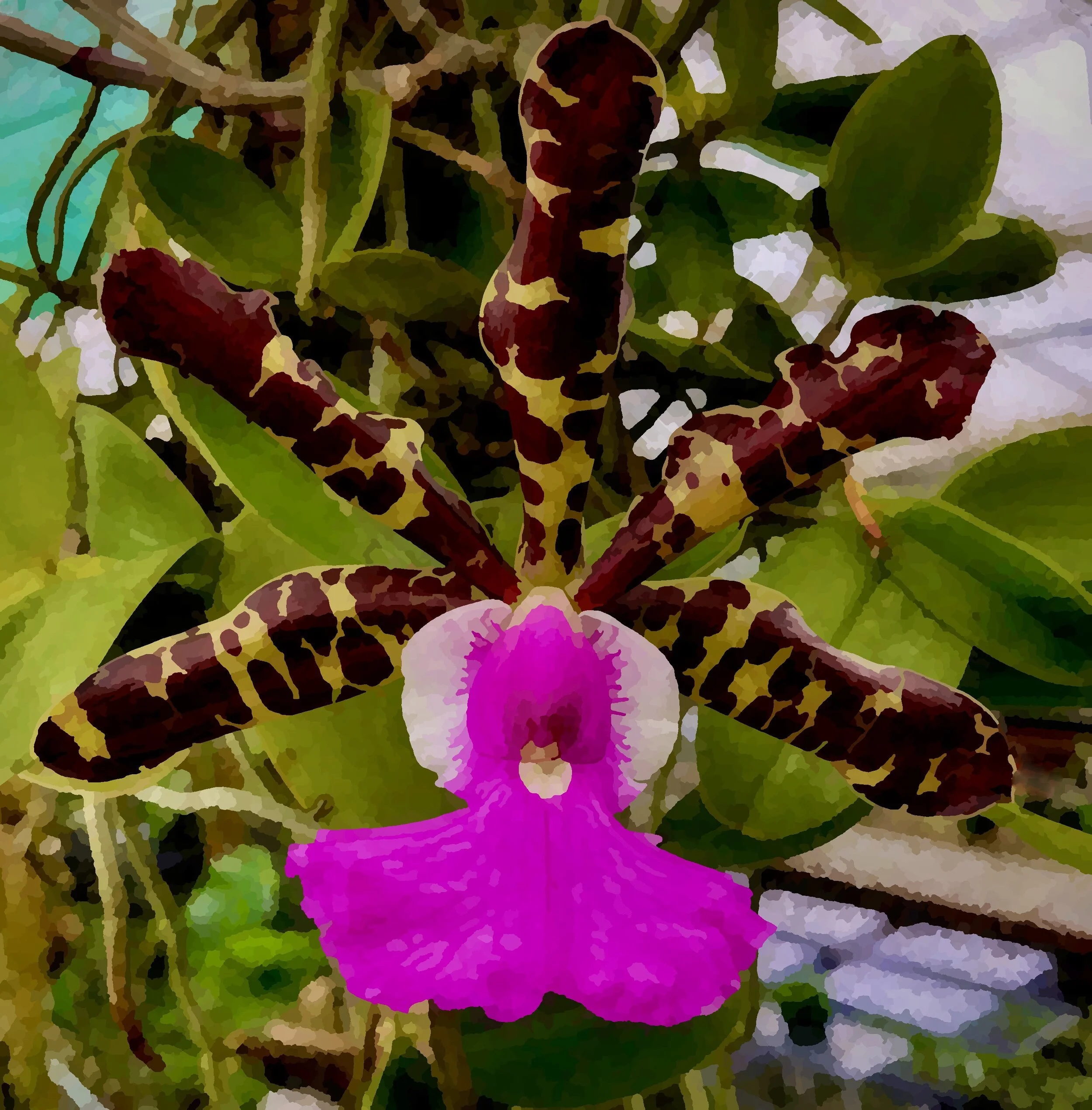

Brightly-colored clone (probable hybrid) from batch of line-bred Hawaiian Lycaste virginalis in the author’s collection. Henry Oakeley described var. labelloflava in 2008 based on a plant of similar origin.

Fowlie’s “The Genus Lycaste” (1970) provides an annotated list of 13 nineteenth-century “varieties” of L. virginalis that were published together with colored plates and 21 “varieties” published with descriptions but no image provided by the authors. He also provides his own artist’s watercolor renderings of the flowers of 10 of the “varieties” that he recognized, including delicatissima, roseo-pupurea, vestalis, purpurata, picturata, hellemmensis, purpurea, bicolor, candida, and alba.

Oakeley (2008) conjured up three rather unremarkable “varieties”, albaviridis, labelloalba and labelloflava (hybrid?) from old Wyld Court Orchids Nursery material (Berkshire, England, closed early 1980s), that have been discarded either because they lacked a preserved type specimen or failed to find their way into usage.

Archila and Chiron (2011) segregated Lycaste virginalis with pure white flowers and no yellow visible on the lip, callus or column as f. cobanensis. This form is exceptionally rare today and the name is not yet in wide use among growers. While I am inclined to agree with the notion that true albino flowers lacking all visible pigments throughout warrant their own name (i.e. cobanensis), strictly speaking they are just pure white subforms of f. alba. There are other variations of white-flowered plants showing varying degrees of yellow-tinged labella or calli, but among albas f. cobanensis is the most desirable and least frequently encountered.

Two fairly large-flowered examples of Lycaste virginalis f. cobanensis in cultivation in California. The plant of the left is grown by Alek Koomanoff and Golden Gate Orchids; plant on the right is in the author’s collection. Both are from U.S. line breeding of f. alba. This fully albino form is considered a very rare subset of L. virginalis f. alba by most growers and specialists.

Flowers of this species are usually about 4.25-5”/11-12.5 cm wide with 1.25”/3 cm wide sepals. As mentioned above, exceptional examples have flowers >7-8”/17-20 cm in diameter with 2.25-2.75”/5.6-7 cm wide sepals. As is the case for many orchids, breeders strive for large, flat flowers in profile with clear colors and wide, unreflexed sepals with no furling on the margins. Lateral sepals may stand out at right angles or be down swept to a greater or lesser degree. In my opinion, any round, “flat” flowers with clear, bright colors and sepals 1.5”/4 cm or wider are keepers. Despite many available color plate references from the 19th century that provide a visual guidelines as to what fine examples of these flowers look like, there are a surprisingly large number of images in both recent literature (e.g. Oakeley 1993; Beutelspacher and Moreno Molina 2018) and on the internet of mediocre quality Lycaste virginalis/skinneri and L. guatemalensis.

L. virginalis (as skinneri) var. purpurea by Alphonse Goossens in “Lindenia” 1893. This form shares most key floral characters with f. superba but is rosier-colored overall.

This species is known to hybridize in nature in Guatemala with several other indigenous lycastes and closely-related genera, including with Lycaste deppei (= L. x smeeana), L. lassioglossa (L. x lucianiana), and L./Selbyana cruenta (L./Licobyana x imschootiana). All these hybrids have been remade in cultivation, generally yielding better quality flowers than the wild hybrids. It has been hypothesized that the wide variability evident in flower form and color in wild L. virginalis is the product of gene flow from other sympatric lycastes and that there are hybrid swarms evident and prevalent in parts of its historical range.

A very well-flowered Lycaste Lucianana-dominated hybrid. Grower, Golden Gate Orchids.

The documented distribution of Lycaste virginalis extended from the northwestern Chiapan highlands to the Lagunas de Montebello region, the extreme southeastern Sierra Madre de Chiapas through much of the broadleaf cloud forests of central and western Guatemala, into the uplands of western Honduras at least to Cerro Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara Department.

Lycaste guatemalensis flowering in cloud forest, Volcán Ipala, Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller).

Spring and summer-flowering southeastern Guatemalan, extreme southwestern Honduran and northern Salvadoran populations on the Pacific versant have traditionally been lumped together with Lycaste virginalis and were once known as Ipala types (after a volcano in extreme southeastern Guatemala). This now localized and sometimes autogamous ecotype was elevated to full species status and first described as L. guatemalensis by Archila in November 1998, then again a year later. Like L. virginalis, this taxon also exhibits a variety of flower and color variants, including f. alba. Recently, plants closely resembling L. guatemalensis have been found in nature at two undisclosed locations on the Caribbean versant of Guatemala (Edgar A. Mó, pers. comm.). All these populations probably need to be critically re-evaluated as a potential subspecies or variety of L. virginalis, as conceptualized by Tinschert (1983) and Oakeley (1993).

Typical flower form of Lycaste guatemalensis flowering in nature, Volcán Ipala, Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller).

The current Mexican distribution of Lycaste virginalis is apparently restricted to protected forests near the Lagunas de Montebello in Chiapas state where it has been teetering on the verge of local extinction for many years (Soto Arena 2001; Beutelspacher and Moreno Molina 2018). In Guatemala, there are relict populations reported from climax cloud forests and their fragments in the Departments of San Marcos, Huehuetenango, Quezaltenango (still?), El Quiche, the Verapaces, El Progreso, Zacapa, and extreme southeastern Izabal (still?). While originally inhabiting lower montane rainforests from ~4,200->6,500’/1,300->2,000 m, most lightly-disturbed and climax cloud forest extant in Guatemala is now restricted to ~5,200’/1,600 m and higher.

Historical reports show that this species was abundant in the Verapaces during the late 19th century and was still regarded as “rather common” throughout the region by correspondents of Oakes Ames and Donovan Correll when they were writing “Orchids of Guatemala” in the late 1940s and early 1950s. But continued commercial pressures and deforestation around Cobán through the mid and late 20th century ultimately decimated local populations of L. virginalis. Legendary plant collector Clarence Horich’s observations and collections made of this species in nature in Alta Verapaz Department during 1962 (in Fowlie 1970) show that it was already largely extirpated near the town of Cobán by that time. Although considered “rare”, he did find it growing epiphytically in the undercanopy of high cloud forests of the upper Polochic Valley in Alta Verapaz between the village of Tactic and Cerro Xucaneb. Based on his rather limited experience in this area, he wrote that albino forms were infrequently encountered, with perhaps only one in two thousand plants (0.0005%) having white flowers. After some effort, and having reportedly seen relatively few L. virginalis in nature, he finally managed to acquire a single wild f. alba plant that had been found growing in a group of pink-flowered plants by a Q’eqchi’ Maya collector. So much for his one in 2,000 claim! Commercial exports from Guatemala are documented through nursery catalogue, auction announcements, published anecdotes and collector offerings from the mid-1800s onwards, peaking around the turn of the century, through to the 1970s by both local nurseries (especially the Pacheco’s during the 20th century) and visiting foreign plant collectors. As one example, Martien Oversluys, a commercial collector for Frederick Sanders and Co., was in Cobán on several occasions in the early and mid-1890s buying large numbers of L. virginalis from local sources for shipment to England. In a letter to Sanders in April 1895, he noted that he already had 5,000 of these plants in hand and expected to have “at least 8,000” within the following 10 days (in Ossenbach 2009). Following the opening of the paved highway from El Rancho to Cobán (CA-14) in the late 1960s, the once remote populations of this species in the eastern Sierra de Chuacús and western Sierra de las Minas in Baja Verapaz became readily accessible to collectors and wild plants were extracted by the sack load. By the mid-1970s, the continued illicit export of white-flowered forms that had been legally protected since 1946 prompted the Guatemalan government to prohibit the export of all orchids, a rule which persisted into the 1990s. In the interim, the Guatemalan government lobbied to get the alba form of L. virginalis listed on CITES Appendix I (in 1975; transferred to App. II in 1994), which complicated legal international trade in both artificially-propagated seeds and flasks. Nonetheless, it is common knowledge in Guatemala and California that foreign orchid collectors continued to travel to Guatemala seeking to acquire exceptional wild-collected clones of this species – particularly albas - throughout the 1980s and into the mid-2000s.

Three now rare, dark-pink and purple-flowered forms of Lycaste virginalis of wild origin. Left, f. rosea, La Unión Barrios, Baja Verapaz (Image ©J. Vannini); middle, close to f. nigrorubra in nature, undisclosed locality, western Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller); right, exceptional cf. f. roseo-purpurea, grown and photographed by ©Edgar Alfredo Mó, Cobán, Alta Verapaz.

Excellent flower form and color in line bred Lycaste virginalis f. alba, with just a bit too much pale yellow on the callous and column for a perfect f. cobanensis! Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids. Author’s image.

My own observations are that the typical pink-flowered forms were still locally common and conspicuous in very wet, mossy forest at some rather remote localities in Baja Verapaz from 1975 until the beginning of the 1980s when increasing deforestation had a devastating, permanent negative impact on all of Guatemala’s native flora and fauna. For obvious reasons, white-flowered forms of L. virginalis have always been extremely popular among local gardeners, plant collectors and decorators. Both national and regional orchid shows during the fall and winter usually focus on displays of large specimens of albas and other exceptional forms. During the cardamom export boom that transformed the economy of Cobán in the early 1980s, as a visiting spice buyer I saw several very large specimens of f. alba that had been gifted to local cardamom processors by Q’eqchi’ Maya farmers and middlemen (coyotes) seeking to ingratiate themselves with these individuals. In one case, a recently-collected white-flowered specimen plant was displayed in the garden of a well-known resident coffee and cardamom dealer, suspended from a large garden tree by heavy chains that supported a gigantic mass of live and dormant pseudobulbs, together with associated bark and debris that must have weighed well in excess of 100 lb/46 kg.

Lycaste virginalis flowering in canopy in nature, undisclosed location, Guatemala (Image: F. Muller).

Lycaste virginalis is now rare in the wild and difficult to observe in habitat unless one is accompanied by a knowledgeable guide. Local reports in Guatemala claim alba forms are extinct in nature. This seems both unlikely and bombastic, since not every extant locality has been surveyed for plants and genes for albinism presumably persist in all wild populations. Local collection of wild plants continues unabated whenever it is discovered by campesinos or plant collectors. Pressure is particularly persistent in forest fragments in the Verapaces where they still occur. Based on occasional press reports and comments from recent visitors, its much more accessible variety/subspecies/sibling species from southeastern Guatemala, L. guatemalensis, is also still being poached despite guards patrolling the small area where it still occurs in the country. There are small colonies of mature L. virginalis growing wild in private reserves in the Verapaz departments, the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve and elsewhere in western and central Guatemala, but they persist in numbers only where they are relatively inaccessible, or where someone concerned with their preservation can keep constant vigil.

Lycaste virginalis has three minor controversies related to its naming; the first for origins of the genus itself, the second revolving around the valid specific epithet, and the third as to the correct translation of its native name in Q’eqchi’ Maya.

Fred Muller’s weimaraner Jules standing guard over a flowering Lycaste virginalis f. virginalis growing as a terrestrial in cloud forest at an undisclosed location in central Guatemala. Image F. Muller.

The British botanist John Lindley proposed Lycaste as a carve-out of a number of plicate-leaf species previously included in Maxillaria in 1843 in Edwards’s Botanical Register (Vol. 29, Misc. 14). He did not, unfortunately, provide much of a rationale for his naming of the genus, other than “…Lycaste was a beautiful woman”. Most amateur orchid growers now attribute the name Lycaste to Helen (Helenus) of Troy’s “beautiful sister”, supposedly of that name. While Helenus did indeed have many sisters, including her equally famous twin, Cassandra, a search of her mythical father Priam’s daughters shows no “Lycaste”. The Australian orchid breeders Fred Alcorn and Michael Hallet (1993) note that a misread of the Greek spelling of one of her sisters’ names, Laodice, might conceivably be construed by one unfamiliar with written Greek as “Lycaste”. This is an error that a 19th century scholar like Lindley seems unlikely to have made, but it certainly is a possibility. Bolstering the rather weak argument in favor of a misspelled “Laodice” serving as the inspiration for the genus’ name is that she was, in fact, said to be Priam’s most beautiful daughter.

Lycaste virginalis f. alba ‘Chaste’ in profile. Author’s collection.

In Lindenia 1888 (PL. CLIII) under “Etymology” in the written description for Lycaste skinneri var. alba, it is again noted that it is, “…the name of a Greek girl renowned for her beauty”.

Alcorn suggests another plausible source for the name. In the Classical poem “Dionysiaca”, the lascivious Greek God Dionysos (= the Romans’ Bacchus) was said to have been accompanied into battle by raging, crazed nymphs (the maenads) that had been his wet nurses (!), including “the silverfoot/charming Lycaste”. Alcorn notes that the while Nonnos, the Roman poet who penned “Dionysiaca” around 500 CE is a very obscure author today, educators of the mid-19th century would probably have been familiar with the material. Although John Lindley did not attend university himself due to his modest background and economic constraints, he did lecture extensively beginning in his late 20s and was appointed Chair of the Department of Botany at University College London in 1829, at the age of 30. His many publications and biographical notes show him to be very intelligent, well-read and held in high regard by the botanical authorities of his day. This reference would probably have been known to him.

Then there is yet another possibility that explains Lindley’s “fanciful name”. Cited in John Lempriere’s well-known “Bibliotheca Classica; Containing a Copious Account of all the Proper Names mentioned in Ancient Authors”, Lycaste was also the name of “a harlot… of great beauty” or a “woman of great beauty” of Sicily. She enamored Butes the Argonaut and bore him a son, Eryx. As a demigod king and a boxer, Eryx had a famous run-in with Heracles that didn’t quite work out to his benefit. Lempriere’s reference work has been in constant circulation since its first publication in 1788 (it has something like a dozen editions available including recent reprints) and has been a handy and well-known annotated checklist to source obscure names in writings from Antiquity ever since.

While we may never know the true origin of the name, it seems obvious that the naming of genus Lycaste has its origins in Greek mythology, and that the best evidence suggests that it derives either from the god Dionysos’ “charming” wet nurse, Lycaste, or Eryx’s beautiful concubine mother, Lycaste.

Lycaste guatemalensis flowering in nature, Volcán Ipala, Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller).

As to the debate surrounding the species’ name…in 2011 Guatemalan naturalist Fredy Archila and French botanist Guy Chiron provided a long, very detailed explanation of their rationale for resurrecting Lycaste virginalis from synonymy. This combination had, in fact, been in general use by orchid growers and botanists from the early years of the 20th century into the late 1960s when Jack Fowlie, et. al reinstated L. skinneri in an article in “Orchid Digest” (Vol. 30, No.7), which he later defended in his monograph on Lycaste in 1970. Rather ironically given subsequent events, in an expanded second description of L. guatemalensis in 1999, Fredy Archila chided local orchid enthusiast Otto Tinschert for the incorrect usage of the “synonym” L. virginalis, instead of L. skinneri, in typifying southeastern Guatemalan plants. My personal view is that further work with this taxon will prove that Otto Tinschert was generally correct in his conceptalization of this ecotype and that Archila was not.

Without venturing too much farther out into the weeds with this subject, a brief summary of the naming chronology is provided below.

Lycaste virginalis was originally described by James Bateman as Maxillaria skinneri in Edwards’s Botanical Register in 1840 (Vol. 26), based on dried flowers that he received from Guatemala from the famous commercial plant collector, George Ure Skinner.

It was subsequently described as Maxillaria virginalis by Michael Schweidweiler in 1842 from material collected in 1840 by Jean Linden in San Bartolo, Chiapas, Mexico in the Bulletin de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles-lettres de Bruxelles ((9)1:25). Plants had flowered for the first time in cultivation the year earlier in both an English stovehouse and during a flower show held at the botanical garden in Brussels, Belgium.

Also, in 1842 but this time based on living material from Guatemala, James Bateman re-described the species in the Edwards’s Botanical Register (Vol. 28), again as Maxillaria skinneri. When John Lindley renamed this species as Lycaste skinneri in 1843, he based his description on the second Bateman holotype, partially because Bateman had erroneously decided that his 1840 description was not based on a pink-flowered species as he intended (in fact, it was) but rather on L./Selbyana cruenta. Due to nomenclatural rules that invalidate the names of taxa described twice under the same epithet based on different type accessions, Maxillaria (Lycaste) skinneri became an illegitimate “orphan” in search of a valid name. Fortunately, Schweidweiler’s option was available, hence the proposal Lycaste virginalis (Schweidw.) Linden (1888).

In spite of the compelling evidence presented in the Archila and Chiron paper and the current acceptance of Lycaste virginalis as the valid binomial by Kew’s, Plants of the World Online (POWO), the naming controversy rages on as only the most trivial arguments can in the orchid world.

Lycaste virginalis, young plant flowering in cloud forest undercanopy, undisclosed locality in Guatemala (Image: F. ©Muller).

With regard to its correct Q’eqchi’ Maya name and the published confusion regarding its translation, Edgar Alfredo Mó, a native Cobán son, orchid researcher and fluent Q’eqchi’ speaker writes (free translation, notes mine): “…white nun orchids have been called “Saq Ixq” by some, which translates as Saq = white and Ixq = woman, or “white woman”. We don’t say it like this, we say, “Saq Hix”, which means Saq = white and Hix = jaguar or ocelot, so “white jaguar”. The association derives from the spots on these animals (and many orchids - JV). When we want to refer to an orchid we say “Hix”, pronounced “Jish” (Spanish) or “Heesh” (English - JV). If you were to ask me how to say “orchid” in Q’eqchi’, I would tell you that the word we use is “Hix”.

Cultural biases have clearly influenced local names. Pious Catholic Spanish and Criollo narrators of the 18th century imagined a nun, dressed in white and hunched in prayer, in the flower’s interior while naturalist Q’eqchi’ Maya observers simply saw the white form of a normally varicolored orchid flower.

A very good winter flowering Lycaste virginalis f. alba ‘Chaste’. Author’s collection and image.

My first experience with Lycaste virginalis f. alba was at the 1975 national orchid show in Guatemala City. As a centerpiece, a tower of spot-lit, beautifully-grown specimens met visitors amidst a forest of foliage and flowers at mezzanine level at the INFOM building in Zona 9. Although I had already observed a few pink-flowered plants in nature and for sale at stands along the road from Salamá to Cobán, I had never seen any alba forms. I was greatly impressed by this amazing collection of large wild-collected Monjas Blancas. While orchid culture in country has greatly improved in the intervening decades, I never again saw a display of f. alba at a show in Guatemala anywhere near as good as those well-grown specimens exhibited by the founding members of the AGO. During my time in the country I did not grow this species on a permanent basis but did keep a few average quality L. guatemalensis in my collection. Several of my friends also have/had good to excellent collections of L. virginalis and L. guatemalensis, both wild-collected and artificially-propagated, particularly Otto Tinschert (d. 2006), Walter del Pinal (d. 2015), Silvia and Mario Palmieri, and Edgar Alfredo Mó.

Lycaste guatemalensis, wide-sepal form flowering in nature, Volcán Ipala, Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller).

Among older generation Guatemalan and American growers, the memory of Don Otto Tinschert is very closely associated with his work breeding and promoting Guatemalan native orchids. Together with Moises Behar and Banco del Cafe, S.A. he published the widely admired, “Guatemala y Sus Orquideas” in 1998. Although Otto had several benches filled with excellent quality Lycaste virginalis, L. guatemalensis and their natural hybrids in his collection in the hills outside of Guatemala City, he admitted to me on several occasions in the late-1990s that he had difficulties maintaining f. alba over the long term. I suspect that his very hard well water was behind his problems growing them consistently. Despite this, he did breed and produce many flasks of the alba form to drive the point home to Guatemalan conservation authorities that local orchid breeders could potentially produce hundreds of thousands of plantlets from seed to reduce pressure on wild populations if export regulations were relaxed. He was one of the first people to conclude that the white and pink-flowered lycastes from Volcán Ipala, in Jutiapa Department and elsewhere in southeastern Guatemalan cloud forests (at the time) were phenotypically and morphologically different from L. virginalis from the Caribbean versant and warranted varietal status. He summarized some of his initial conclusions in an article for the American Orchid Society Bulletin in 1983, including the correctly interpreted but stylistically flawed description of the late spring and early summer-blooming L. virginalis, Type Ipala mentioned previously. This was later published on three separate occasions as a standalone species, L. guatemalensis (Archila 1998-1999).

Lycaste virginalis ‘Don Otto Tinschert’ flowering in California. Author’s plant and image.

I own a division of a very beautiful Otto Tinschert-sourced Lycaste virginalis clone imported to California by an anonymous collector back in the day and that was acquired by me as a single large, dormant bulb in early 2012. Some AOS judges visiting Guatemala for orchid shows occasionally received select, wild-origin L. virginalis and L. guatemalensis clones from both Otto Tinschert and Otto Mittelstaedt (d. 2000) as a door prize for showing up, which partially explains their presence in California. I know that Otto Tinschert also gifted and swapped plants with many of his friends and colleagues in Guatemala and elsewhere (including me), but especially with orchid growers in Cobán, so unfortunately, I have no clue as to its original provenance. To my eye it looks like it is a L. virginalis f. delicatissima outcrossed to L. lasioglossa, L. x lucianana or some variation of this theme and may be a good example of the “hybrid swarm” plants from the Verapaces mentioned earlier. Archila (in CONCYT 2011) erroneously identified a very similar-flowered wild form from Alta Verapaz as L. balliae, correctly a name for the artificial hybrid between cultivated L. plana (= L. measuresiana or L. macrophylla) and L.virginalis made by Sanders and Co. in 1896. Certainly, it is vigorous when conditions are to its liking. It has 6”/15 cm wide colorful flowers with narrow sepals, very large pseudobulbs (to 4.75”/12 cm) and long, wide leaves. It is very floriferous and spectacular in bloom, but thus far usually skips years to generate a mass flower event every 24 months, usually in late January and February.

Flowering specimen of Lycaste virginalis ‘Don Otto Tinschert’ in the author’s collection. This plant produced almost two dozen flowers from two pseudobulbs, with most visible in this image.

Lycaste macrophylla ‘Machu Picchu’. This species has been crossed with L. virginalis on many occasions to produce hybrids with saturated red colors. Growers: Alek Koomanoff and Golden Gate Orchids. Compare with image of L. macrophylla var. litensis shown at the end of this article.

My observations through 2015 are that the very best classic forms appear to be rather rare in cultivation in Guatemala, especially the intense pinks and purples (ff. rosea and others) that were commonly observed at plant sellers in La Unión Barrios and Purulhá, Baja Verapaz and Cobán, Alta Verapaz through the 1980s. Recent images of plants at the Cobán, Alta Verapaz show (December 2017 and December 2018) posted online on social media show many plants with very substandard-looking flower form and poor vigor. The original Mittelstaedt collection at Vivero Verapaz near Cobán, that once housed many thousands of examples of this species, has been high-graded so thoroughly that very few good-quality plants were left when I last went through about a decade ago. Emilio Cahuec (d. 2016) of Purulhá, Baja Verapaz also had a large collection of mediocre to fairly good quality clones of Lycaste virginalis that he grew and propagated for local sale, exposed on wooden and bamboo benches in treefern pots under semi-natural conditions at his home. It is widely believed by some US breeders that almost all older lycastes in cultivation in Guatemala are virused due to poor cultivation practices. Fowlie’s claims notwithstanding, lycastes are now known to be vulnerable to Cymbidium Mosaic Virus (CymMV) and other similar pathogens, so growers should make an effort not to spread it through their collections. My own experience in country suggests that careful plant sanitation (esp. sterilization of cutting tools between plants) is not a major priority for many local (or U.S. for that matter) growers and that most large L. virginalis in cultivation there tend to decline over time. That said, some quite exceptional and very well-grown clones do persist in private Guatemalan collections, including some in and around Cobán and Guatemala City. Wild-collected plants that continue to enter cultivation every year also yield individuals with exceptional flower quality now and again. Attempts at propagating this species for sale from PTC and seed by nurseries in México, in an effort to reduce collecting pressures on wild plants in eastern Chiapas, are ongoing.

A very good example of seed-grown Lycaste virginalis f. superba, first flowering. Author’s collection. The cross of two select pink-flowered forms that produced this plant also generated a surprisingly high percentage of fine f. alba.

Currently, so-so quality white-flowered forms appear to be marginally easier to find for sale in the U.S. than pinks, probably due to residual inventory overhang from the old Orchid Zone f. alba breeding program. Despite having looked assiduously for exceptional quality, very dark pink-flowered forms in the ‘States, I have not seen a good one for sale online or at an orchid show over the past eight years. Anyone reading this in the U.S. who has a clean division of one for sale or trade, please contact me via the email address provided at the end of the site.

Line bred, putative Lycaste virginalis, ex-Japan, growers Alek Koomanof and Golden Gate Orchids.

Ironically, as native germplasm has dwindled some Guatemalan orchid growers have opted to import Lycaste virginalis and its hybrids from nurseries in Ecuador, California and elsewhere. It is a sad fact that there is wide consensus among lycaste collectors and breeders that almost all the finest examples of this species are now grown outside its native range in Guatemala, Honduras and Chiapas, Mexico. Due to the supply and demand dynamic prevailing in country, at this time, high-quality L. virginalis f. alba clones available in Guatemala are typically valued at many multiples of prices asked for comparable plants in the U.S.

A pair of very beautifully-flowered Lycaste Highland Peak ‘Cooksbridge’. Grower, Golden Gate Orchids.

Older complex hybrids such as the white forms of Lycaste Koolena (=L. Auburn x L. virginalis, Giles 1967), and L. Shoalhaven (L. Koolena x L. virginalis, Apperly 1976) as well as a few white and pink-flowered L. Chita crosses can occasionally bear a strong resemblance to the true species, so caveat emptor. This is particularly true when these have been further back-crossed to L. virginalis. I generally find that one giveaway are very long peduncles that often stand well free of the foliage, coupled with oddly-shaped pure yellow lips and columns and “pinched” sepals. Outsized, very round and cupped flowers on a plant labeled L. virginalis are normally evidence of mistaken identity. Still, some carefully-selected white-flowered hybrids with a lot of L. virginalis in their backgrounds can often be extremely difficult to separate from unadulterated L. virginalis (as are some wild hybrids) so always source plants carefully from reputable suppliers who are known to have significant collections of these plants, with provenance.

A seed-grown plant from a Hawaiian line bred release of Lycaste virginalis f. alba showing evidence of hybrid ancestry. Author’s collection and image.

Suitable media for Lycaste virginalis include shredded treefern fiber, on its own or mixed with bark and charcoal, sphagnum moss and traditional composted conifer bark mixes blended with charcoal, perlite and small amounts very coarse sphagnum peat moss. I grow all of mine in pure New Zealand sphagnum moss in vented plastic baskets but have the advantage of having access of large volumes of fairly pure water to work with. If I were growing elsewhere, I would probably use shredded treefern fiber, Orchiata bark and charcoal, both medium sized, at a 2:2:1 ratio. I am currently experimenting with growing a young flowering-sized plant as a mount on a suspended cork plaque, which is only feasible in an airy, high humidity environment such as a cool greenhouse or in and around Cobán.

First bloom opening on a four year-old, seed-grown Lycaste virginalis f. alba on a fall evening in the author’s kitchen bay window.

In my experience, this species resents being overpotted even more than most other orchids. Plants in too large pots seem very prone to sudden decline and plants grown thus will often drop their leaves at the onset of flowering. While underpotted plants are somewhat unwieldy when in flower due to their being top heavy, it is far better to seek a solution for adequate display (e.g. tying up leaves, staking, double-potting) than one from having to deal with rotting pseudobulbs. Preferably, “pot on” with as little disturbance to live roots as possible, as opposed to aggressive repotting that involves major root pruning. Unfortunately, many cultivated plants in hobbyists’ hands in Guatemala are grossly over-potted in the vain hope they will grow large in these containers; this is a recipe for disaster over the long-term.

Flowers will generally be flatter, larger and more intensely-colored when grown under cool, bright conditions as opposed to shade.

This species is prone to unsightly leaf spotting when kept too shady and/or poorly-ventilated. Broad-spectrum systemic fungicides suitable for orchids can help to suppress fungal issues. Improved cultural conditions work even better!

I find these plants to be heavy feeders when growing, and good flower numbers are only achieved with a consistent and well thought-out fertilization regimen.

Pure water, gentle ventilation, cool nights! These are three enormous advantages when considering growing this species. I have found this species to tolerate seasonal exposure to fairly high summer temperatures (85-90 F/29-32 C) as long as overnight lows drop into the low to mid-60s F (16-18 C). This is not a good orchid selection for collections in the lowland tropics and subtropical areas with consistently warm summer nights.

Following hot summers in the San Francisco Bay Area, my plants (numbering about 35 clones) will begin flowering in late September, peak in January and February and continue in flower through the end of March or late April. Under normal climate conditions blooms will begin opening much later in the fall or early winter, peak in mid-February and finish flowering by early March. Lycaste guatemalensis flowers from late May through July in nature in Guatemala but throughout the spring and summer in California and elsewhere in the northern hemisphere. Established, well-cultivated large plants tend to flower most heavily every other year and it seems tricky (for some of us at least) to reliably coax large numbers of inflorescences from individual pseudobulbs on an annual basis.

A very nice pink, line-bred Lycaste virginalis with yellow highlights on its mid-lip. Shown in mid-April in California and more than one month into flowering. Several siblings of this clone had very vivid yellow markings on the labellum and also flowered well into early spring. This batch of plants is characterized by its very long-lasting pastel pink flowers. Author’s collection.

Flowers MUST be kept cool and dry or they will spot rapidly. I reduce watering frequency on my plants during the winter, but probably not as much as other growers recommend. Cleary’s (thiophanate-methyl) mixed with distilled water (no surfactant) and sprayed while flowers are budded will provide some measure of protection from Botrytis cinerea fungal spotting in high humidity environments. In nature, this species flowers during the coolest, windiest, driest time of the year and even in cloud forest relative humidity in the breezy undercanopy is much lower than it is for the rest of the year.

Slugs seem to prefer new tender growths to flowers but will by no means ignore a particularly prized bloom. Otto Tinschert used tufts of surgical cotton wrapped halfway up stems to protect valuable flowers. Molluscicides of your preference are useful to have around. Aphids will also attack flower buds in the late fall.

I favor vented pots and baskets to let their long, wiry roots wander. Treefern pots, while quaint and suitable for growing some ferns and gesneriads, are a terrible option for many orchids over the long-term. They are still a mainstay for many Lycaste growers in Guatemala, particularly those located in the Verapaces, and many show plants are presented in these pots. I have seen many fine plants grown in clay pots, both in Guatemala and California, and keep a few specimen-sized plants in clay bowls myself.

Above left, commercial quality plants of Lycaste virginalis f. alba for sale by the Orchid Zone at the Pacific Orchid Expo 2014. Right, Lycaste virginalis f. alba ‘Golden Gate’ HCC/AOS. Grower, Golden Gate Orchids.

California-based nurseries and breeders that have traditionally offered improved Lycaste virginalis include Cal-Orchids, Santa Barbara Orchid Estate, Marni Turkel and the Orchid Zone (f. alba). Orchids Limited in Minnesota occasionally offers select L. virginalis forms from both domestic and Japanese sources. Recently, some of these nurseries have closed doors or drastically limited their offerings of the species, but there seems to be a small renaissance of interest in L. virginalis, particularly among EU and California growers, so hope springs eternal that all of the most showy forms will return to horticulture.

A particularly nice example of the red-flowered form of the northwestern Ecuadorean Lycaste macrophylla var. litensis in the author’s collection. This is a fall-flowering variety, unlike the mostly spring flowering northern populations. This species influence on darker-colored modern hybrids like those shown above is obvious.

Two large-flowered complex hybrids from Japan derived from Lycaste virginalis and L. macrophylla. Left, Lycaste Abou Rits 3n x 2 n. Right, Lycaste Abou First Spring ‘Will’. Growers, Alek Koomanoff and Golden Gate Orchids.

Japanese, Australian, Hawaiian and Taiwanese nurseries can produce very good plants, mostly complex hybrids based largely on Lycaste virginalis, but also some very nice select forms of the species. Goshima Orchids, Hideki Nagai, Green Valley Orchids and (formerly) Abou Orchids are all Asian nurseries whose names are associated with high-quality lycastes. These plants are sold as houseplants in some flower markets in Japan, finally providing them with a mass market that has so far eluded them in the west.

While Lycaste virginalis will never be as ubiquitous as tulips, they more than make up for their commercial shortcomings with their amazing flowers and convoluted but romantic backstory.

Seed-grown Lycaste virginalis f. bicolor, first flowering. Author’s collection and image.

I would like to express special thanks to Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids and Alek Koomanoff, Member Emeritus of the SF Orchid Society, for generously sharing their considerable experience successfully growing, propagating and judging these plants in the SF Bay Area. Both have also provided me with very valuable live material for my personal collection in California. Thanks also to the very thoughtful feedback and outstanding images taken in habitat and cultivation provided by Fred Muller, as well as for invaluable information regarding the current status of this species in central and southeastern Guatemala and the Chiapan border area. Edgar Alfredo Mó of Cobán, Alta Verapaz has also been very gracious in providing an image of one of his superb plants in cultivation, as well as insights into the correct local name for this species in Q’eqchi’.

Lycaste guatemalensis colony in flower, late spring, Volcán Ipala, Guatemala (Image: ©F. Muller).

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2019-2025, ©Jay Vannini, and ©Fred Muller 2019.

Follow us on: